For California Salmon, Drought

And Warm Water Mean Trouble

With record drought and warming waters due to climate change, scientists are concerned that the future for Chinook salmon — a critical part of the state’s fishing industry — is in jeopardy in California.

by alastair bland

Gushing downpours finally arrived in California last month, when December rains brought some relief to a landscape parched after three years of severe drought.

But the rain came too late for thousands of Chinook salmon that spawned this summer and fall in the northern Central Valley. The Sacramento River, running lower than usual under the scorching sun, warmed into the low 60s — a temperature range that can be lethal to fertilized

Pacific Northwest National Lab

Chinook, the largest species of Pacific salmon, need cool waters to reproduce.

Chinook eggs. Millions were destroyed, and almost an entire year-class of both fall-run Chinook, the core of the state’s salmon fishing industry, and winter-run Chinook, an endangered species whose eggs incubate in the summer, was lost.

The disaster comes on the heels of a similar event the previous autumn. It is also reminiscent of ongoing troubles on northern California’s Klamath River, where diversion of water for agriculture has at times left thousands of adult Chinook — the largest species of Pacific salmon — struggling to survive in water too shallow and warm to spawn in.

Now, scientists — who are observing increasing human demand for water, genetic decline of hatchery-reared salmon, and climate change models predicting intensified droughts — are concerned that the Chinook salmon will be unable to tolerate future river conditions and will all but vanish from California’s landscape.

Robert Lackey, a professor of fisheries at Oregon State University, Corvallis, says that as the climate continues to warm, “salmon at the southern edge of their range will be the first to go.” Lackey doubts any

Historically huge salmon runs could be reduced to almost nothing before the end of the century.

Pacific salmon species will go fully extinct soon, and in Alaska, Russia, and other northern regions he expects populations to remain relatively strong. But farther south, where rising water temperatures will reach or exceed the limits of the salmon’s physiological tolerance, Lackey predicts historically huge runs will be reduced to almost nothing before the end of the century.

Just two centuries ago, as many as two million Chinook spawned in the Central Valley each year. The fish headed from the Pacific into San Francisco Bay, and at the confluence of the valley’s two big rivers, about half turned north into the Sacramento River system while the rest went south into the San Joaquin River, seeking the cool headwaters where they would lay and fertilize their eggs.

In this large valley — where the Mediterranean climate is friendly to desert-loving crops like pistachios, figs, and olives — salmon may seem out of place. Yet they thrived here. That’s because some of the highest mountains in North America flank the Central Valley — the Sierra Nevada along the eastern side and the Cascades at the north end. These ranges are buried in snow most winters, and through the summer and fall meltwater gushes into the lowlands below, providing the cold flows Chinook salmon require to successfully spawn.

The 19th-century flood of miners and settlers to California rapidly changed the ecosystem. Mining destroyed watersheds while overfishing dented the huge salmon runs. Then, in the 20th century, came the extensive systems of dams and canals built for agriculture. Reservoirs filled. So did the irrigation canals, and in the western San Joaquin Valley, a region naturally too arid to support intensive farming, vast orchards proliferated. The salmon fared poorly, though. The dams blocked the way to their historic spawning grounds and in some cases dried out rivers. In the San Joaquin, salmon vanished. On the Sacramento and its tributaries, populations hung on, though mostly because of artificial propagation in hatcheries.

Today, climate change is emerging as the next great threat to California’s remaining salmon runs. Peter Moyle, a fisheries biologist at the University

The mountain snowpack that has made life possible for salmon runs in California is expected to retreat.

of California, Davis, says the mountain snowpack that has made life possible for salmon runs in the state will retreat in the coming decades, as average temperatures escalate. Just a few spring-fed streams, he says, may remain cold enough year-round to support spawning.

This fall, scientists and environmentalists got a glimpse of what snowpack loss could mean for salmon statewide. Shasta Lake, its inflow from tributaries greatly diminished, dropped, while its waters warmed. Most years, even after a long, hot summer, cool water is available at the bottom of the reservoir, where an intake system draws the water through Shasta Dam and into the Sacramento River downstream. But by October of 2014, the water was 61 degrees, top to bottom, according to Jim Smith of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“There was no cold water available,” he says.

Tens — possibly hundreds — of thousands of salmon laid and fertilized their eggs through the autumn before any rain fell. “It would be a miracle if we had much survival in the river,” Moyle says.

Another autumn spawning disaster had occurred a year earlier, during the driest year in California’s recorded history. Government officials, hoping to ration reservoir water for later agricultural use, abruptly lowered the outflow from Shasta Lake in the midst of the largest spawning event the

California Dept. of Fish and Wildlife

Chinook salmon historically headed inland from the Pacific Ocean and up either the Sacramento or San Joaquin rivers to spawn.

Sacramento had seen in years. The river, teeming with 20-to-40-pound fish, shrank by half its volume. Thousands of salmon nests, or redds, were left high and dry.

Even the remote Klamath River, which flows into the sea just south of Oregon in a region of rain-drenched forest, is not immune to drought and thirsty farms. Last summer, the diversion of Klamath basin water to the Sacramento Valley, compounded by a year with virtually no rain, caused the dewatering of the Klamath during a large salmon run. Thousands of adult Chinook almost died in lukewarm water before the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, persuaded by Native American tribal leaders and environmentalists, reluctantly allowed more water to flow into the river, saving the fish. The action helped avoid a repeat of the kill in 2002, when sun-warmed waters caused a disease outbreak that killed roughly 34,000 adult fish.

