Floodwaters from the Arkansas River line either side of a road in Russellville, Arkansas, engulfing businesses and vehicles.

Nathan Rott/NPR

Angel Portillo doesn’t think about climate change much. It’s not that he doesn’t care. He’s just got other things to worry about. Climate change seems so far away, so big.

Lately though, Portillo says he’s been thinking about it more often.

Standing on the banks of a swollen and surging Arkansas River, just upriver from a cluster of flooded businesses and homes, it’s easy to see why.

“Stuff like this,” he says, nodding at the frothy brown waters, “all of the tornadoes that have been happening – it just doesn’t seem like a coincidence, you know?”

A string of natural disasters has hit the central U.S. in recent weeks. Tornadoes have devastated communities, tearing up trees and homes. Record rainfall has prevented countless farmers in America’s breadbasket from planting crops. Rising rivers continue to flood fields, inundate homes and threaten aging levees from Iowa to Mississippi.

And while none of these events can be directly attributed to climate change, extreme rains are happening more frequently in many parts of the U.S. and that trend is expected to continue as the Earth continues to warm.

For many of the people living in the affected areas, the connection feels clear.

A group of friends look at the record-high Arkansas River in Fort Smith, Arkansas. “It’s part of history now,” says Savanna Bowling. “We had to come see it.”

Nathan Rott/NPR

“I think climate change is affecting the world right now and we should probably start doing something,” says Lucero Silva, watching the cresting river in Russellville, Arkansas.

“Somebody at my office told me, ‘We all owe Al Gore an apology,'” says Breigh Hardman, standing on a bridge over the Arkansas River in nearby Fort Smith. Gore’s 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth spurred both activism around global warming and opposition to it.

“It just tells us we got to come to a conclusion — not to get crazy — about global warming,” says Matt Breiner, watching the river further upstream near downtown Tulsa, Oklahoma.

NPR asked nearly two dozen people in Oklahoma and Arkansas who were experiencing the ongoing flooding about their thoughts on climate change. All of them said they believed that the climate was changing, even if they didn’t directly associate the raining and floods with it, or agree on the cause. (Six people said they believed God was driving the change.)

That aligns with recent polling by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University, which shows that more Americans are becoming concerned about global warming and believe in its existence, while a smaller majority understand that it’s mostly human-caused.

A follow-up report found that “directly experiencing climate change impacts” was the most common reason given by people who said they were becoming more concerned.

“Most studies do suggest that experiencing an extreme event does effect one’s beliefs about climate change,” says Elizabeth Albright, an assistant professor at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment.

Albright was part of a research team that surveyed communities impacted by heavy rains and flooding in Colorado in 2013. They found that people whose wider communities were significantly impacted were more likely to be concerned about climate change and the risk of future floods.

It’s an imperfect science though.

A study by the University of Exeter last year found thatpolitical identity and exposure to partisan news were more likely to influence people’s perceptions of some extreme weather events, as they relate to climate change.

“Efforts to connect extreme events with climate change may do more to rally those with liberal beliefs than convince those with more conservative views that humans are having an impact on the climate,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Ben Lyons, in a press statement.

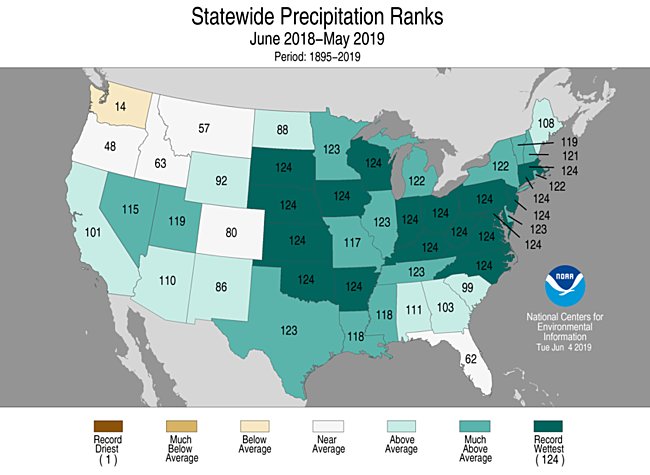

Flooding near Muskogee, Oklahoma, inundated businesses and homes. May was the second-wettest month in U.S. history, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Nathan Rott/NPR

Climate scientists and communicators in the largely conservative central Plains still see the ongoing flooding as an opportunity, though.

Marty Matlock, the executive director of the University of Arkansas Resiliency Center, works with rural and urban communities throughout the state and with the region’s massive agriculture industry.

“People are not questioning that things are changing,” he says. “The challenge is how do we motivate people, give [them] a sense that there is an actual opportunity for influencing that change in a positive way.”

Matlock believes that for too long climate scientists have been beating people “with the cudgel of information of science.”

“In a democratic society, if people don’t believe what you say, it doesn’t matter how right you are,” he says.

That doesn’t necessarily mean you need to convince people about the causes of climate change, he says. In some cases, it might be just as important to convince people and community leaders that they’ll need to adapt.

Extreme rains and flooding events are expected to be more common and more severe in America’s heartland, according to the most recent National Climate Assessment.

Joe Hurst, the mayor of Van Buren, Arkansas, a town of about 24,000 people on the Arkansas River, says there do seem to be indications that the climate is changing.

“I don’t know what causes it,” he says. “But all I know is that we’re dealing with a historic flood and now, in my mind, I’m going to be prepared for this unprecedented event to happen now more often.”

A pile of free sandbags in downtown Fort Smith, Arkansas. Volunteers filled them for homeowners and businesses trying to avoid the worst of the flooding.

Nathan Rott/NPR

Claire Heddles, Jennifer Ludden