The United Nations has held countless major meetings on climate change, at great consumption of fuel, that have amounted to nothing but reports and promises of more talk. After many of these alarming reports, the G20 leaders, in November 2014, decided to throw several billions of dollars at the problem. Despite climate-change denial becoming incorrect, as long as a discussion of overpopulation, in the context of climate-change mitigation, remains a taboo, we may be sure that nothing will be achieved. If we are serious about reducing our carbon footprint, we must rethink the flawed capitalist concept of unending economic growth and consider reducing the number of human feet in the world. Overpopulation must be discussed in the context of climate change. A major impediment to this discussion has been the assumption that Africa and Asia would be the main targets for depopulation, with eugenics intent towards “black and brown babies.” In reality, there are too many human babies of all kinds: especially in industrialized countries with high rates of consumption.

A Time Bomb on a Short Fuse

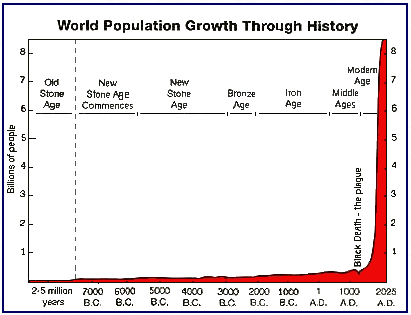

Earth’s current human population is 7.27 billion and it is increasing at a rate of more than one per second: so fast that this will make you dizzy. By the middle of any given day, for example, there are about 205,000 thousand births, compared to 84,000 thousand deaths. Superficially, Asia and Africa are the most populous continents in the world, with the 10 most populated countries being China, India, the United States, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Russia and Japan. On the other hand, if we consider the human impact on greenhouse-gas emissions, the most heavily industrialized countries contribute more per capita to the burden of overpopulation on climate change. Specifically, in 2012, China, the United States, and the European Union alone contributed about 56 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fuels: 29 percent from China, 16 percent from the US, and 11 percent from the EU. India and Russia were a distant fourth and fifth, at respectively, six and five percent. The rest of the entire world only contributed 33 percent of the total carbon emission! This includes all of Africa, South and Central America, Australia, and all the less industrialized countries of Asia.

According to Paul and Ann Ehrlich, who sounded the alarm about overpopulation several decades ago and have analyzed it for many years, “our species’ negative impact on our own life-support systems can be approximated by the equation: I = P x A x T.” In this equation, I, the impact of a population is equal to its size (P), multiplied by the per-capita consumption (A), and finally also multiplied by the energy use (T) for the technologies to drive that consumption. By this analysis, the US is by far the most overpopulated country on the planet. The rapid growth in consumption by China and India, and the global aspiration to follow the US’ footsteps are terrifying and should have dire consequences within 25 years.

The Catastrophic Scenario of Eating Oil

The human population should have crashed from famine in the 1970s but was rescued by modern science. In particular, Norman Borlaug’s green revolution allowed our consumption of food to rely more and more on fossil fuels than on solar energy. We have come to depend on industrial fertilizers that require vast amounts of oil for their production, plus a heavily mechanized agricultural industry that also consumes large quantities of hydrocarbons. Indeed, for many years, the patterns of food, fertilizer, and oil prices over time have been superimposable. Today we can say with confidence, for example, that it takes three quarters of a gallon of oil to produce a pound of beef. Consequently, the idea of cheap oil has become regarded as a guarantee of affordable food. There are three problems with this notion: for one, oil is a finite resource; secondly, in a vicious cycle, cheap and abundant oil will, at best, postpone the inevitable human population crash to a much higher population; and finally, all the oil will eventually wind up in the atmosphere as CO2.

According to a November 2014 report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) that projects the state of the planet and its energy resources to 2040, humans will not have to face a shortage of energy. The IEA projects, that by 2040, the world will consume greenhouse-contributing energy like oil, gas and coal, compared with so-called green energy like wind, solar, and nuclear, in a 1:1 ratio. A world-wide expansion of fracking is expected to keep carbon energy cheap and plentiful. This fact plus a projected two-billion-people increase on Earth mean that energy consumption would increase by 37 percent by 2040. This rate of growth and consumption implies a rapid increase of greenhouse-gas emissions, which in turn translates into a 3.6-degree Celsius global warming by the year 2100. This, according to the IEA report, is a “catastrophic scenario.”

Breeding Ourselves to Extinction

About 20 years ago, when the human population was 5.7 billion, our species was already consuming 40 percent of the Earth’s primary productivity. In other words, 40 percent of the total solar energy converted to organic matter was being consumed by a single species. We are quickly approaching a tipping point in the planet’s sixth mass-extinction event, attributable to human folly. The planet simply cannot accommodate another human doubling. Whether or not there is sufficient hydrocarbon to permit such a doubling, it will be prevented by the ravages of climate-change events, such as floods, hurricanes and droughts due to global warming, by famines due to the disappearance of key members of our ecology like the bats and honeybees, and by infectious diseases, like Ebola, from human infringement on the habitats of other animals. Our runaway overpopulation, overconsumption, and our obsession with economic growth are carving a sure path to collective suicide.

Procreation is still viewed as a being blessing and accomplishment, although this is an obsolete notion from an era when many hands were needed on a farm, and life expectancy was short, especially for women (many of whom died in childbirth) and young children. In an overpopulated world, parenthood is an act of self indulgence: the ultimate act of selfishness against the society at large and even toward the children themselves, who are being delivered to a world in crisis. So far, the only country that has seriously tried to control its population has been China. For the 35 years from 1979 to 2014, China’s unpopular one-child policy helped to avert a population growth of more than 400 million. More recently, China’s capitalist ambitions to grow a domestic market for its goods have led it to relax this policy to allow two children per couple if either parent is an only child.

Population control policy is needed globally and can be achieved without coercion. In most industrialized countries, parenthood currently comes with substantial tax breaks and an assortment of benefits. This must end. Instead, parenthood should be heavily taxed in proportion to the number of children, and adults without children should be those to receive tax breaks. The notion that children are a burden to the community at large — and not a blessing — must become part of the discourse. Ultimately, this should become incorporated in the culture to such a degree that the sight of a mother or father with three or four children will become obscene. To have any future as a species, our population needs to drop, as does our consumption. We must challenge capitalism and adopt a degrowth model. If we are to make any progress on mitigation of climate change, we must urgently address the problem of overpopulation.