Susan Marsh asks: why is it that if a wolf preys upon a native wild ungulate, or even a domestic calf or sheep, it is called a cold-blooded killer, yet when a human hunter shoots an elk it is considered a “harvest” or when thousands of beef cows are sent to slaughterhouses little thought is given, in language, to the truth that those animals are involuntarily giving up their lives to feed humans? Photo of wolf in Yellowstone courtesy Jacob W. Frank/NPS

Sometimes all I have

are words and to write them means

they are no longer

prayers but are now animals.

Other people can hunt them.

…A tanka by Victoria Chang (from

Narrative, February 2019)

The words we use.

Lately I’ve been wondering about how carefully we choose the words we use and whether we consider the implications and hidden baggage they carry. Subtle nuances we grew up hearing stick with us for life. Sometimes they are not so subtle and stick like pins in a voodoo doll. Sometimes they live through the ages and invade our collective belief system, the way we unconsciously agree that the sky is blue.

Frederich Nietzsche wrote that “A uniformly valid and binding designation is invented for things, and this legislation of language likewise establishes the first laws of truth.” [

On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense, 1873]. We can’t speak truth without submitting to authority (the dictionary) by which we agree on the word that signifies our meaning. We say the sky is blue, but the words

sky and

blue are cultural constructions.

In the sciences, we discover truth—until we find out something new, then we cast that adjusted knowledge into stone until the next drop of understanding leaks in. The way we look at the universe is an example: we’ve gone from believing the earth was at its center—and assassinating anyone who thought otherwise—to understanding that our solar system is on the trailing edge of a small galaxy, one among zillions. We are even able to admit that there’s a lot more going on out there than we can imagine.

Yet the truth eludes us if we’re not careful, in part because of our invented language for things. Nietzsche continues in his essay with what he might call the anti-truth: “The liar is a person,” he writes, “who uses the valid designations—the words—in order to make something which is unreal appear to be real.”

Our culture is shot through with lies we agree to accept as if they were the truth. We call it obfuscation, a way of lying to ourselves and coming to believe what we say. Most of us can sniff out deception in the way government and institutions invent euphemisms to hide rather than reveal what they are really talking about. How often do we unconsciously incorporate these terms?

I consider as an example the way we speak about the natural world. By “we” I mean people of the Western tradition, influenced by the likes of Rene Descartes. He called himself rational but denied an obvious and observable truth, that other species

are sentient, intelligent, and in possession of emotions. He argued that animals lacked a soul or mind, and therefore had no emotions and could not feel pain. Unfortunately his views became prominent in Europe and North America, allowing people to treat animals as property, not other beings with whom we share this world.

How convenient. We shop for pork and beef without thinking about the suffering that brought animals to our tables. We let unwanted pets out the door and drive away. We deny any hint of kinship by referring to an animal as “it” instead of he or she.

My computer’s grammar police underlined the word whom at the end of the last paragraph. It wanted me to substitute which.

Let’s hope we’re becoming more enlightened about the status of other species as we learn how intelligent they are, from whales to ravens. On second thought, perhaps not. In Wyoming it’s still a time-honored sport to run down coyotes with snowmobiles.

Genome sequencing has placed us in the midst of the pantheon of earthly life: we share 99 percent of our genes with chimps, 90 percent with mice, and 84 percent with dogs—presumably including coyotes. A billion year old ancestral life form that gave rise to both plants and animals left us each with commonalities in our genomes. At last our rational science is helping us catch up to so-called primitive peoples and centuries-old cultures which hold that we are part of the world and all living things are our kin.

In the Western tradition we still use language to set ourselves apart, to create the illusion of superiority. Nowhere is our Cartesian reluctance to acknowledge the individuality of other life forms more prominent than in the lingo of forestry and wildlife management agencies and the land grant colleges that graduate their employees.

We don’t cut down mature lodgepole pine trees; we harvest timber. Even the tree itself is known by foresters as “standing volume” rather than a component of a complex ecosystem which provides food, shelter and oxygen to myriad species. The term ignores the complexity of the tree, an ecosystem of its own, as well as its interdependence on all that surrounds it. “Volume” refers to nothing more than the board-foot, the number of slices 12 inches square and an inch thick that are estimated in a timber stand.

