By Laura Paddison, CNN

6 minute read

Published 1:00 AM EDT, Sat October 12, 2024

Elephants feed in Hwange National Park in northern Zimbabwe on December 16, 2023. Zinyange Auntony/AFP/Getty ImagesCNN —

Drought is now so bad in parts of southern Africa that governments say they must kill hundreds of their most captivating, majestic wild animals to feed desperately hungry people.

In August, Namibia announced it had embarked on a cull of 723 animals, including 83 elephants, 30 hippos and 300 zebras. The following month, Zimbabwe authorized the slaughter of 200 elephants.

Both governments said the culls would help alleviate the impacts of the region’s worst drought in 100 years, reduce pressure on land and water, and prevent conflict as animals push further into human settlements seeking food.

But it’s triggered a fierce argument.

Conservationists have criticized the cullings as cruel and short-termist, setting a dangerous precedent.

The decision to offer up some of Namibia’s elephants to trophy hunters — tourists, often from the US and Europe, who pay thousands of dollars to shoot animals and keep body parts as trophies — has further fueled opposition and raised questions about governments’ motivations.

For some supporters of the cull, however, critics misunderstand conservation at best, and are “racist” at worst — telling African countries what to do and valuing wildlife over people.

An elephant grazes inside the Murchison Falls National Park in northwest Uganda on February 20, 2023. Badru Katumba/AFP/Getty Images

Elephants in the Huanib River Valley in northern Damaraland and Kaokoland, Namibia. Getty Images

It’s a heated debate that goes to the heart of what conservation looks like and how countries will deal with deep, devastating droughts that are only becoming more frequent as humans burn fossil fuels and heat up the world.

‘Immense suffering’

The situation facing southern Africa is dire. Crops have failed, livestock has died and nearly 70 million people are desperately in need of food.

Zimbabwe declared a national disaster in April. Namibia followed in May, declaring a state of emergency as drought left around half its population facing high levels of acute food insecurity.

The drought has been driven by El Niño — a natural climate pattern which has led to sharply reduced rainfall in the region — and exacerbated by the human-caused climate crisis.

“The reality is we are seeing an unprecedented increase in droughts,” said Elizabeth Mrema, deputy executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme. “There is immense suffering.”

Legal harvesting and consumption of wild game for food is common practice in cultures across the world, Mrema told CNN. “Provided the harvesting of these animals is done using scientifically proven, sustainable methods … there should be no cause for concern.”

Both countries say the culls won’t threaten the long-term survival of wild animal populations. They say it’s the opposite: reducing numbers will help protect remaining animals as the drought shrinks food and water resources.

All the animals in Zimbabwe and most in Namibia will be killed by professional hunters.

The animals will be shot, said Chris Brown, an environmental scientist at the Namibian Chamber of Environment, an association of conservation groups, which supports the cull. “Mostly it’s done at night with a silencer and an infrared spot so you can get very close to the animals. Headshot, animals drop,” Brown told CNN.

It’s “very humane,” he said, in contrast to farm animals squeezed into trucks before being killed in slaughterhouses. The meat will then be distributed to those in need.

Around 12 of the 83 Namibian elephants earmarked for the cull, however, will be killed by trophy hunters, Romeo Muyunda, spokesperson for Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, told CNN.

This has led to an outcry. A report by 14 African conservationists, who say they must remain anonymous due to the risks of speaking out, says courting trophy hunters raises questions about “the real motive.”

Muyunda said none of the money would go to the government, instead the aim is to generate money for communities affected by human-wildlife conflict.

‘Cruel and misguided’

Elephants may be a prized sight on safari, but they can be dangerous for those living alongside them.

In Namibia, which has around 21,000 elephants, according to a 2022 survey, some areas have so many they have become “almost intolerable for people,” Brown said, with elephants destroying crops, harming livestock and even killing people.

The country has attempted to offload elephants before. In 2020, it announced an auction of 170, but only managed to sell a third of them. They cannot be sold or given away, Brown said, “the truth of the matter is that no one wants elephants.”

But others don’t buy the overpopulation argument.

“Namibia’s wildlife have survived but diminished over the last 12 years of droughts,” said Izak Smit, chairperson of Desert Lions Human Relations Aid, a Namibian non-profit. This is especially true in areas of the country where the culls will take place, he told CNN.

Bottles with homemade, non-lethal repellents around a perimeter fence at a homestead in Dete near Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe on May 25, 2022. Zinyange Auntony/AFP/Getty Images

In Zimbabwe, where the government says there are more than 85,000 elephants, some experts are concerns numbers have been overinflated.