The Klamath’s problems will get worse with climate change and increasing river temperatures, says Rebecca Quiñones, a U.C. Davis researcher who has extensively studied the Klamath ecosystem. “All the climate models show that the main stem of the [Klamath] river is going to be really

Some conservationists say hatchery production is making Chinook salmon more vulnerable to warming trends.

inhospitable to salmon,” Quiñones says.

Hatcheries in the Klamath and Sacramento basins produce most of the salmon that head out into the Pacific and are caught by fishermen off the California coast. But these facilities may now be causing more problems than they’re solving. For one thing, hatchery production is making Chinook salmon more vulnerable to warming trends, according to Jacob Katz, director of salmonid restoration initiatives with the group California Trout. He says hatcheries have traditionally harvested the very first salmon to swim through their processing rooms. In doing so, they have selected for a fall-run population that returns on the early end of the spawning season — exactly when waters may be warm and low, especially in the future.

Meanwhile, hatchery inbreeding and the elimination of natural selection is stripping the Chinook salmon genome of its evolutionary assets, Moyle says. The result is a domesticated animal not well suited to survive in a natural environment. Eventually, Moyle warns, hatchery fish will be so incompetent at finding food, evading predators, and finding their way back upriver to spawn that, even with tens of millions of them released each year, the Central Valley returns will diminish beyond hope. Hatcheries, without enough returning adults to provide sufficient eggs, will be forced to shut down. “This may take years, but the trajectory is there,” Moyle warns.

Today, in the Central Valley, juvenile salmon face multiple threats. In the Sacramento-San Joaquin delta, irrigation pumps draw the fish off their migration routes and into remote backwaters. Non-native bass and catfish, which are proliferating in the delta (and whose futures look bright in the warming waters), wait in ambush at reed clusters and pier pilings.

If rain falls at the right time, fast-moving torrents can wash the salmon safely out to sea; but in dry years, they drift slowly and precariously through the delta, and most perish before ever touching saltwater. Indeed, even critics of the hatcheries recognize that, were they to shut down, a fishing industry worth more than a billion dollars would collapse almost instantly.

Some scientists believe the Central Valley could still support a large, naturally spawning salmon population if the river system were restored to

Federal officials are considering a plan to trap adult salmon downstream and truck them upstream of Shasta Dam.

some semblance of its original state. Drained wetlands along the Sacramento River’s floodplains would need to be reconnected to the main channel, and dams would need to be operated to ensure that cold water always flowed downstream. In some cases, Moyle notes, dams could actually help salmon, since deep reservoirs would be the most reliable sources of cold water.

However, even outflow from the 500-foot depths of Shasta Lake will probably be too warm most years for endangered winter-run Chinook to spawn. To save this run from vanishing, the National Marine Fisheries Service is considering a long-term plan of trapping adult salmon downstream and trucking them upstream of Shasta Dam each winter so they can spawn where they did historically, in cool, high-elevation waters. The program — which Moyle calls a “desperation measure” — would also require trucking the juveniles back downstream in August.

Prospects for the Sacramento’s spring-run Chinook may be even worse. Most of the fish spawn in Butte Creek, a small tributary in the low hills just south of Mount Lassen. Each summer, this watershed is baked by the sun, and in the future, without reliable snowmelt from Lassen, successful spawning may not be possible here.

Along the West Coast of North America, the future for Chinook salmon looks bleak in the face of rising water temperatures. A study published in

ALSO FROM YALE e360

The Ambitious Restoration of

An Undammed Western River

With the dismantling of two dams on Washington state’s Elwha River, the world’s largest dam removal project is almost complete. Now, in one of the most extensive U.S. ecological restorations ever attempted, efforts are underway to revive one of the Pacific Northwest’s great salmon rivers.

READ MORE

December in the journal Nature Climate Change predicts that Chinook salmon will likely experience “catastrophic” population losses by 2100 due to warming river temperatures. Lackey says collective compromises in water use and lifestyle choices in the American West must be made before West Coast salmon, now reduced on average to less than five percent of their pre-Columbian numbers, can rebound. He doubts Americans are willing to pay this price. “Everywhere that we’ve seen economic development and [human] population growth, salmon runs have crashed,” Lackey says.

Moyle thinks that salmon could rebound, but only with the long-term cooperation of the water agencies that played a lead role in the loss of fish and habitat to begin with.

“California only has so much water available,” Moyle says. “Now, we are going to have to decide how we want to use our resources.”

http://e360.yale.edu/feature/for_california_salmon_drought_and_warm_water_mean_trouble/2834/

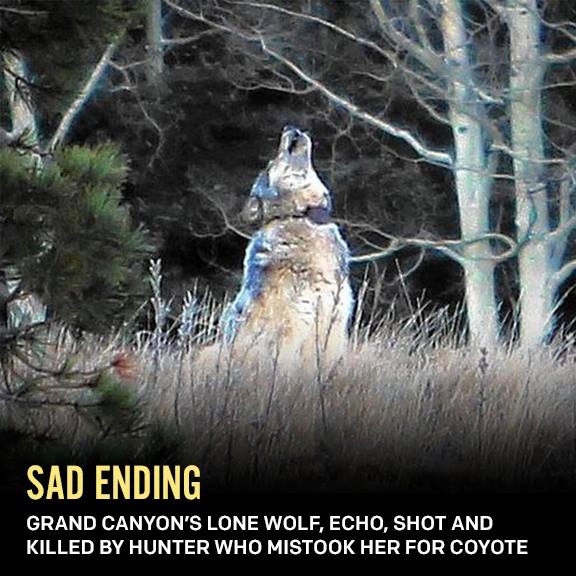

providing protections to wolves that are stronger than those found in the federal Endangered Species Act.

providing protections to wolves that are stronger than those found in the federal Endangered Species Act.