Newly obtained documents show how officials pursued plans to remove protections from a beloved animal despite internal warnings about sea level rise

Jimmy Tobiasfor Type InvestigationsTue 1 Mar 2022 06.00 EST

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/mar/01/florida-key-deer-endangered-climate-extinction

When Hurricane Irma ravaged south Florida in September 2017 it inundated homes, knocked out electricity for millions and killed more than 30 people.

The devastation was not confined to humans, however.https://interactive.guim.co.uk/embed/from-tool/co-publishing/index.html?vertical=News&name-of-publication=Go%20to%20site&logo=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.gutools.co.uk%2Fimages%2F69e45a329efd0a170edb9d4902263f29038a6dc7%3Fcrop%3D0_0_858_373&bio=This%20story%20was%20produced%20in%20collaboration%20with%20Type%20Investigations.&link=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.typeinvestigations.org%2F

In the Florida Keys, one of the state’s most beloved animals also took a beating: the Key deer, a small subspecies of white-tailed deer that evolved in peaceful isolation on the islands and is now protected under the Endangered Species Act. Irma drowned them, slammed them into buildings and dragged them out to sea. “With Irma, we probably lost about 30% of the deer,” said Nova Silvy, a zoologist who has studied the deer since the 1960s on Big Pine Key, where most of them live.

Though the deer population has largely bounced back, the hurricane’s toll foreshadowed the dangerous future faced by this animal. In the coming century, the impacts of the climate crisis, especially sea level rise, will probably inundate many of the Florida Keys, including the endangered deer’s core habitat on Big Pine Key and neighboring islands.

Despite this bleak outlook, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which administers the Endangered Species Act, has been working on proposals in recent years that would strip the Key deer of its endangered species status – even as the agency’s own scientists have highlighted the threat of rising sea levels to the deer’s habitat, according to records obtained by the Guardian and Type Investigations.

These efforts began under the Trump administration, which oversaw a concerted effort to remove protections for imperiled species, and they have outraged conservationists as well as some former FWS officials, who have opposed the agency’s attempt to remove protections for the Key deer.

Advertisement

“There are things happening [to the Key deer] down there that would raise flags for any animal,” said Tom Wilmers, a retired FWS biologist who spent years working with the Key deer. “And yet the agency is in denial. I just don’t understand how delisting or downlisting that animal helps anybody.”

More broadly, however, the plight of the Key deer is a window into the Fish and Wildlife Service’s broader failure to adequately protect endangered species threatened by the climate crisis. Most notably, an obscure but consequential legal memo from 2008, signed by top interior department officials at the end of the George W Bush administration, effectively absolves the FWS and other federal agencies that decline to regulate greenhouse gas pollution that harms endangered and threatened animals under the Endangered Species Act. As the law’s leading enforcer, FWS’s inaction is especially consequential.

“We are putting out ten gigatons of carbon emissions per year, plus or minus, and those emissions are causing the planet to warm. And we know as the planet warms a lot of things are happening, from extreme weather events to waterways being ice-free for longer,” said Stuart Pimm, a professor of conservation at Duke University. “They may not be quite as direct as someone going out with a shotgun and killing a bald eagle, but they are every bit as potent a factor in causing species extinctions.”

Presidential administrations have legal latitude to rescind the memo, but neither the Obama nor Trump administrations did so. Now, a group of scientists and conservationists, including Pimm, are calling on the Biden administration to take action by empowering the FWS to better protect imperiled species – not just Key deer, but polar bears, sea turtles and more – from the climate emergency. Until the White House does so, they say, the Endangered Species Act will remain hobbled when it comes to tackling one of the biggest threats that endangered species face.

Advertisement

The Key deer was supposed to be a conservation success story. By the mid-20th century the subspecies had been hunted to near extinction, leaving only a few dozen deer left, when the federal government established a wildlife refuge around Big Pine Key and listed the animal under the Endangered Species Act. From there the little deer made a comeback, and according to surveys conducted in 2020, they now number about 750 individuals or more.

On a windy spring day on Big Pine Key, Chris Bergh, a scientist and the south Florida program manager for the Nature Conservancy, points to the desiccated grey remains of several dead trees. Bergh has studied the impact of sea level rise on the Florida Keys ecosystem for more than 15 years. The pines that once stood here, he said, have retreated as rising ocean water slowly shrinks the precious freshwater pools that sustain the island’s wildlife.

Indeed, even before the rising ocean fully drowns the Key deer’s home range, salt water contamination will ruin their drinking holes. Whether in 50 years or 100, the deer’s island habitat is probably doomed – so it would seem the deer are more in need than ever of the federal protections granted under the Endangered Species Act.

