A Greater Yellowstone grizzly, part of just two healthy populations of grizzly bears in the Lower 48. What effect do mountain bikes have on wilderness and bears? For scientists who study them, there is no doubt. Photo courtesy Steven Fuller

Does mountain biking impact wildlife, any more than hikers and horseback riders do?

More specifically: could rapidly-growing numbers of cyclists in the backcountry of Greater Yellowstone negatively affect the most iconic species—grizzly bears—living in America’s best-known wildland ecosystem?

It’s a point of contention in the debate over how much of the Gallatin Mountains, managed by the U.S. Forest Service, should receive elevated protection under the 1964 Wilderness Act. The wildest core of the Gallatins, located just beyond Yellowstone National Park and extending northward toward Bozeman’s back door, is the 155,000-acre Buffalo-Porcupine Creek Wilderness Study Area.

Not only is the fate of the Gallatins considered a national conservation issue, considering its importance to the health of the ecosystem holding Yellowstone, but lines of disagreement have opened within the conservation community.

The Gallatin Forest Partnership, led by the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, The Wilderness Society, Montana Wilderness Association and aligned with mountain biking groups, is seeking to have 102,000 acres protected as wilderness in the Gallatins, but it doesn’t include the Buffalo Horn-Porcupine.

“So far I have only seen people who want mountain bikers to sacrifice and the assumption [is] that this will help wildlife,” wrote Adam Oliver, founder of the Southwest Montana Mountain Bike Association recently on the Bozone Listserv. “Show me the science, prove me wrong.”

Meanwhile, another group, Montanans for Gallatin Wilderness and its allies, want 230,000 acres elevated to wilderness status, especially the Buffalo Horn-Porcupine. Their proposal has attracted widespread support from prominent conservation biologists, retired land managers and well-known businesspeople and citizens across the country. They say they aren’t anti-mountain biking; rather, they are “pro-grizzly bear” and favor foresighted wildlife protection in an age of climate change, a rapidly-expanding human development footprint emanating from Bozeman and Big Sky, and rising levels of outdoor recreation.

One flashpoint playing out publicly has been an online forum called the Bozone Listerv, which functions essentially as a digital community bulletin board. There, cycling advocates have claimed that riding their bikes in grizzly country does not cause serious impacts—certainly none worse, they insist, than hikers, horseback riders and motorized recreationists.

If the Buffalo Horn-Porcupine has its status elevated from being a wilderness study area to full Capital “W” wilderness, motorized users as well as mountain bikers would be prohibited. However, illegal incursion and blazing of trails by motorized users and mountain bikers have already occurred in the wilderness study area with little enforcement coming from the Forest Service.

“So far I have only seen people who want mountain bikers to sacrifice and the assumption [is] that this will help wildlife,” wrote Adam Oliver, founder of the Southwest Montana Mountain Bike Association recently on the Bozone Listserv. “Show me the science, prove me wrong or be willing to give up something yourself.”

If Mr. Oliver desires to be shown the professional science relating to mountain bikes and concerns about grizzlies, he need only contact Dr. Christopher Servheen. Servheen, retired from government service, spent four decades at the helm of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Grizzly Bear Recovery Team in the West. He is an adjunct research professor in the Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences at the University of Montana.

Servheen says that despite assertions by mountain bikers, the scientific evidence on impact is pretty clear based on human-bear incidents that have happened and thousands of hours of field observation and radio tracking of grizzlies.

“I do believe that mountain bikes are a grave threat to bears—both grizzly and black bears—for many reasons and these are detailed in the Treat report and recommendations,” Servheen told Mountain Journal. “High speed and quiet human activity in bear habitat is a grave threat to bear and human safety and certainly can displace bears from trails and along trails. Bikes also degrade the wilderness character of wild areas by mechanized travel at abnormal speeds.”

“I do believe that mountain bikes are a grave threat to bears—both grizzly and black bears—for many reasons…” Christopher Servheen told Mountain Journal. “High speed and quiet human activity in bear habitat is a grave threat to bear and human safety and certainly can displace bears from trails and along trails. Bikes also degrade the wilderness character of wild areas by mechanized travel at abnormal speeds.”