I don’t argue against using lumber. We live in houses. But we treat forests like we do beef cattle, as a lifeless commodity. Private forest-product companies are at least honest about their purpose: they call their forests tree farms.

Those who create useful and beautiful things from wood, who select and cut a tree from their property or a neighbor’s and use it for an object of quality and endurance show a different attitude. Those who cut their own firewood remember and thank the tree whenever they set a log on the fire.

A researcher examines a tree in the middle of a forest to assess how much carbon dioxide it might be sequestering. While touting the vital role trees play in nature is a departure from them being valued only for their stumpage or human uses, it often falls short of recognizing their intrinsic sense of being. Recent studies have shown that trees actually possess their own kind of awareness to things happening the environment around them. It might not be on the level that humans attribute to higher sentience but it is a radical departure from the way trees have been regarded merely as objective commodities that exist to be harvested. Photo courtesy Lola Fatoyinbo/NASA

George Nakashima, famed architect, woodworker, and author of The Soul of a Tree has this to say about his work. “It is an art- and soul-satisfying adventure to walk the forests of the world, to commune with trees, to bring this living material to the work bench, ultimately to give it a second life.” This was a man who did not waste wood.

Where language is concerned wildlife fare no better than forests. Hunters don’t shoot deer or elk, they harvest them, as if the creatures of field and forest were planted like corn. Beware when you hear that we must “manage” predators: that means only one thing—kill them.

Some creatures are planted, with the express purpose of harvest. Often these are alien species that wreak havoc with the natives. Fish farms pass diseases to wild salmon and pollute the local waters. Lake trout gobble the fry of native cutthroats, robbing Yellowstone’s grizzly bears of a needed protein source in summer. Rocky Mountain goats, introduced to the Snake River Range in Wyoming for sport hunting, have increased and spread into Grand Teton National Park where native bighorn sheep are struggling to survive.

Wildlife professionals employ terms best suited to the stockyard. Most of us are thrilled to hear the first warbler of spring or the bugle of a bull elk at the end of summer. Biologists refer to these as “territorial behavior.” While accurate enough, notice how much distance between ourselves and our relatives is placed by the use of such bloodless professional diction.

We engage in fine dining while wildlife “feeds.” In my experience, wolfing down a sandwich at work while typing on the computer and answering the phone more closely resembles feeding than dining.

It’s been ten years since a citizen science effort began in our local area (

Nature Mapping Jackson Hole). I was part of the group that set protocols for data entry, and I remember a particular conversation about how to describe what the creature observed was doing. We were trying to make our data compatible with that of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department so the entire body of information could be accessed in one place.

We started out with the activity list of Game and Fish, whose focus was somewhat limited. The activity descriptors included walking, standing, running, loafing (resting), and feeding. Breeding and territorial behavior rounded out the list, and if none of these applied we could simply say the creature’s activity was undetermined.

Immediately hands went up in the meeting room. What if it’s a duck? Wouldn’t it be swimming? What if the duck is flying?

The Game and Fish activity list was intended for use in cervids, meaning elk in our corner of the state. Surprisingly, there was a fairly heated argument about whether flying and swimming could be added, since this was an established data base and we were a bunch of upstart volunteers. But we weren’t just counting elk. Our purpose was to gather observations of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. Some of them swam, some of them flew.

Reluctantly, the Game and Fish representatives agreed to consider the additions. If nothing else, we could add them to our data sheets and if they didn’t fit into the statewide one, there was always the category of undetermined. Who cared, I wondered to myself, what the animal was doing anyway? In the space of a minute a magpie could be walking, flying, feeding, and generally raising hell. Which should I choose?

The debate took another turn when someone asked, “What if the animal is playing?”

Silence. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department habitat biologist squinted as if to ask, are you serious?

The stories of encounters with wildlife began to fill the room, presented slowly and shyly at first and then with more insistence: the elk calf seen kicking up his heels and jumping in circles through a muddy slough. The fox kits chasing one another in a meadow. A raven sliding down a frosty metal roof, flying back to the ridge, and doing it again. A wolf lying on his stomach at the top of a snowy slope and with a gentle kick of his hind feet glissading to the bottom. No one mentioned otters since we all knew they did nothing but play.