But the FWS has taken a different view. On 13 August 2019, its southeast regional director, Leo Miranda, drafted a memo to the agency’s top official at the time, “proposing to delist the Florida Key deer”.

“This determination,” he wrote, “is based on the best available scientific and commercial information, which indicates that the threats to this species have been eliminated or reduced to the point that the species no longer meets the definition of an endangered or threatened species.” He justified his proposal by citing the deer’s high population numbers and arguing that “there are uncertainties regarding what effects changes in sea-level will have on Florida Key deer habitat … before inundation” from rising waters.

Advertisement

A year earlier, though, FWS’s own scientists were already warning that sea level rise could imperil the deer’s habitat. In a draft research paper obtained by the Guardian and Type Investigations, the scientists drew on a range of existing research, including studies conducted by other federal agencies, to conclude that Key West could see between three and nine feet of sea level rise by 2100. In one set of scenarios modeled in that research, low-lying areas in south Florida like Big Pine Key would be mostly inundated between 2060 and 2080. That degree of sea level rise would wipe out the deer’s core habitat.

“The Florida Keys are going underwater due to sea level rise (SLR),” the paper’s authors wrote in an early version of the paper. “All SLR scenarios agree and depict this to happen.” The paper featured an image of what Big Pine Key could look like in the future: a tiny spit of land and a few squat mangrove trees standing above rising waters.

The draft research paper was circulated among agency staff, including Miranda, as early as August 2018. Nevertheless, FWS proceeded with its effort to remove the deer from the endangered species list until late summer 2019, according to documents obtained by Type Investigations and the Guardian through a public records request.

“I don’t know why they would do that – start writing a delisting rule at a point in time where you have the agency staff raising concerns,” said Karimah Schoenhut, a Sierra Club attorney who works on Key deer issues. “Agency scientists were pointing out sea level rise issues, saying there is no way you can delist species.”

Advertisement

Eventually, FWS backed away from the delisting plan, after the US Geological Survey found in a report that FWS had failed to take into account research that “would suggest an even greater risk to Key deer and its habitat than included in” FWS’s assessment of the deer’s status. But the agency didn’t entirely give up. Instead, it began planning to downlist the deer from “endangered” to “threatened”, a lesser classification that would not offer as much protection for the imperiled species. Internal communications obtained by the Guardian and Type Investigations show this plan remained a priority for top Trump administration officials at the interior department, but they failed to get the job done before Biden took over.

Last summer, the FWS’s scientific integrity officer concluded that the agency’s official assessment on which it based its downlisting plans did not use the “best available scientific information” and suggested that it should “not be used for decision-making”. As of January 2022, FWS was back at the drawing board, having initiated a new assessment of the Key deer’s status the previous summer, according to a statement the agency sent to the Guardian and Type Investigations. The animal’s future status as an endangered species remains up in the air.

Even if the Key deer does retain some federal protection, however, the FWS’s responsibility to protect animals from rising sea levels remains significantly curtailed – thanks in part to a legal memo issued during the final months of the George W Bush administration.

Observers say the Endangered Species Act could be a powerful tool in the fight against climate change. Under section 7, FWS has the authority to review projects undertaken, funded, or permitted by the federal government if they are likely to harm a protected species. If such projects jeopardize the survival of the species, the agency can force changes or prohibit them altogether. Environmental groups say this gives the FWS leverage to curtail fossil fuel projects or other programs whose emissions contribute to the climate crisis and threaten endangered animals.

In 2008, however, David Bernhardt, the interior department’s top lawyer at the time, signed an internal memo that effectively absolved FWS of responsibility under section 7 to regulate the climate change impacts of greenhouse gas emissions.

The memo stated that: “Where the effects at issue result from climate change potentially induced by [greenhouse gases], a proposed action … is not subject to consultation under the Esa and its implementing regulations.”

Advertisement

The Bernhardt memo now stands as an obstacle to climate action at FWS. It has allowed agencies including the FWS to avoid making tough decisions on greenhouse gas emissions for more than a decade, undermining the government’s ability to control fossil fuel pollution and protect the Key deer, polar bears, shorebirds, sea turtles and other species that face existential danger from melting sea ice, rising temperatures and disappearing habitats. In 2020, for instance, the Trump administration relied in part on the Bernhardt memo to avoid an endangered species consultation on its decision to scrap the Obama-era vehicle emissions standards. (Bernhardt served as interior secretary in the Trump administration.)

Environmental groups hope Biden will change course. In February 2021, a group of top researchers, scientists and academics, including Pimm, wrote Biden asking him to rescind the Bernhardt memo. They urged the agency to more fully consider greenhouse gas pollution as a threat to species protected by the Endangered Species Act. That would mean the climate danger to listed animals like the Key deer could provide a legal basis to apply the Esa in a new way to federally sanctioned fossil fuel projects – this in turn could lead to reform, including to the interior department’s vast oil and gas leasing programs. Fossil fuel production on public lands is the ultimate source of roughly a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States.

