http://www.hcn.org/articles/the-surprising-history-of-the-malheur-wildlife-refuge?utm_source=wcn1&utm_medium=email

The refuge’s creation helped support nearby ranchers.

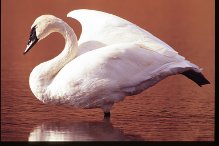

National wildlife refuges such as the one at Malheur near Burns, Oregon, have importance far beyond the current furor over who manages our public lands. Such refuges are becoming increasingly critical habitat for migratory birds because 95 percent of the wetlands along the Pacific Flyway have already been lost to development.

In some years, 25 million birds visit Malheur, and if the refuge were drained and converted to intensive cattle grazing – which is something the “occupiers” threatened to do – entire populations of ducks, sandhill cranes, and shorebirds would suffer. With their long-distance flights and distinctive songs, the migratory birds visiting Malheur’s wetlands now help to tie the continent together.

This was not always the case. By the 1930s, three decades of drainage, reclamation, and drought had decimated high-desert wetlands and the birds that depended upon them. Out of the hundreds of thousands of egrets that once nested on Malheur Lake, only 121 remained. The American population of the birds had dropped by 95 percent. It took the federal government to restore Malheur’s wetlands and recover waterbird populations, bringing back healthy populations of egrets and many other species.

Yet despite the importance of wildlife refuges to America’s birds, not everyone appreciates them. At one recent news conference, Ammon Bundy called the creation of Malheur National Wildlife refuge “an unconstitutional act” that removed ranchers from their lands and plunged the county into an economic depression. This is not a new complaint. Since the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1980s, rural communities in the West have blamed their poverty on the 640 million acres of federal public lands, which make up 52 percent of the land in Western states.

Rural Western communities are indeed suffering, but the cause is not the wildlife refuge system. Conservation of bird habitat did not lead to economic devastation, nor were refuge lands “stolen” from ranchers. If any group has prior claims to Malheur refuge, it is the Paiute Indian Tribe.

For at least 6,000 years, Malheur was the Paiutes’ home. It took a brutal Army campaign to force the people from their reservation, marching them through the snow to the state of Washington in 1879. Homesteaders and cattle barons then moved onto Paiute lands, squeezing as much livestock as possible onto dwindling pastures, and warring with each other over whose land was whose. Scars from this era persist more than a century later.

In 1908, President Roosevelt established the Malheur Lake Bird Reservation on the lands of the former Malheur Indian Reservation. But the refuge included only the lake itself, not the rivers that fed into it. Deprived of water, the lake shrank during droughts, and squatters moved onto the drying lakebed. Conservationists, realizing they needed to protect the Blitzen River that fed the lake, began a campaign to expand the refuge.

But the federal government never forced the ranchers to sell, as the occupiers at Malheur claimed, and the sale did not impoverish the community. In fact, it was just the opposite: During the Depression years of the 1930s, the federal government paid the Swift Corp. $675,000 for ruined grazing lands. Impoverished homesteaders who had squatted on refuge lands eventually received payments substantial enough to set them up as cattle ranchers nearby.

John Scharff, Malheur’s manager from 1935 to 1971, sought to transform local suspicion into acceptance by allowing local ranchers to graze cattle on the refuge. Yet some tension persisted. In the 1970s, when concern about overgrazing reduced – but did not eliminate – refuge grazing, violence erupted again. Some environmentalists denounced ranchers as parasites who destroyed wildlife habitat. A few ranchers responded with death threats against environmentalists and federal employees.

But violence is not the basin’s most important historical legacy. Through the decades, community members have come together to negotiate a better future. In the 1920s, poor homesteaders worked with conservationists to save the refuge from irrigation drainage. In the 1990s, Paiute tribal members, ranchers, environmentalists and federal agencies collaborated on innovative grazing plans to restore bird habitat while also giving ranchers more flexibility. In 2013, such efforts resulted in a landmark collaborative conservation plan for the refuge, and it offers great hope for the local economy and for wildlife.

The poet Gary Snyder wrote, “We must learn to know, love, and join our place even more than we love our own ideas. People who can agree that they share a commitment to the landscape – even if they are otherwise locked in struggle with each other – have at least one deep thing to share.”

Collaborative processes are difficult and time-consuming. Yet they have proven that they have the potential to peacefully sustain both human and wildlife communities.