DECEMBER 14, 2020

by Max Telford, The Conversation

https://phys.org/news/2020-12-distant-animal-relative-sponge-jelly.html

The theory of evolution shows that all of life stems from a single root and that we are related, more or less distantly, to every other living thing on Earth. Our closest ancestors, as Charles Darwin recognized, are to be found among the great apes. But beyond this, confusion over the branching pattern of the tree of life means that things become less clear.

We know that life evolved from a common universal ancestor that gave rise to bacteria, archaea (other types of single-celled microorganisms) and eukaryotes (including multi-cellular creatures such as plants and animals). But what did the first animals look like? The past ten years have seen a particularly heated debate over this question. Now our new study, published in Science Advances, has come up with an answer.

Sponge vs comb jelly

From the 19th century to about ten years ago, there was general agreement that our most distant relatives are sponges. Sponges are so different from most animals that they were originally classified as members of the algae. However, genes and other features of modern sponges, such as the fact that they produce sperm cells, show that they certainly are animals. Their distinctness and simplicity certainly fit with the idea that the sponges came first.

But over the past decade, this model has been challenged by a number of studies comparing DNA from different animals. The alternative candidates for our most distant animal relatives are the comb jellies: beautiful, transparent, globe-shaped animals named after the shimmering comb-rows of cilia they beat to propel themselves through the water.

Comb jellies are superficially similar to jellyfish and, like them, are to be found floating in the sea. Comb jellies are undoubtedly pretty distant from humans, but, unlike the sponges, they share with us advanced features such as nerve cells, muscles and a gut. If comb jellies really are our most distant relatives, it implies that the ancestor of all animals also possessed these common features. More extraordinarily, if the first animals had these important characters then we have to assume that sponges once had them but eventually lost them.

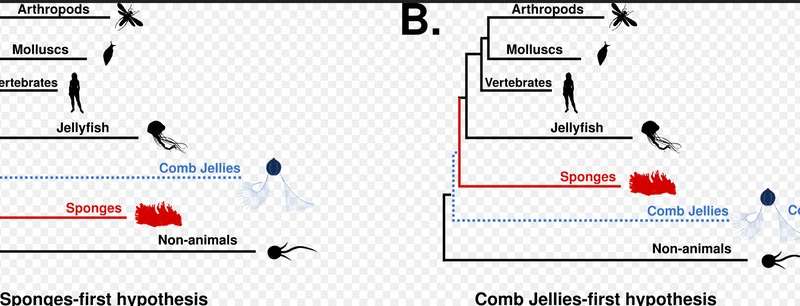

To understand how species evolved, scientists often use phylogenetic trees, in which the tips of the branches represent species. The points where branches split represent a common ancestor. The below image shows an example of a phylogenetic tree in which the sponge splits off first, and one in which the comb jelly splits off first.

Both the sponges-first and comb jellies-first evolutionary trees have been supported by different studies of genes, and the dispute seems to have resulted in a transatlantic stalemate, with most Europeans preferring the traditional sponges-first and the North Americans generally preferring the novel comb jellies-first.

The argument boils down to a question of how best to analyze the copious genetic data we now have available. One possibility put forward by the sponges-first supporters is that the animal tree that put comb jellies first is the result of an error. The problem occurs when one of the groups being studied has evolved much faster than the others. Fast evolving groups often look like they have been around for a long time. The comb jellies are one such group. Could the fast evolution of the comb jellies be misleading us into thinking they arose from an earlier split than they really did?

Are we being fooled by jellies?

We have approached this problem in a new way—directly investigating the possibility that the fast-evolving comb jellies are fooling us. We wanted to ask whether the unequal rates of evolution we see in these animals are likely to result in a wrong answer.

Our new way of working was to dissect the problem by simulating how DNA evolution happens using a computer. We started with a random synthetic DNA sequence representing an ancestral animal. In the computer, we let this sequence evolve, by accumulating mutations, under two different conditions—either in accordance with the sponge-first model or the comb jelly-first model. The sequences evolve according to the branching patterns of each tree.

We ended up with a set of species with DNA sequences that are related to one another in a way that reflects the trees they were evolved on. We then used each of these synthetic data sets to reconstruct an evolutionary tree.

We found that when we built trees using data simulated according to the comb jellies-first model, we could always easily correctly reconstruct the tree. That’s because the bias coming from their fast rate of change actually reinforced the information from the tree—in this case also showing they are the oldest branch. The fact that the tree information and the bias both point in the same direction guarantees we would get the right result. In short, if the comb jellies really were the first branch, then there would be no doubt about it.

When we simulated data with the sponges as the first branch, however, we very often reconstructed the wrong tree, with the comb jellies ending up as the first branch. This is clearly a more difficult tree to get right and the reason is that the tree information—in this case showing that the sponges are the oldest branch—is contradicted by the bias coming from the fast evolving comb jellies (which supports comb jellies-first).

The long branch leading to the comb jellies can indeed cause them to appear older than they really are and this difficulty reconstructing the tree is exactly what we encounter with real data.

So, who came first? The chances are that the genetic analyzes suggesting that comb jellies came first may in fact suffer from not accounting for the bias that makes these animals look older than they really are. In the end, our work suggests that the sponges really are our most distant animal relatives.

Explore furtherComb jellies make their own glowing compounds instead of getting them from food

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/85/78/8578258b-78dc-449c-ad11-991e20f92a3b/wolfdog.jpg)