•

Snakes – the Chinese krait and the Chinese cobra – may be the original source of the newly discovered coronavirus that has triggered an outbreak of a deadly infectious respiratory illness in China this winter.

The illness was first reported in late December 2019 in Wuhan, a major city in central China, and has been rapidly spreading. Since then, sick travelers from Wuhan have infected people in China and other countries, including the United States.

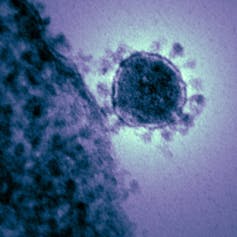

Using samples of the virus isolated from patients, scientists in China have determined the genetic code of the virus and used microscopes to photograph it. The pathogen responsible for this pandemic is a new coronavirus. It’s in the same family of viruses as the well-known severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which have killed hundreds of people in the past 17 years. The World Health Organization (WHO) has named the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV.

We are virologists and journal editors and are closely following this outbreak because there are many questions that need to be answered to curb the spread of this public health threat.

What is a coronavirus?

The name of coronavirus comes from its shape, which resembles a crown or solar corona when imaged using an electron microscope.

Coronavirus is transmitted through the air and primarily infects the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tract of mammals and birds. Though most of the members of the coronavirus family only cause mild flu-like symptoms during infection, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV can infect both upper and lower airways and cause severe respiratory illness and other complications in humans.

This new 2019-nCoV causes similar symptoms to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. People infected with these coronaviruses suffer a severe inflammatory response.

Unfortunately, there is no approved vaccine or antiviral treatment available for coronavirus infection. A better understanding of the life cycle of 2019-nCoV, including the source of the virus, how it is transmitted and how it replicates are needed to both prevent and treat the disease.

Zoonotic transmission

Both SARS and MERS are classified as zoonotic viral diseases, meaning the first patients who were infected acquired these viruses directly from animals. This was possible because while in the animal host, the virus had acquired a series of genetic mutations that allowed it to infect and multiply inside humans.

Now these viruses can be transmitted from person to person. Field studies have revealed that the original source of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV is the bat, and that the masked palm civets (a mammal native to Asia and Africa) and camels, respectively, served as intermediate hosts between bats and humans.

In the case of this 2019 coronavirus outbreak, reports state that most of the first group of patients hospitalized were workers or customers at a local seafood wholesale market which also sold processed meats and live consumable animals including poultry, donkeys, sheep, pigs, camels, foxes, badgers, bamboo rats, hedgehogs and reptiles. However, since no one has ever reported finding a coronavirus infecting aquatic animals, it is plausible that the coronavirus may have originated from other animals sold in that market.

The hypothesis that the 2019-nCoV jumped from an animal at the market is strongly supported by a new publication in the Journal of Medical Virology. The scientists conducted an analysis and compared the genetic sequences of 2019-nCoV and all other known coronaviruses.

The study of the genetic code of 2019-nCoV reveals that the new virus is most closely related to two bat SARS-like coronavirus samples from China, initially suggesting that, like SARS and MERS, the bat might also be the origin of 2019-nCoV. The authors further found that the viral RNA coding sequence of 2019-nCoV spike protein, which forms the “crown” of the virus particle that recognizes the receptor on a host cell, indicates that the bat virus might have mutated before infecting people.

But when the researchers performed a more detailed bioinformatics analysis of the sequence of 2019-nCoV, it suggests that this coronavirus might come from snakes.

From bats to snakes

The researchers used an analysis of the protein codes favored by the new coronavirus and compared it to the protein codes from coronaviruses found in different animal hosts, like birds, snakes, marmots, hedgehogs, manis, bats and humans. Surprisingly, they found that the protein codes in the 2019-nCoV are most similar to those used in snakes.

Snakes often hunt for bats in wild. Reports indicate that snakes were sold in the local seafood market in Wuhan, raising the possibility that the 2019-nCoV might have jumped from the host species – bats – to snakes and then to humans at the beginning of this coronavirus outbreak. However, how the virus could adapt to both the cold-blooded and warm-blooded hosts remains a mystery.

The authors of the report and other researchers must verify the origin of the virus through laboratory experiments. Searching for the 2019-nCoV sequence in snakes would be the first thing to do. However, since the outbreak, the seafood market has been disinfected and shut down, which makes it challenging to trace the new virus’ source animal.

Sampling viral RNA from animals sold at the market and from wild snakes and bats is needed to confirm the origin of the virus. Nonetheless, the reported findings will also provide insights for developing prevention and treatment protocols.

The 2019-nCoV outbreak is another reminder that people should limit the consumption of wild animals to prevent zoonotic infections.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62871800/GettyImages_1075872430.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13700632/Screen_Shot_2019_01_18_at_4.20.49_PM.png)