An F/A-18 Super Hornet gets ready to fly off the USS Theodore Roosevelt in the Gulf of Alaska.

Zachariah Hughes/Alaska Public Media

The U.S. Navy is looking north.

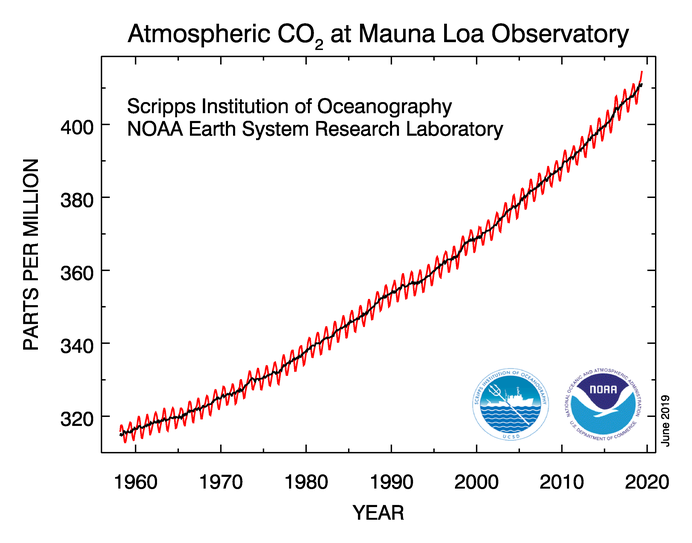

As climate change melts ice that has long blocked the region off from transit and industry, the military is figuring out how to expand its presence in the waters of the high north, primarily off the coast of Alaska.

Driving the push is that much of the commercial activity and development interest in the region is coming from nations that the Pentagon considers rivals, such as Russia and China.

The Navy’s presence in Alaska has waxed and waned over the years. The state has abundant Army and Air Force assets, with the Coast Guard spread throughout. The Navy runs submarine exercises beneath the sea ice off Alaska’s northern coast.

But until last year, no U.S. aircraft carrier had ventured above the Arctic Circle in almost three decades. The USS Harry S. Truman took part in naval exercises in the Norwegian Sea last October, the first such vessel to sail that far north since 1991.

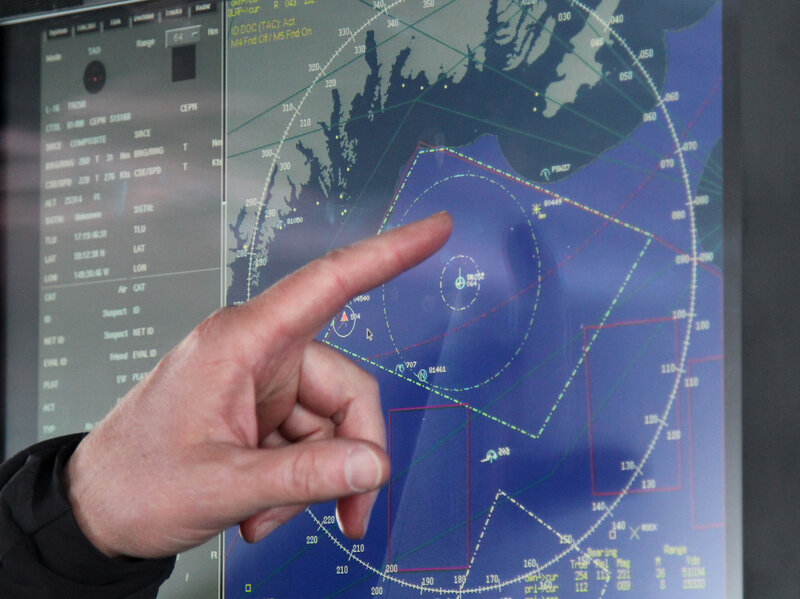

And for the first time in a decade, this May, an aircraft carrier strike group — led by the USS Theodore Roosevelt — sailed to Alaska as part of Northern Edge, a biennial large-scale military exercise that brings together personnel from all the military branches — airmen, Marines, soldiers, seamen and Coast Guardsman. The Navy always participates, but this year, it was out in force.

Lt. Cmdr. Alex Diaz oversees traffic on the USS Theodore Roosevelt flight deck.

Zachariah Hughes/Alaska Public Media

Rear Adm. Daniel Dwyer commands the nine ships in the Roosevelt strike group. Speaking on an observation deck several stories above the flight deck, he said climate change is adding a new urgency to training like this one as marine activity increases in Arctic waters.

“You see the shrinking of the polar ice cap, opening of sea lanes, more traffic through those areas,” Dwyer said. “It’s the Navy’s responsibility to protect America through those approaches.”

The Defense Department views the threat of military conflict in the Arctic as low, but it is alarmed by increasing activity in the region from Russia and China. A 2018 reportby the Government Accountability Office on the Navy’s role in the Arctic notes that abundant natural resources like gas, minerals and fish stocks are becoming more accessible as the polar ice cap melts, bringing “competing sovereignty claims.”