By “Treat report,” Servheen is referring to a

multi-agency Board of Review investigation into the death of Brad Treat who was fatally mauled by a grizzly on June 29, 2016 after colliding with the bear at high speed near the town of East Glacier, just outside of Glacier National Park in Montana. Servheen chairs that board and others investigating fatal bear maulings.

Investigators surmised that Treat was traveling at between 20 and 25 miles an hour and rode into the grizzly around a sharp turn in the trail, leaving him only a second or two to respond. The bear then responded defensively, demonstrating no pattern of otherwise being aggressive and no interest in consuming Treat. He was not carrying bear spray, a gun or a cell phone.

° ° °

Mountain bikers often write on social media of how they enjoy getting hardy workouts over long distances which means they need to ride fast. Some also boast of their love for careening down steep trails.

Denial about impacts on wildlife is a common defensive response from mountain biking groups now pushing for construction of more riding trails on public lands, seeking to reduce the size of areas being proposed for federal wilderness status, and even enlisting lawmakers to amend the federal Wilderness Act so they can gain more access to wild country.

Servheen and others have seen claims made by mountain bikers who try to suggest there is no scientific evidence they’re affecting wildlife. “Some selfish and self-centered mountain bikers are especially prone to this,” Servheen said. “The key factors of mountain biking that aggravate its impact on wildlife are high speed combined with quiet travel. These factors are exactly what we preach against when we tell people how to be safe when using bear habitat.”

For years, mountain biking advocates—as they did at a SHIFT outdoor recreation conference in Jackson Hole—have suggested it makes no difference whether one is riding in Moab and the Wasatch, the Sierras, Colorado Rockies or northern Rockies. Impacts to wildlife, they insist, are nominal.

None of those other areas possess the same level of large mammal diversity Greater Yellowstone does and, save for the Crown of the Continent/Continental Divide Ecosystem in northern Montana, they don’t have grizzlies, considered an umbrella species for a long list of other animals.

Federal wilderness girds the southwest, southwest and eastern front of Yellowstone National Park, serving as a continuance of habitat for species that rely upon plenty of space and low densities of people. The Gallatins, pictured above, represent a crucial piece roadless land, north of the national park. Advocates have sought to get the Gallatin crest and its foothills protected for a century in recognition of the high wildlife values.

According to Servheen and others, capital “W” wilderness areas are biologically important for bears because they are notably different from the busy pace of human uses found on public lands managed for multiple use. Wilderness does accommodate recreation but the emphasis is on users moving at slow speed.

It’s no accident that grizzlies select for unfragmented roadless habitat and wilderness in the Gallatins is certain to accrue ever more value for wildlife as human use levels in the Yellowstone River valley, to the east, and the Gallatin River corridor, dominated by exploding development at Big Sky, continue to surge.

“Wild public lands that currently have grizzly bears present have those bears because of the characteristics of these places: visual cover, secure habitat, natural foods, and spring, summer, fall and denning habitat,” Servheen said. “All these factors can be compromised by excessive human presence, high speed and high encounter frequencies with humans. To compare places without bears, like Utah, to places with bears, like Yellowstone or all the wilderness areas with bears, is a flawed comparison.”

Sharing the Board of Review’s findings and other scientific analyses, Servheen said, “I see mountain bikes as a threat to human and bear safety in grizzly and black bear habitat and as an unnecessary disturbance in wilderness and roadless areas.”

As part of its forest planning process which will guide management for a human generation, Custer-Gallatin officials will be compiling public comments about differing options being advanced for protecting the Gallatin Range and other parts of the forest as wilderness.

Observers note that should Gallatin managers choose to “release” wilderness study areas for motorized recreation or mountain biking (and the growing controversy over e-bikes) those lands will be disqualified from Wilderness designation in the future.

That’s why, given growing population pressure, proponents of more wilderness say the Custer-Gallatin needs to think proactively, anticipating the fact that habitat for grizzlies will shrink and become ever-more fragmented by rising intensity of recreational use. Further, once a use is established, it is extremely difficult to reel it back in. By the time wildlife field personnel realize that grizzlies are being displaced, it can often be too late.