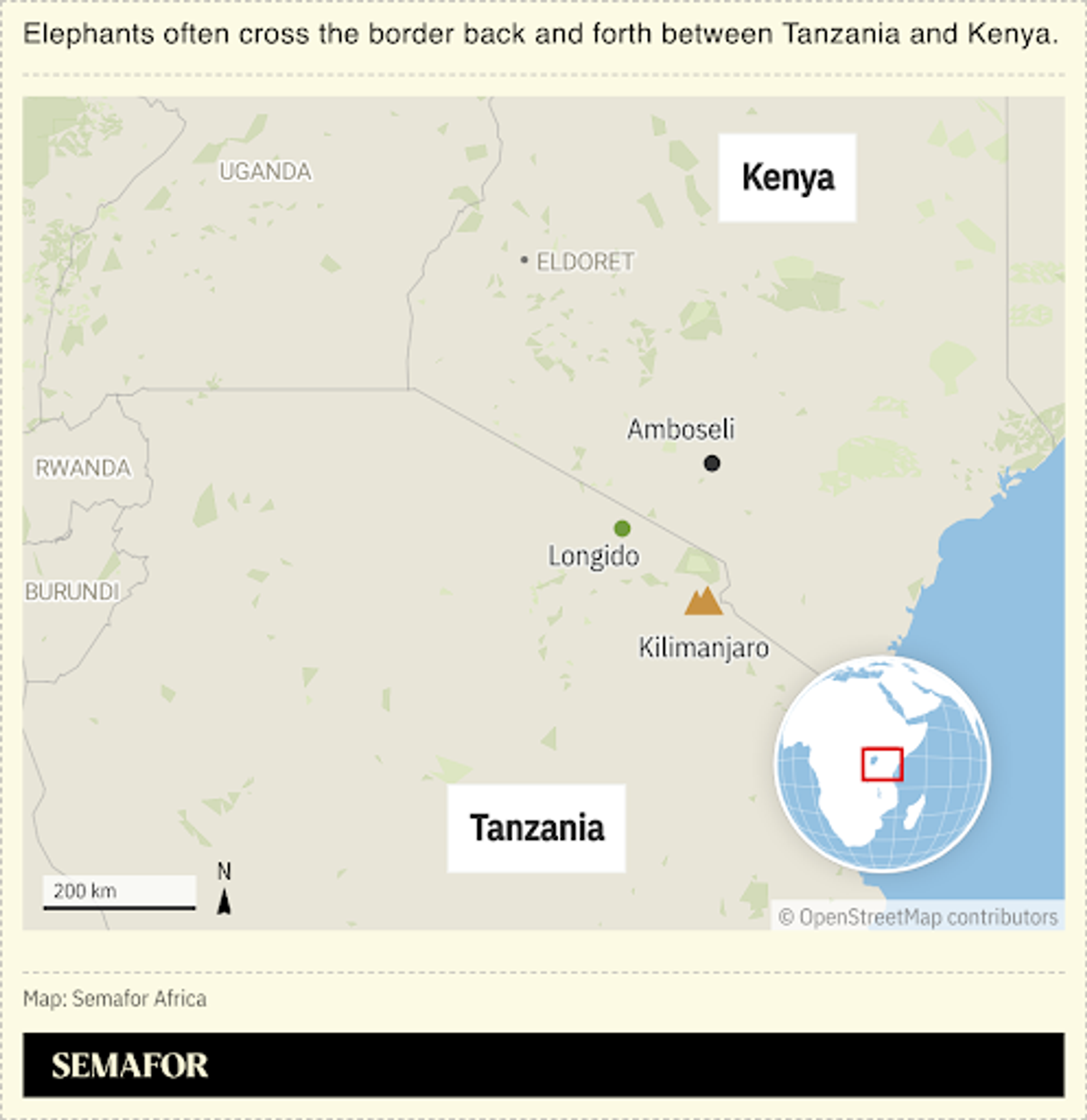

It’s “a myth,” said Farai Maguwu, founding director of the Centre for Natural Resource Governance, because it takes no account of the fact elephants roam freely between countries in the region.

Safari operators in Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, one of the areas earmarked for cullings, “are actually complaining about a declining number,” Maguwu said.

Elephants are not the problem, he argued, pointing to poor land management and the increase of human settlements next to national parks and in buffer zones designed to separate animals and people.

Conservationists are also concerned that killing these wild animals will push the delicate ecology of the two countries out of balance, making them even less resilient to drought.

It could also inadvertently increase human-elephant conflict, said Elisabeth Valerio, safari operator and conservationist in Hwange Park, Zimbabwe. The trauma of family members being killed can make elephants more aggressive, she told CNN.

Both Namibia and Zimbabwe say professional hunters will ensure entire groups are killed to prevent this.

Perhaps one of the biggest criticisms is that culls can’t do anything meaningful in the face of severe drought.

It’s a “false solution” when so many millions of people need food aid, Maguwu said. “A lot of us are hearing for the first time that elephant meat can be eaten,” he added, and expecting poor families to eat this meat is “an insult.”

The culls will do nothing to address hunger in anything but the most short-term way, said Megan Carr a senior researcher at the EMS Foundation, a South African social justice organization, calling them “misguided and cruel.”

Conservation biologist and natural resources consultant Keith Lindsay, also worries the culling could be used to push for a weakening of international rules on wildlife trading, such as selling ivory.

It could set up the narrative that “people who are opposed to wildlife trade, are opposed to starving people,” he told CNN.

A zebra at a waterhole in May 2015 at Halali in Etosha park in Namibia. Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images

Namibian government spokesperson Muyunda said many of the criticisms ignore the suffering the drought is causing to both people and animals.

There is hypocrisy, too, he added, as Western countries have also culled animals. “Just because it’s Namibia and it’s an African country, then the decision is questioned.”

Brown, from the Namibian Chamber of Environment, went further: “It’s actually a racist thing: ‘Africa, they can’t manage their wildlife. We need to tell them how they should do it.’”

But as fossil fuel pollution helps drive increasingly severe and devastating droughts, many conservationists fear these culls will open the door to much more extensive wild animal killings.

The government may start something which they won’t be able to finish,” Maguwu said. “Something that will go on and on.”