While Congressional Democrats made clear that they would not bring the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to a vote until it had the backing of the AFL-CIO, support they finally secured last week, Democrats appear comfortable voting on the replacement trade deal that has virtually no support from leading environmental groups.

A House vote could come in the next few days and on Friday December 13, ten environmental organizations, representing 12 million members, sent a letter urging Congressional representatives to vote against the proposed deal, which will replace the 25-year-old North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

“This final deal poses very real threats to our climate and communities and ignores nearly all of the fundamental environmental fixes consistently outlined by the environmental community,” the letter stated. The groups — which include the Sierra Club, Greenpeace and 350.org — noted that “the deal does not even mention climate change, fails to adequately address toxic pollution, includes weak environmental standards and an even weaker enforcement mechanism, supports fossil fuels, and allows oil and gas corporations to challenge climate and environmental protections.” The groups link to a two-page analysis produced by the Sierra Club that goes into greater detail about what the group sees as the deal’s environmental shortcomings.

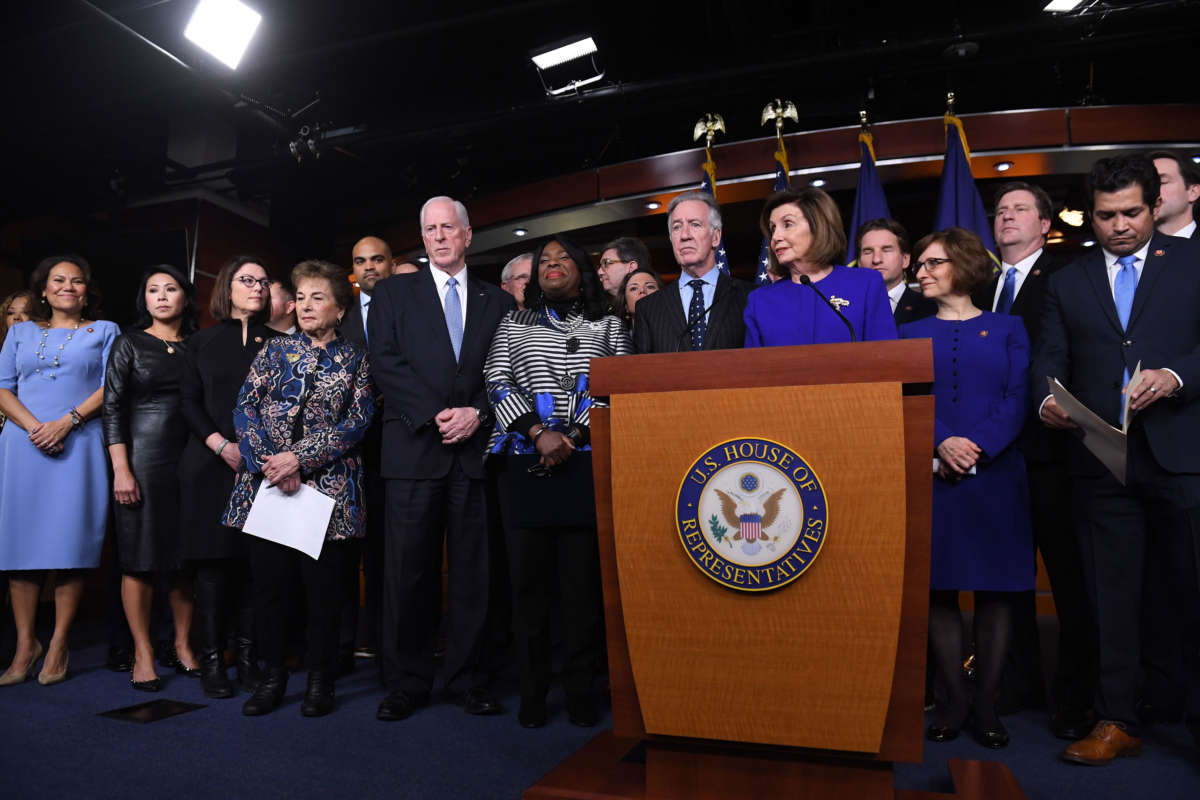

According to the environmental news organization E&E News, at a Politico event last week, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi described the USMCA as “substantially better” than NAFTA and said “we are very pleased with the environment [provisions].” While she conceded “we want more,” she stressed, “but we don’t have to do it all in that bill” and praised it for “talk[ing] about the environment in a very strong way.”

