The global environment is collapsing and dying under the weight of inequitable over-population and ecosystem loss.

“We learn the meaning of enough and how to share or it is the end of being.” ― Dr. Glen Barry

The surging Ebola epidemic is the result of broad-based ecological and social collapse including rainforest loss, over-population, poverty and war. This preventable environmental and human tragedy demonstrates the extent to which the world has gone dramatically wrong as ecosystem collapse, inequity, grotesque injustice, religious extremism, nationalistic militarism, and resurgent authoritarianism threaten our species and planet’s very being.

Any humane person is appalled by the escalating Ebola crisis, and let’s be clear expressing these concerns regarding causation is NOT an attempt to hijack a tragedy. Things happen for a reason, and Ebola was preventable, and future catastrophes of potentially greater magnitude can be foreseen and avoided by the truth.

The single greatest truth underlying the Ebola tragedy is that humanity is systematically dismantling the ecosystems that make Earth habitable. In particular, the potential for Ebola outbreaks and threats from other emergent diseases is made worse by cutting down forests [1]. Exponentially growing human populations and consumption – be it subsistence agriculture or mining for luxury consumer items – are pushing deeper into African old-growth forests where Ebola circulated before spillover into humans.

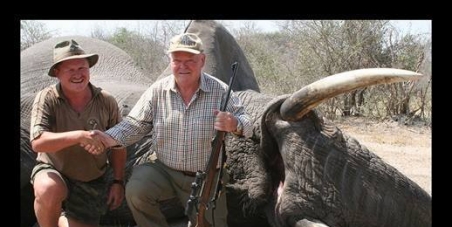

Poverty stricken communities in West Africa are increasingly desperate, and are eating infected “bushmeat” such as bats and gorilla, bringing them into contact with infected wildlife blood. Increasingly fragmented forests, further diminished by climate change, are forcing bats to find other places to live that are often amongst human communities.

Some 90% of West Africa’s original forests have already been lost. Over half of Liberia’s old-growth forests have recently been sold for industrial logging by President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s post-war government. Only 4% of Sierra Leone’s forest cover remains and they are expected to totally disappear soon under the pressure of logging, agriculture, and mining.

My recently published peer-reviewed scientific research [2] on ecosystem loss and biosphere collapse indicates more natural ecosystems have been lost than the global environment can handle without collapsing. Recently published science reports that 50% of Earth’s wildlife has died (in fact been murdered) in the last 40 years [3].

Loss of natural life-giving habitats has consequences. We are each witnesses to and participants in global ecosystem collapse.

There are other major social ills which potentially foster global pandemics. Rising inequity, abject poverty, and lack of justice threaten Earth’s and humanity’s very being. These ills and global ecosystem collapse are causing increased nationalistic war, migration and rise of authoritarian corporatism. West Africa has been ravaged by war and poverty for decades, which shows little signs of abating, particularly since natural habitats for community based sustainable development are nearly gone.

War breeds disease. It is no coincidence that the 1918 flu pandemic – the last great global disease outbreak that killed an estimated 50-100 million – occurred just as the ravages of World War I were ending. Conditions after ecosystems are stripped by over-population and poverty are not that different – each providing ravaged landscapes that are prime habitat for disease organisms.

West Africa’s ecological collapse has brought people into contact with blood from infected animals causing the Ebola epidemic. Once human infection occurs, ecologically denuded, conflict ridden, over-populated, and squalid impoverished communities are ripe for a pandemic. As the Ebola virus threatens to become endemic to the region, it potentially offers a permanent base from which infections can indefinitely continue to spread globally.

Since 911 America has slashed all other spending as it militarizes, viewing all sources of conflict as resolvable by waging perma-war. Africa needs doctors and the U.S. sends the military. Both terrorism and infectious disease are best prevented by long-term investments in equitably reducing poverty and meeting human needs – including universal health-care, living wage jobs, education, family planning, and establishment of greater global medical rapid response capabilities.

We are all in this together. Our over-populated, over-consuming, inequitable human dominated Earth continues to wildly careen toward biosphere collapse as sheer sum consumption overwhelms nature. West Africa’s 2010 population of 317 million people is still growing at 2.35%, and is expected to nearly double in 25 years, even as squalor, lack of basic needs, ecosystem loss, and pestilence increase. This can never, ever be ecologically or socially sustainable, and can only end in ruin.

Equity, education, condoms, and lower taxes and other incentives to stabilize and then reduce human population are a huge part of the solution for a just, equitable, and sustainable future. Otherwise Earth will limit human numbers with Ebola and worse. It may be happening already.

We are one human family and in a globalized world no nation is an island unto itself. By failing to invest in reducing poverty and in meeting basic human needs in Africa and globally (even as we temporarily enrich ourselves by gorging upon the destruction of their natural ecosystems), we in the over-developed world ensure that much of the world is fertile ground for disease and war. There is no way to keep Ebola and other social and ecological scourges out of Europe and America if they overwhelm the rest of humanity.

Ebola is what happens when the rich ignore poverty, as well as environmental and social decline, falsely believing they are not their concern. There can be no security ever again for anybody as long as billions live in abject poverty on a couple dollars a day as a few hundred people control half of Earth’s wealth.

We learn the meaning of enough and how to share or it is the end of being.

Walmart parking lots and iPads don’t sustain or feed you. Healthy ecosystems and land do. The hairless ape with opposable thumbs – that once showed so much potential – has instead become an out of control, barbaric and ecocidal beast with barely more sentience of its environmental constraints than yeast on sugar.

Ebola is very, very serious but can be beat with public health investments, coming together and showing courage, and by dealing with underlying causes. In the short-term, it is absolutely vital that the world organizes a massive infusion of doctors and quarantined hospital beds into West Africa immediately, even as we work on the long-term solutions highlighted here.

Ultimately commitments to sustainable community development, universal health care and education, free family planning, global demilitarization, equity, and ecosystem protection and restoration are the only means to minimize the risk of emergent disease. Unless we come together now as one human family and change fast – by cutting emissions, protecting ecosystems, having fewer kids, ending war, investing in ending abject poverty, and embracing agro-ecology – we face biosphere collapse and the end of being.

A pathway exists to global ecological sustainability; yet it requires shared sacrifice and for us all to be strong, as we come together to vigorously resist all sources of ecocide. It is up to each and every one of us to commit our full being to sustaining ecology and living gently upon Earth… or our ONE SHARED BIOSPHERE collapses and being ends

I desperately hope that Ebola does not become a global pandemic killing hundreds of millions or even billions. But if it does, it is a natural response from an Earth under siege defending herself from our own ignorant yet willful actions. We have some urgent changes to make as a species, let’s get going today before it is too late.

###

[1] We Are Making Ebola Outbreaks Worse by Cutting Down Forests: Mother Jones

[2] Barry, G. (2014), “Terrestrial ecosystem loss and biosphere collapse”, Management of Environmental Quality, Vol. 25 No. 5, pp. 542-563. Read online for personal use only: http://bit.ly/MEQ_Biosphere

[3] Living Planet Index: Zoological Society of London and WWF

Support Earth through a donation to EcoInternet at http://www.climateark.org/shared/donate/

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62871800/GettyImages_1075872430.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13700632/Screen_Shot_2019_01_18_at_4.20.49_PM.png)

Cooked or smoked bushmeat is not usually harmful

Cooked or smoked bushmeat is not usually harmful Many West Africans eat bushmeat

Many West Africans eat bushmeat It is sold in markets across the region

It is sold in markets across the region More than 100,000 bats are thought to be eaten in Ghana each year

More than 100,000 bats are thought to be eaten in Ghana each year