“Climate change is the consummate challenge of our time,” said Dr Steven Amstrup, a signatory on the conservationists’ letter to Biden and chief scientist for Polar Bears International. “The US Fish and Wildlife Service should rescind the Bernhardt memo and, as the Esa requires, start addressing the existential threat greenhouse gas pollution poses to plant and animal species across all habitats.”

In response to questions about its continued use of the memo, the FWS said that “the current state of the science is such that we cannot currently establish a causal connection to tie a particular [greenhouse gas]-emitting project to measurable consequences to specific species or critical habitats”.

Amstrup disputes that rationale. He argues that in some cases, in fact, it is possible to measure the climate impact of specific fossil fuel projects on imperiled species – such as the sea level rise that threatens Key deer, or the declining sea ice that strands polar bears – by analyzing accumulated CO2 concentrations.

The interior department, meanwhile, told the Guardian and Type Investigations that it recognizes “an obligation to consider whether our actions contribute to the climate crisis, including the impacts to threatened and endangered species and their habitats.” It did not say whether it plans to rescind the Bernhardt memo.

Advertisement

“I don’t think the Esa by itself is going to solve the climate crisis,” said Brett Hartl, the government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity. But, he added, doing away with the memo “could help support efforts to move [federal agencies] to a much better place”.

Bernhardt, for his part, harshly criticized the letter conservationists sent to Biden.

“Some of the signatories to this letter like former DOI Solicitor John Leshy and former USGS employee Steven Amstrup are longtime activists, who continue to demand unworkable policies, which are not well grounded in the science or the law,” he wrote in a statement. “If successful their efforts will create additional chaos in the Esa interagency consultation process. As a result, I look forward to seeing whether the Biden administration will bend to their will on withdrawing legal opinion when the Obama administration did not.”

Leshy, in response to a request for comment on Bernhardt’s statement, said, “Scientific understanding as well as public consciousness of the close links between climate change and the earth’s rich biodiversity have advanced a great deal since then-Solicitor Bernhardt wrote his opinion in 2008. I expect the Biden administration will take a careful look at the issue his opinion addresses, as it should.”

On Big Pine Key, meanwhile, Nova Silvy continues to observe the Key deer as he has done for more than half a century – watching them rebound from near extinction to become a popular draw for tourists. He even has names for some of them – like Alba, a little doe with white legs. But he thinks the climate crisis is their biggest test yet.

“Unless we can turn it around, I think we are going to be in deep trouble with these deer,” he said. “I mean, I won’t see it – but my daughter may.”

This story was produced in partnership with Type Investigations and supported by the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

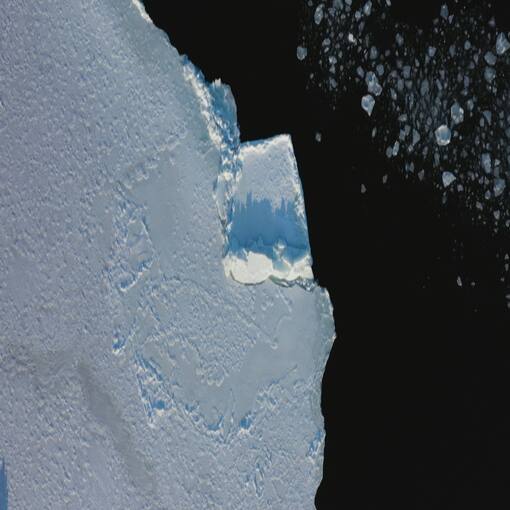

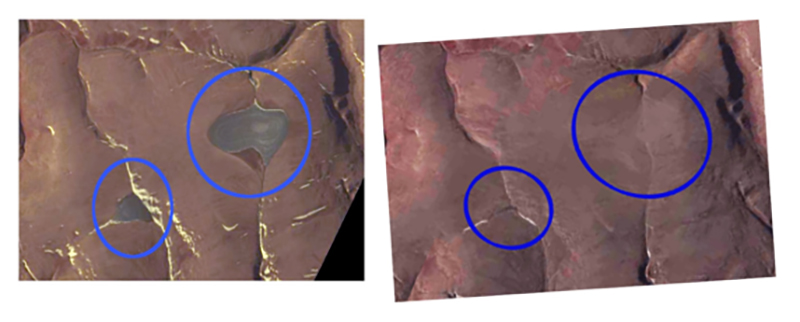

Ice cover in 2015 (left) and 2020 (right). (Bruce Raup/NSIDC)