Rep. Suzanne Bonamici (D-Ore.), who co-led the House working group focused on environmental trade issues, told reporters at a press conference last week that “this is going to be the best trade agreement for the environment” and cheered its monitoring and enforcement provisions. Rep. Bonamici did not return In These Times’s request for comment.

Back in May, every Democrat on the House Ways and Means Committee, chaired by Rep. Richard Neal (D-Mass.), sent a letter to President Trump criticizing the draft agreement for its language around the environment, including its lack of “any apparent provisions directed at mitigating the effects of climate change.” Now the Committee is championing its work to shape the final text, saying the “revised version will serve as a model for future U.S. trade agreements.”

Having so many members of Congress support this agreement is especially frustrating for climate advocates because, in September, more than 110 House Democrats, including 18 full committee chairs, sent a letter to the president urging the new trade deal to “meaningfully address climate change” and to “include binding climate standards and be paired with a decision for the United States to remain in the Paris Climate Agreement.”

“While Democrats claim this deal improves on some environmental provisions, they have yet to explain how it meaningfully addresses climate change,” said Jake Schmidt, the managing director for the International Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

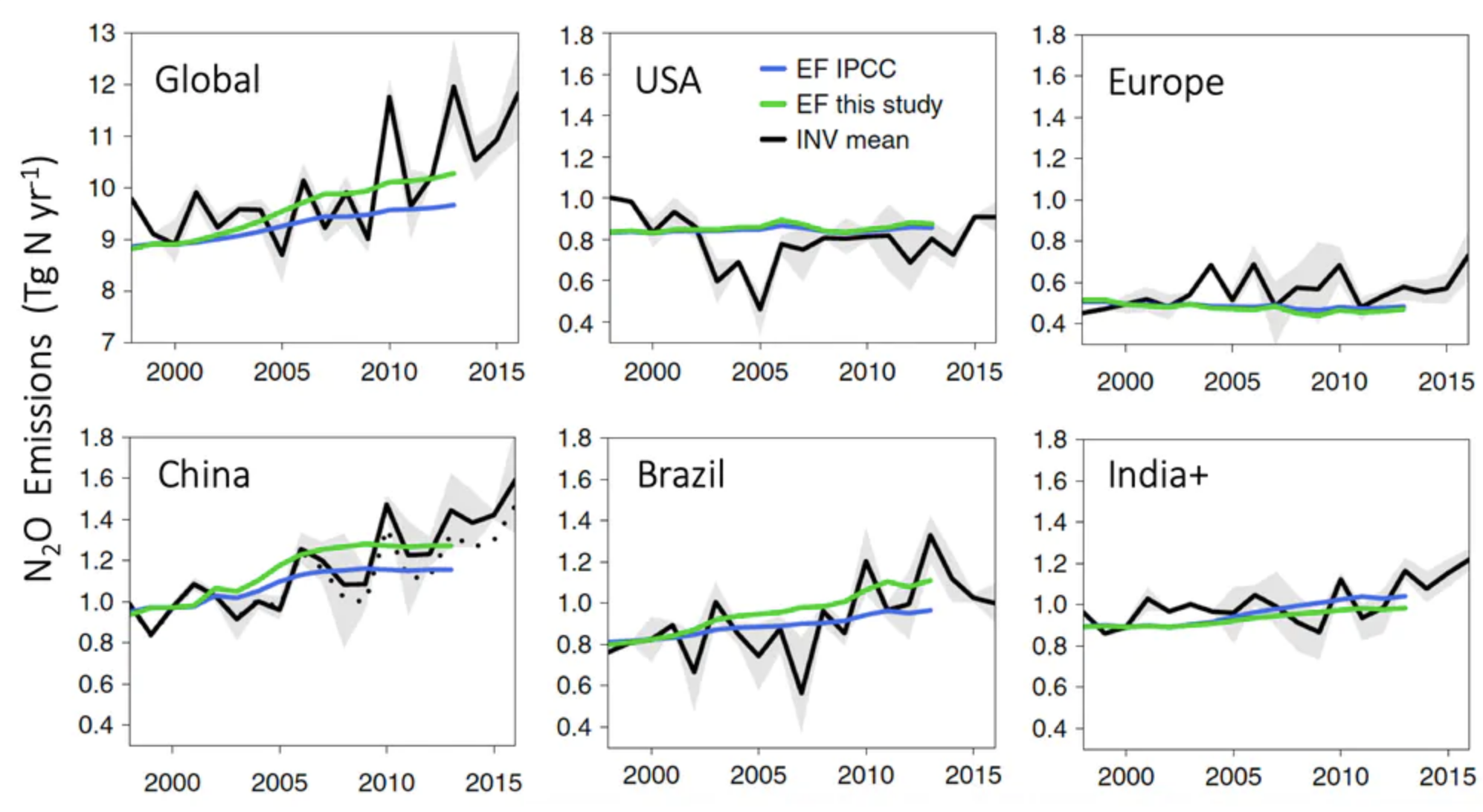

Climate advocates point to the growing problem of “outsourced” pollution — where wealthier countries like the United States and Japan take credit for improving their own domestic environmental standards, while then importing more goods from heavy-polluting countries. Critics say the current draft of USMCA does nothing meaningful to address this problem.

The trade agreement is being hailed for rolling back the Investor-State Dispute Settlement, controversial private tribunals that have enabled corporations to extract huge payments for government policies that may infringe on their profits. But Ben Beachy, a trade expert with the Sierra Club, says the agreement includes a major loophole for Mexico, where oil and gas companies will still be able to sue in those private tribunals.

“The approach the NAFTA 2.0 deal takes is recognizing there’s a problem but then allowing some of the worst offenders to perpetuate it,” he told In These Times. “It’s an unabashed handout to Exxon and Chevron: It’s like saying we’ll protect the hen house by keeping all animals out, except for foxes.”

Beachy says the deal overall “dramatically undercuts” the ability of the U.S. to tackle the climate crisis. “By failing to even mention climate change, it’ll help more corporations move to Mexico, and this is not a hypothetical concern,” he said. “We cannot simultaneously claim to fight climate change on one hand and enact climate-denying trade deals on the other. Do we really want to lock ourselves into a trade deal for another 25 years that encourages corporations to shift their pollution from one country to another?”