° ° °

Bear biologists say that because hiking and horseback riding happens at slower plodding speeds, such behavior is more predictable for grizzlies. Both mountain bikers and motorized users increase the likelihood of surprising bears and the fact that riders are focused on the trail, to avoid hitting a boulder or colliding with a tree, they are not as attentive. It’s the growing numbers of mountain bikers overall, and the volume of riders on any given day, that concerns Servheen.

To show how fast mountain biking has emerged as user entity, reference the voluminous document titled “Forest Plan Amendment for Grizzly Bear Conservation in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” released in 2006. The plan pertains to all of the national forests in the Greater Yellowstone region and highlights changes necessary to solidify grizzly conservation in advance of them being removed from federal protection under the Endangered Species Act.

The document contains hundreds of thousands of words but “bike” is mentioned just twice. Today, mountain biking may be the fastest growing outdoor recreation pastime in Greater Yellowstone and forest supervisors, as a whole, admit they don’t know what the impacts are on wildlife now and, most importantly, what they will be in the future.

Ten years after the document mentioned, above, was released, the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee released its “Conservation Strategy for the Grizzly Bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.” In that document, the importance of “secure habitat” in the core of the ecosystem, which includes roadless stretches of the Gallatin Range, was spelled out:

“History has demonstrated that grizzly bear populations survived where frequencies of contact with humans were very low. Populations of grizzly bears persisted in those areas where large expanses of relatively secure habitat were retained and where human-caused mortality was low,” it states. “In the GYE, this is primarily associated with national park lands, wilderness areas, and large blocks of public lands. Habitat security requires minimizing mortality risk and displacement from human activities in a sufficient amount of habitat to allow the population to benefit from this secure habitat and respond with increasing numbers and distribution.”

Conservation proponents of more wilderness in the Gallatins say they are pro-grizzly, not anti-mountain biking, asserting that the area is more important for long-term survival of grizzlies in Greater Yellowstone than mountain bikers’ need for more terrain. Grizzly photo courtesy Thomas D. Mangelsen (mangelsen.com). Mountain biker photo courtesy Leslie Kehmeier (www.flickr.com/photos/mypubliclands/20753967159). Composite image produced by Gus O’Keefe/Mountain Journal

Mountain bikers already have hundreds of miles’ worth of trail riding options within a relatively short driving distance from Bozeman and Big Sky on public and private lands, including over 50 miles of trail at Big Sky Resort and the Yellowstone Club. Ecoystemwide, they have thousands of miles if old logging roads and motorized trails are included.

Wildlife, however, does not have such a range of options. Grizzly bears fare better in solitude and they settle where necessity bring them. Besides bruins, some elk calving areas are many generations old—places where mothers, who were taught by their mothers, and so on, go to calf and raise their young where they are less likely to encounter human disturbance.

“There are two main impacts of roads and trails on bears: displacement and increased mortality risk,” Servheen explains. “These impacts occur with both motorized and non-motorized access. As human use increases, the importance of areas where there is little or rare use by humans increases. If recreation increases to the point that bears have few secure places to be, then there can be many complex impacts.”

Servheen cited the example of adult male bears seeking and using the most secure backcountry areas thereby forcing females with offspring into areas closer to humans and human disturbance as they try to avoid the adult males.

That’s, in fact, precisely what happened with famed Jackson Hole Grizzly 399 whose first cub was likely killed by a large male bear a decade and a half ago. She then moved from the backcountry of the Bridger-Teton and Grand Teton National Park to riskier roadside area to raise broods of cubs.

“Fortunately, we have yet to get to the point of extreme displacement in most areas of grizzly habitat, but it certainly is possible if human use continues to increase in important bear habitat,” Servheen explains.

The point is not having human uses of backcountry areas proliferate to the point where that happens. In the past, it was documented that old logging roads were linked to higher levels of elicit killing of grizzlies because they provided easy access. That’s not Servheen’s worry with recreation trails.