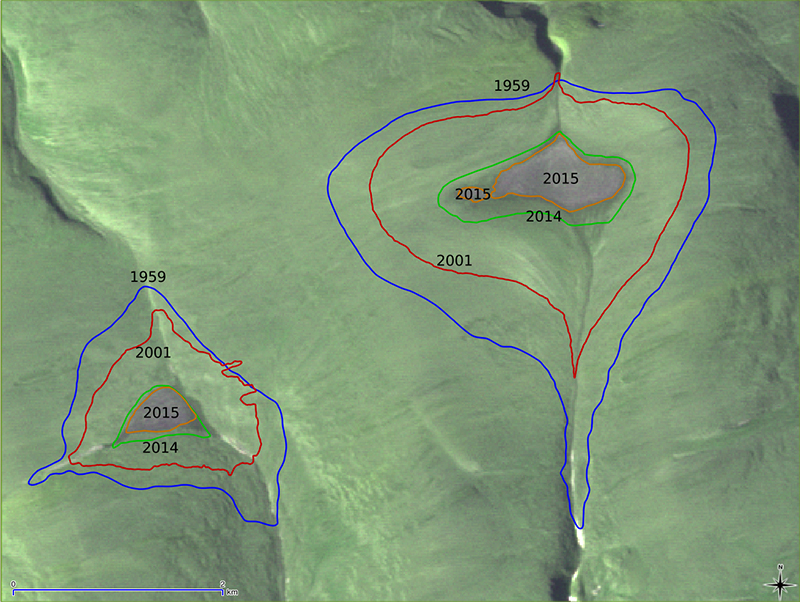

Ice cover in 2015 (left) and 2020 (right). (Bruce Raup/NSIDC) Ice cover tracked over time. (NSIDC)

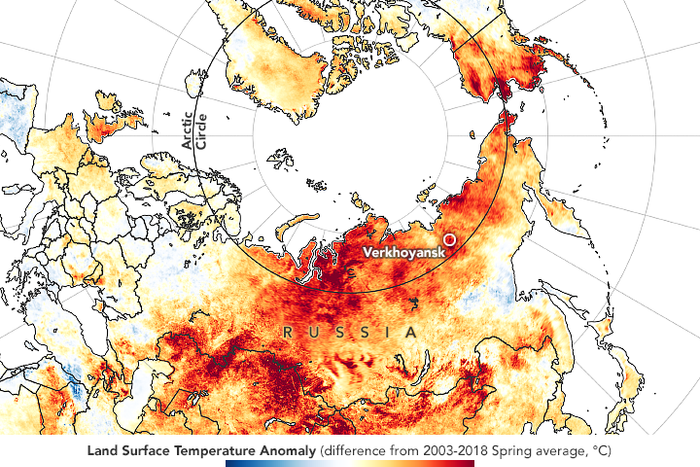

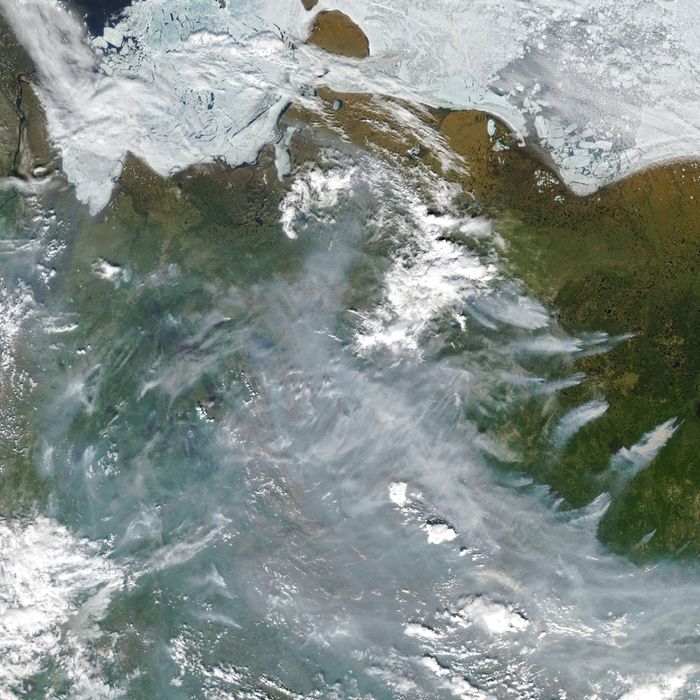

Ice cover tracked over time. (NSIDC) Satellite image of smoke from active fires burning near the Eastern Siberian town of Verkhoyansk, Russia, on June 23, 2020. Photo: Handout/NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite image of smoke from active fires burning near the Eastern Siberian town of Verkhoyansk, Russia, on June 23, 2020. Photo: Handout/NASA Earth Observatory