Karen Hansen-Kuhn, the program director at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, told In These Times the final agreement represents an even worse situation for farmers than under NAFTA. “On food and farm issues it’s definitely several steps back,” she said, pointing as an example to how USMCA will make it easier for companies to limit the information they provide to consumers about health and nutrition.

Emily Samsel, a spokesperson with the League of Conservation Voters (LCV), told In These Times that her organization informed members of Congress “that [they] are strongly considering scoring their USMCA vote when it comes to the House floor on LCV’s Congressional scorecard.” LCV was one of the ten environmental groups to sign the letter opposing the trade deal last week.

USMCA does include language requiring parties to adopt and implement seven multilateral environmental agreements, but the 2015 Paris Agreement is not among them. Getting the president to agree to putting anything about climate change or the Paris Agreement was always going to be a tough sell, considering Trump has promised to withdraw from the landmark climate pact. Still, environmental advocates insist House Democrats have real leverage that they should use more aggressively, particularly since getting the trade deal through Congress is Trump’s top legislative priority for 2019.

Democratic supporters of USMCA say the existing language is good enough for now, and that it will position the government well for when Trump is out of office. A spokesperson for Nancy Pelosi told The Washington Post that “the changes Democrats secured in USMCA put us on a firm footing for action when we have a President who brings us back into the Paris accord.” Earlier this year 228 House Democrats voted for a bill to keep the U.S. in the Paris Agreement.

U.S. labor groups have thus far remained mostly silent on the concerns raised by environmental organizations.

The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, which opposes the deal on labor grounds, did not return request for comment on the USMCA’s environmental provisions. The Communications Workers of America released a statement on Friday saying the deal includes some “modest improvements” for workers over NAFTA, but a spokesperson for the union told In These Times, “We don’t have any comment on the environmental provisions.” The BlueGreen Alliance, a national coalition which includes eight large labor unions and six influential environmental groups, has issued no statement on the trade deal, and did not return request for comment.

And the AFL-CIO issued a statement last week praising the deal, though noted “it alone is not a solution for outsourcing, inequality or climate change.” A spokesperson for the labor federation did not return request for comment.

(Thompson et al., Nature Climate Change, 2019)

(Thompson et al., Nature Climate Change, 2019)