The group sorted ourselves into camps: pro-play and anti-play. We’ve seen this with our own eyes, some said. How can we not record it? Couldn’t this information be useful to know under what circumstances wild creatures felt at ease enough to play?

This was foreign territory to the wildlife experts and soon the discussion ended with a resounding No. They’d already given enough ground in accepting flying and swimming, and who knew what kind of crazy activity the rest of us would come up with next? Play remained off the list.

It wasn’t a big deal, yet in a deeper sense it is. Why are we so afraid, especially those of us trained in the sciences, to acknowledge parallels between our behavior and that of other animals? In modern times our aversion to anthropomorphism is drummed into us to the point of feeling innate, but humans have always used it as a bridge between ourselves and others. Medieval renderings of the sun and moon give them human faces. Myths give animals godlike powers and human traits. These have helped us make sense of the world, at least until science shoved them all aside.

We’ve created a culture insulated from wild nature, encouraging us to stop caring that we are adrift. We speak of the land, forests, and wildlife not as aspects of home but of natural resources. We give serious consideration to colonizing the moon or even Mars rather than try to clean up the mess we’ve made of our own planet.

A shared behavior isn’t the same thing as a false attribution of human traits to others. I walk, my dog walks. Do we walk the same way? No. We each do what we do in our own way but there are many things we share, in addition to a good number of our genes, which help us relate to pets and wildlife alike. Seeing ourselves in others, whether people or other species, is the basis for empathy.

How do we unravel the words used to describe, name, tell the truth or tell lies? How do we keep a sharp ear for the subtleties of words that don’t quite hit the mark? And most of all, how do we salvage a scrap of humility as a species whose interactions with other forms of life usually place us on top? We place ourselves above other people as well, in cultures old and new. We areThe People, the chosen ones, the ones whose creed is the only true religion.

We’ve created a culture insulated from wild nature, encouraging us to stop caring that we are adrift. We speak of the land, forests, and wildlife not as aspects of home but of natural resources. We give serious consideration to colonizing the moon or even Mars rather than try to clean up the mess we’ve made of our own planet.

These are diversions, as dangerous as the euphemisms used to distance our relationship with animals and trees. Understanding what we really mean to say requires us to slow down, be more deliberate, seek to communicate and connect. To witness what is before our eyes before we open our mouths.

“If an animal does something, we call it instinct; if we do the same thing for the same reason, we call it intelligence.” – Will Cuppy

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mountain Journal congratulates Susan Marsh for being honored with the Raynes Citizen Conservation Award given by the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative at its 2019 Wildlife Symposium in Jackson Hole. The award, created in honor of naturalists Bert Raynes and his late wife, Meg, recognizes citizens who have made significant contributions to advancing public understanding and appreciation for the natural world.

Marsh, whose art is at right, shares some thoughts after receiving the Raynes Citizen Conservation Award at the 2019 Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative Wildlife Symposium in Jackson Hole. Photo by Todd Wilkinson

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/ba/6b/ba6b1209-f295-414b-a7f7-f8fc81bef30f/ertnwj.jpg)

Professor David Goodall, Australia’s Oldest Working Scientist

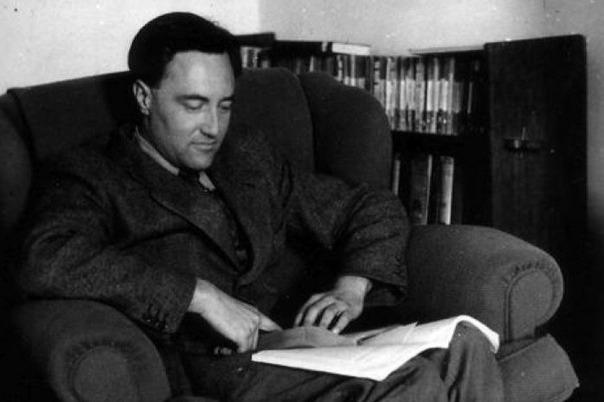

Professor David Goodall, Australia’s Oldest Working Scientist At work in the 1950s.