“As for poaching, I define poaching as intentional vandal killing of bears. I doubt that increased human use will result in more poaching but it could result in more self-defense kills of bears as bears are surprised and perhaps defensive in more remote areas, he said. “I worry less about direct deaths than I do about continual displacement and stress on bears trying to avoid humans wherever they go.”

° ° °

A dozen years ago, in 2007, Jeff Marion and Jeremy Wimpey published an assessment, “Environmental Impacts of Mountain Biking: Science Review and Best Practices.” Most of review focused on such things as soil erosion and minimizing conflicts with other users. Notably, it was published as a companion to IMBA’s widely-circulated how-to book on trail building titled “Trail Solutions.”

While no mention was made of grizzly bears—in fact, just two viable grizzly populations exist in the Lower 48—Servheen speaks favorably of Marion’s and Wimpey’s recitation of the science.

“Trails and trail uses can also affect wildlife. Trails may degrade or fragment wildlife habitat, and can also alter the activities of nearby animals, causing avoidance behavior in some and food-related attraction behavior in others. While most forms of trail impact are limited to a narrow trail corridor, disturbance of wildlife can extend considerably further into natural landscapes.”

They went on, “The opposite conduct in wildlife— avoidance behavior —can be equally problematic. Avoidance behavior is generally an innate response that is magnified by visitor behaviors perceived as threatening, such as loud sounds, off-trail travel, travel in the direction of wildlife, and sudden movements. When animals flee from disturbance by trail users, they often expend precious energy, which is particularly dangerous for them in winter months when food is scarce. When animals move away from a disturbance, they leave preferred or prime habitat and move, either permanently or temporarily, to secondary habitat that may not meet their needs for food, water, or cover. Visitors and land managers, however, are often unaware of such impacts, because animals often flee before humans are aware of the presence of wildlife.”

Thus, here is a contraction: mountain bikers are told to make noise in order to alert bears of their presence and yet making noise, particularly if it involves people over a long period of time, might displace grizzlies from habitat.

° ° °

The Board of Review report examining Treat’s death states, “There is a long record of human-bear conflicts associated with mountain biking in bear habitat including the serious injuries and deaths suffered by bike riders. Both grizzly bears and black bears have been involved in these conflicts with mountain bikers,” the authors wrote then drew the following comparison between prime grizzly areas around Yellowstone and the Canadian Rockies near Banff National Park.

“Safety issues related to grizzly bear attacks on trail users in Banff National Park prompted Herrero to study the Moraine Lake Highline Trail. Park staff noted that hikers were far more numerous than mountain bikers on the trail, but that the number of encounters between bikers and bears was disproportionately high….Previous research had shown that grizzly bears are more likely to attack when they first become aware of a human presence at distances of less than 50 meters. Herrero…concluded that mountain bikers travel faster, more quietly and with closer attention to the tread than hikers, all attributes that limit place on a fast section of trail that went through high-quality bear habitat.”

