Polar bears are spending more time on land than they did in the 1990s due to reduced sea ice, new University of Washington-led research shows. Bears in Baffin Bay are getting thinner and adult females are having fewer cubs than when sea ice was more available.

The new study, recently published in Ecological Applications, includes satellite tracking and visual monitoring of polar bears in the 1990s compared with more recent years.

“Climate-induced changes in the Arctic are clearly affecting polar bears,” said lead author Kristin Laidre, a UW associate professor of aquatic and fishery sciences. “They are an icon of climate change, but they’re also an early indicator of climate change because they are so dependent on sea ice.”

The international research team focused on a subpopulation of polar bears around Baffin Bay, the large expanse of ocean between northeastern Canada and Greenland. The team tracked adult female polar bears’ movements and assessed litter sizes and the general health of this subpopulation between the 1990s and the period from 2009 to 2015.

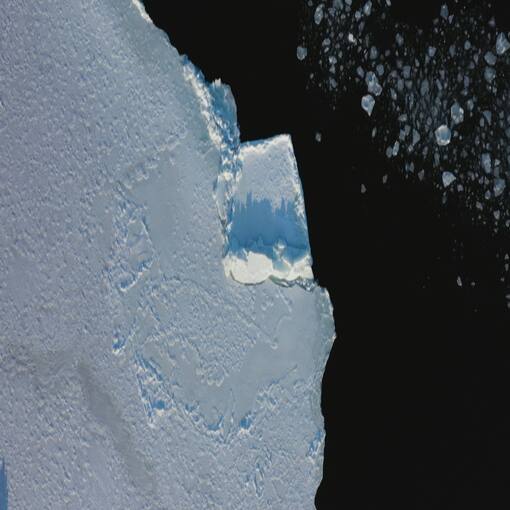

Polar bears’ movements generally follow the annual growth and retreat of sea ice. In early fall, when sea ice is at its minimum, these bears end up on Baffin Island, on the west side of the bay. They wait on land until winter when they can venture out again onto the sea ice.

When Baffin Bay is covered in ice, the bears use the solid surface as a platform for hunting seals, their preferred prey, to travel and even to create snow dens for their young.

“These bears inhabit a seasonal ice zone, meaning the sea ice clears out completely in summer and it’s open water,” Laidre said. “Bears in this area give us a good basis for understanding the implications of sea ice loss.”

Satellite tags that tracked the bears’ movements show that polar bears spent an average of 30 more days on land in recent years compared to in the 1990s. The average in the 1990s was 60 days, generally between late August and mid-October, compared with 90 days spent on land in the 2000s. That’s because Baffin Bay sea ice retreats earlier in the summer and the edge is closer to shore, with more recent summers having more open water.

“When the bears are on land, they don’t hunt seals and instead rely on fat stores,” said Laidre. “They have the ability to fast for extended periods, but over time they get thinner.”

To assess the females’ health, the researchers quantified the condition of bears by assessing their level of fatness after sedating them, or inspecting them visually from the air. Researchers classified fatness on a scale of 1 to 5. The results showed the bears’ body condition was linked with sea ice availability in the current and previous year — following years with more open water, the polar bears were thinner.

The body condition of the mothers and sea ice availability also affected how many cubs were born in a litter. The researchers found larger litter sizes when the mothers were in a good body condition and when spring breakup occurred later in the year — meaning bears had more time on the sea ice in spring to find food.

The authors also used mathematical models to forecast the future of the Baffin Bay polar bears. The models took into account the relationship between sea ice availability and the bears’ body fat and variable litter sizes. The normal litter size may decrease within the next three polar bear generations, they found, mainly due to a projected continuing sea ice decline during that 37-year period.

“We show that two-cub litters — usually the norm for a healthy adult female — are likely to disappear in Baffin Bay in the next few decades if sea ice loss continues,” Laidre said. “This has not been documented before.”

Laidre studies how climate change is affecting polar bears and other marine mammals in the Arctic. She led a 2016 study showing that polar bears across the Arctic have less access to sea ice than they did 40 years ago, meaning less access to their main food source and their preferred den sites. The new study uses direct observations to link the loss of sea ice to the bears’ health and reproductive success.

“This work just adds to the growing body of evidence that loss of sea ice has serious, long-term conservation concerns for this species,” Laidre said. “Only human action on climate change can do anything to turn this around.”

###

Co-authors of the study are Eric Regehr and Harry Stern at the UW; Stephen Atkinson and Markus Dyck at the Government of Nunavut in Canada; Erik Born at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources; Øystein Wiig at the Natural History Museum in Norway; and Nicholas Lunn of Environment and Climate Change Canada. Main funders of the research include NASA and the governments of Nunavut, Canada, Greenland, Denmark and the United States.

For more information, contact Laidre at 206-616-9030 or klaidre@uw.edu.