Defending U.S. interests in the Arctic

As the Roosevelt cruised through the Gulf of Alaska, F/A-18 Super Hornets took off and landed at a brisk clip. Each takeoff is a full-body experience for those on deck, shaking everything from one’s shoes to teeth. Planes are launched by a steam catapult system powered by the ship’s nuclear reactors.

Some of the jets flew more than 100 miles toward mainland Alaska and continued on past mountain ranges to sync up with Air Force and Marine Corps counterparts operating in the airspace around Eielson Air Force Base near Fairbanks. Then they returned to the Roosevelt. The whole trip lasts about four hours.

For the first time in a decade, an aircraft carrier strike group — led by the USS Theodore Roosevelt — sailed to Alaska as part of Northern Edge, a biennial large-scale military exercise.

Zachariah Hughes/Alaska Public Media

To land, the Super Hornets suddenly dropped out of the sky dangling a hook that snagged at wires bringing them from full speed to full stop in 183 feet. It looked less like a car braking and more like a roller coaster slamming still to give riders one last jolt.

“We are catching anywhere from six to 25 aircraft on this recovery,” crackled a voice over a loudspeaker on the deck. “I’m not sure yet [how many]. If they show up on the ball, we’re gonna catch ’em.”

The deck was coordinated chaos, with crew members and aircraft rotating through intricate maneuvers like a baroque ballet, billows of steam from the launch equipment periodically billowing past.

The deck crews are referred to as “skittles” because they wear uniforms that are color-coordinated to match their jobs. Much like the candy, most of the rainbow is represented. Greens take care of takeoffs and landings. Reds handle ordnance. Purples deal with fuel and are referred to as “grapes.”

The Navy says that given what is expected of it in the region, crews are trained and equipped to carry out their missions as well as any other nation’s navy.

“Regardless of the conditions: day, night, good weather, bad weather, flat seas, heavy seas, it’s the same procedure every time,” Dwyer said of the jets taking off below just as a helicopter set down on the flight deck.

A shifting focus to the “high north”

Speaking at this year’s Coast Guard Academy commencement, national security adviser John Bolton said the military will play a part “reasserting” American influence over the Arctic.

“We want the high north to be a region of low tension, where no country seeks to coerce others through military buildup or economic exploitation,” Bolton told graduates.

The Trump administration is expected to unveil a new Arctic strategy sometime this month.

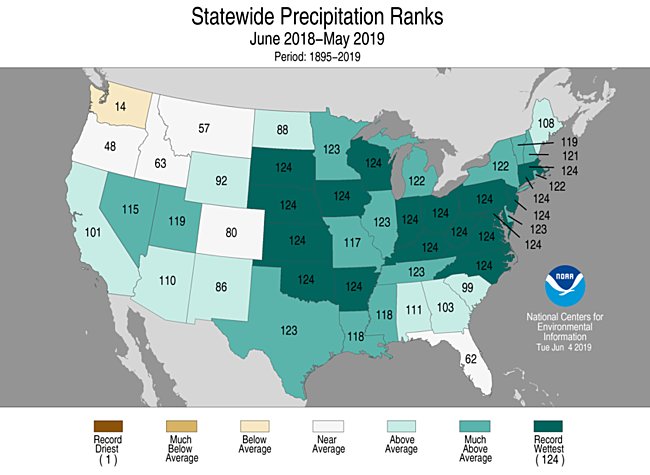

Forecasters anticipate diminishing ice will reliably open up northern sea lanes, thus cutting down the time and cost moving freight from Asia to Europe but causing a rise in vessel traffic.

The military is candid that the warming climate is opening up transit routes that sea ice has long locked in. Right now, though, the U.S. naval presence is minimal.

F/A-18 Super Hornet is launched by a steam-powered catapult off the USS Theodore Roosevelt during naval exercises in the Gulf of Alaska.

Zachariah Hughes/Alaska Public Media

“If you’re gonna be a neighbor, you have to be in the neighborhood,” said Vice Adm. John Alexander, commander of the Navy’s 3rd Fleet, which is responsible for the Northern Pacific, including the Bering Sea and Alaskan Arctic.

“We’re going to have to ensure that there’s free and open transit of those waters,” Alexander said.

But the Navy faces major impediments to expanding its presence in a maritime environment as harsh as the Arctic. According to the GAO report, most of the Navy’s surface ships aren’t “designed to operate in icy water.”

The authors note that Navy officials have stated that “contractor construction yards currently lack expertise in the design for construction of winterized, ice-capable surface combatant and amphibious warfare ships.”

After years of study, the Defense Department has yet to pick a location and design for a strategic port in the vicinity of the Arctic that can permanently accommodate a strong Navy presence.

And even if the military can operate in the Arctic, it still has to get there. For now, the region’s waters are solidly frozen over for much of the year. According to the Coast Guard, Russia has more than 40 icebreakers, including three new gargantuan nuclear-powered vessels designed to ply sea lanes along the northern sea route. The U.S. military, by contrast, has just two working icebreakers.

This story comes from American Homefront, a military and veterans reporting project from NPR and member stations.