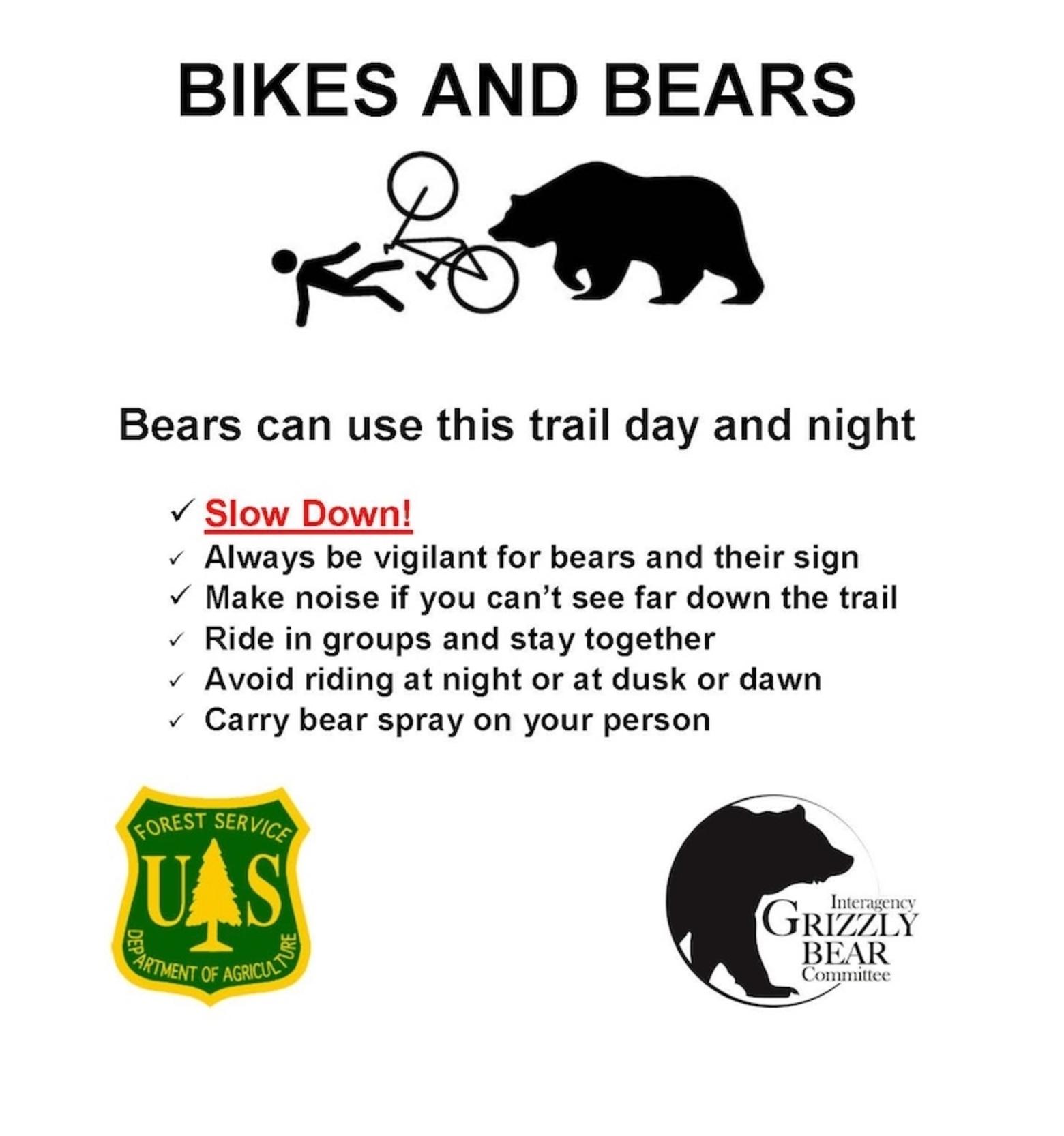

“Herrero” is Dr. Stephen Herrero, an animal behaviorist considered a world authority on bear attacks. He wrote the widely-cited book Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance. The Board of Review ended its report with this: “There is a need for enhanced safety messaging at trailheads and in the media but it is usually aimed at hikers. However, mountain biking is in many ways more likely to result in injury and or death from bear attacks to people who participate in the activity. In addition, there are increasing numbers of mountain bikers using bear habitat and pressure to increase mountain bike access to areas where black bear and grizzly bear encounters are very likely.”

There is also this analysis done in Jackson Hole. In 2014, consultant A. Grant MacHutchon was hired to compile a risk assessment on human-bear interaction in the Moose-Wilson road corridor. It connects Teton Village and dense development along the west side of the Snake River in Jackson Hole with Grand Teton National Park.

Again, it’s not only displacement of grizzlies, as Servheen and others note, but a matter of human safety.

“Trail riding with mountain bikes is currently not allowed anywhere in the Moose-Wilson Corridor nor is it being proposed in any of the alternatives for the MWC. However, there is more information available on the human safety risks associated with mountain biking than there is for road biking on multi‐use pathways; consequently, I used this information for my assessment of the proposed multi‐use pathway.”

Based on his congealing of studies, he said a sudden encounter occurs when a person approaches within 55 yards of a bear, apparently without the bear being aware of the person until the person is close by.