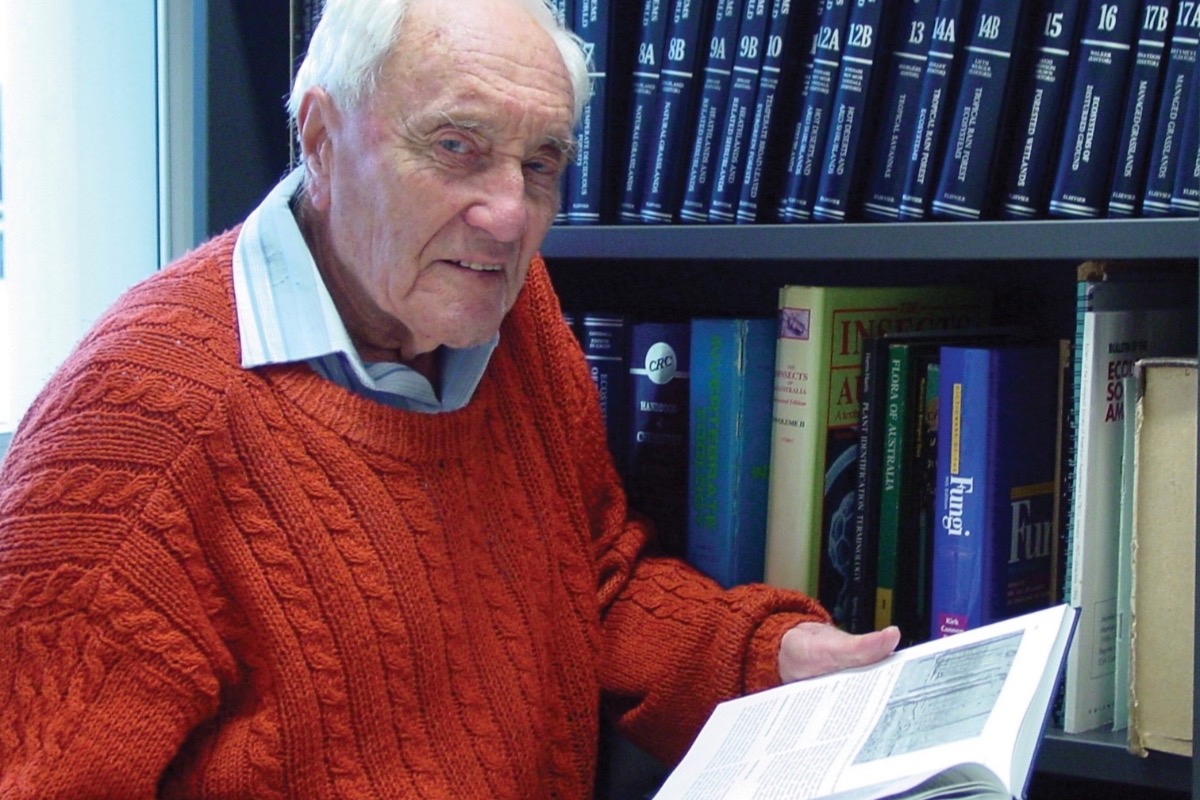

At work in the 1950s. Carol & David at an Exit workshop in 2016

Carol & David at an Exit workshop in 2016

David with his edited series: Ecosystems of the World

David with his edited series: Ecosystems of the World At 103, David travelled by gyrocopter to the remote Kimberley station (Kachana) near to Kununurra to visit the eco sustained cattle station of Chris and Jacqueline Henggeler.

At 103, David travelled by gyrocopter to the remote Kimberley station (Kachana) near to Kununurra to visit the eco sustained cattle station of Chris and Jacqueline Henggeler. At Kachana, David was back ‘in the field’ courtesy of the station’s tractor service.

At Kachana, David was back ‘in the field’ courtesy of the station’s tractor service. David on his 104th Birthday (4 April 2018, in Perth). His birthday cake was a cheesecake, his favourite.

David on his 104th Birthday (4 April 2018, in Perth). His birthday cake was a cheesecake, his favourite. David receiving his Order of Australia in 2016

David receiving his Order of Australia in 2016