“Mountain biking is often characterized by high speeds and quiet movement. This limits the reaction time of people and/or bears and the warning noise that would help to reduce the chance of sudden encounters with a bear. An alert mountain biker making sufficient noise and traveling at slow speed (e.g. uphill) would be no more likely to have a sudden encounter with a bear than would a hiker. However, on certain types of trails (e.g. flat, moderate downhill, smooth surface), the typical bicyclist can travel at much higher speeds than hikers, which increases the likelihood of a sudden encounter.”

“An alert mountain biker making sufficient noise and traveling at slow speed (e.g. uphill) would be no more likely to have a sudden encounter with a bear than would a hiker. However, on certain types of trails (e.g. flat, moderate downhill, smooth surface), the typical bicyclist can travel at much higher speeds than hikers, which increases the likelihood of a sudden encounter.” —Wildlife research consultant A. Grant MacHutchon

Matthew Schmor, a graduate student at the University of Calgary, summarized survey data he collected from 41 individuals in the Calgary‐Canmore region who had had interactions with bears while mountain biking. Some of the interactions were aggressive encounters in which a bicyclist(s) was charged or chased by a bear(s). Most of the interactions (66 percent) were with black bears (27 of 41), 32 percent were with grizzly bears (13 of 41), and in one case the species was not identified.

Of the 41 bear‐bicyclist interactions reported by Schmor, most occurred on flat trails (51 percent vs nearly a third—29 percent—on downhills, and 15 percent on uphill riding. Equally as revealing is that 61 percent happened at speeds of 11 and 30 km/hour, a quarter at between 1 and 10 km/hour. Three-fifths of the incidents involved two or less riders.

“Interestingly, Schmor found that 78 percent (32 of 41) of encounters occurred in high visibility areas with greater than 16 yards of open ground between the bicyclist and the bear. Schmor also found that 76 percent (31 of 41) of mountain bike riders had not contacted officials about their bear encounters.”

The latter finding is extremely important because each encounter can result cumulatively over time in bears being disrupted and opting to abandon prime habitat for terrain where food and security cover is much less optimal. For grizzly mothers in their reproduction years, biologists tell Mountain Journalthat poorer nutrition and more stressful environments can actually result in fewer successful pregnancies and fewer cubs.

If grizzly bears in an ecosystem like Greater Yellowstone are going to persist and thrive, weathering changes brought by growing numbers of people and a shifting climate, they protecting the best bear habitat should be a priority, Servheen says. “You are correct that I see mountain bikes as a threat to human and bear safety in grizzly and black bear habitat and as an unnecessary disturbance in wilderness and roadless areas,” he said.

What’s the key to keeping free-ranging wildlife populations on the landscape? What’s the value of wilderness? What should conservation-minded recreationists be paying attention to? “Intactness is the first thing that comes to mind. There are few places left intact in our highly fragmented world,” says Gary Tabor, president of the Center for Large Landscape Conservation based in Bozeman but involved with wildlife issues around the world.

“I think mountain biking and rapid recreational expansion into the backcountry is symptomatic of a growing push to build roads and sub-roads and trails everywhere we want to go without regard for the other beings out there and the high values inherent in leaving those places alone.”

Tabor says the thinking about wildness has changed in an era focused on personal use and extreme athleticism. Lost is a literacy and understanding of ecology, an empathy for what uncommon creatures need in the rare spaces they’re able to inhabit.

Tabor has watched the debate over Gallatin wilderness unfold on social media outlets and he has witnessed professional conservationists affiliated with the Gallatin Forest Partnership become defensive when other groups say that more habitat protection is better than promoting more human use. It isn’t hard to know which conservation option is better for wildlife.

“Groups that are working on behalf of the conservation community to represent conservation values should be open to peer review from other members of the conservation community,” he said. “They should not look upon it as criticism but welcome it as peer review to put forth a better conservation plan because we probably have one chance to get it right. Just because you are one of the few in a negotiating room doesn’t mean you capture all of the conservation values that need a louder voice. As the fragmentation of nature accelerates and the future of the Gallatins is being decided, I think we all can ask ourselves, “Is no place sacred?”