Sign up to receive our latest reporting on climate change, energy and environmental justice, sent directly to your inbox. Subscribe here.

https://insideclimatenews.org/news/27072018/summer-2018-heat-wave-wildfires-climate-change-evidence-crops-flooding-deaths-records-broken

Earth’s global warming fever spiked to deadly new highs across the Northern Hemisphere this summer, and we’re feeling the results—extreme heat is now blamed for hundreds of deaths, droughts threaten food supplies, wildfires have raced through neighborhoods in the western United States, Greece and as far north as the Arctic Circle.

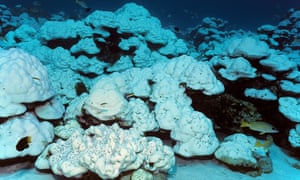

At sea, record and near-record warm oceans have sent soggy masses of air surging landward, fueling extreme rainfall and flooding in Japan and the eastern U.S. In Europe, the Baltic Sea is so warm that potentially toxic blue-green algae is spreading across its surface.

There shouldn’t be any doubt that some of the deadliest of this summer’s disasters—including flooding in Japan and wildfires in Greece—are fueled by weather extremes linked to global warming, said Corinne Le Quéré, director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia.

“We know very well that global warming is making heat waves longer, hotter and more frequent,” she said.

“The evidence from having extreme events around the world is really compelling. It’s very indicative that the global warming background is causing or at least contributing to these events,” she said.

The challenges created by global warming are becoming evident even in basic infrastructure, much of which was built on the assumption of a cooler climate. In these latest heat waves, railroad tracks have bent in the rising temperatures, airport runways have cracked, and power plants from France to Finland have had to power down because their cooling sources became too warm.

“We’re seeing that many things are not built to withstand the heat levels we are seeing now,” Le Quéré said.

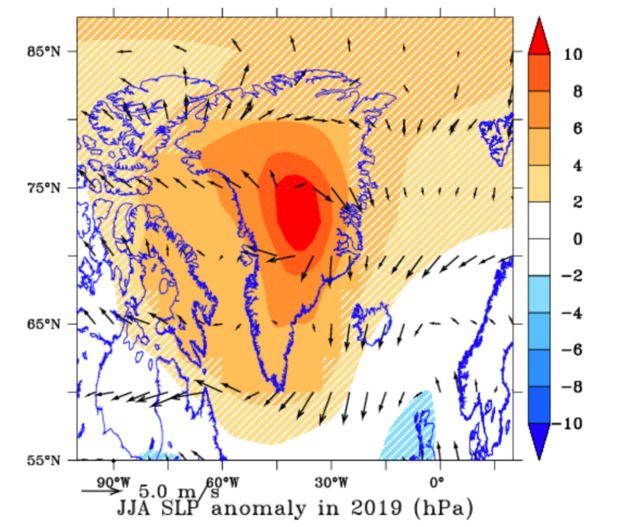

Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann said this summer’s extreme weather fits into a pattern he identified with other researchers in a studypublished last year. The jet stream‘s north-south meanders have been unusually stationary, leading to persistent heat waves and droughts in some areas and days of rain and flooding in others, he said. “Our work last year shows that this sort of pattern … has become more common because of human-caused climate change, and in particular, amplified Arctic warming.”

Deadly Heat Waves from Canada to Japan

There are many ways to define a heat wave, but the conditions in many areas of the planet this summer have been universally recognized as severe, said Boram Lee, a senior research scientist with the World Meteorological Organization.

“From around end of June, many countries in Europe, Asia and North America have issued severe warnings,” she said. The UK, U.S., Japan and Korea all had long-lasting warnings, and Japan declared the recent heat wave a natural disaster, she added.

In Europe, scientists on Friday released a real-time attribution study of the heat wave that has baked parts of northern Europe since June. They found that global warming caused by greenhouse gas pollution made the ongoing heat wave five times more likely in Denmark, and twice as likely in Ireland.

“Near the Arctic, it’s absolutely exceptional and unprecedented. This is a warning,” said French heat wave expert Robert Vautard, who worked on the study for World Weather Attribution. The group previously determined that global warming made last summer’s “Lucifer” heat wave in southern Europe 10 times more likely.

“In many places, people are preparing for the past or present climate. But this summer is the future,” he said.

The geographic scope and persistence of the European heat wave stands out. An area stretching from the British Isles to Eastern Europe and north to the Arctic is bright red on European heat wave and drought maps, covering an area about as big as Texas and California combined.

Crop damage is being reported in parts Norway through Sweden, Denmark and the Baltics. Depending on conditions during the next month, more widespread crop failures could raise global food prices.

In mid-July, temperatures reached all-time record highs above the Arctic Circle, around 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and hovered in the 80s for weeks at a time. In the Norwegian glacier area that Lars Holger Pilø studies, the average temperature has been 9 degrees Fahrenheit above average for the past 30 days.

“I have been working here since 2006, and we have snow records going back 60 years, and there’s nothing like what we’re seeing right now,” said Pilø, part of team of ice archaeologists who are measuring the snow and ice loss and recovering historic artifacts like arrowheads and skis that were buried for millennia.

“I’m watching with a mixture of excitement and dread. I try not to think too much about it and stick to what we do, which is rescuing the artifacts coming out of the warming. I call it dark archaeology,” he said. “I look at the ice and I think, dead man walking.”

Norwegian Meteorological Institute climate scientist Ketil Isaksen said the extreme situation in Scandinavia fits with the pattern of global warming.

“There are so many extremes now from all over the world. We’re seeing a very common pattern. For me this is a strong climate signal. Ice that’s several thousand years old, melting in the matter of just a few weeks,” he said.

Isaksen is finalizing some studies that find heat is penetrating between 30 and 50 meters deep into the ground through cracks in the rocky mountains around Norway’s fjords. Instead of just a thin skin of permafrost melting, those mountains could fall apart in large chunks when autumn rains start, threatening coastal communities with tsunamis.

“Now we have a new extreme this summer. This will probably affect slope stability, and we can expect mass movement events like debris flows and landslides in late summer,” he said.

He said the studies help define new geologic hazard areas with knowledge that some of the melted mountains will see wholesale slope failure when strong rains hit. Based on the information, emergency managers are developing new early warning systems.

The Increasing Influence of Global Warming

About the same time the Norwegian researchers were uncovering ancient tools in the Arctic tundra this summer, heat records were being set in many other parts of the world.

Temperatures in Algeria reached 124 degrees Fahrenheit, setting a record for the African continent. A few weeks earlier, a city in Oman is believed to have broken a global record when it went more than 24 hours with temperatures never falling below 108 degrees. Japan set a national record of 106 amid a heat wave that has been blamed for more than 80 deaths.

Regional western heat events are becoming so pronounced that some climate scientists see the current extremes in the U.S. as a climate inflection point, where the global warming signal stands out above the natural background of climate variability.

In mid-July, a week of temperatures in the high 80s and up to 96 degrees Fahrenheit in normally cool Quebec killed more than 50 people, and while that heat wave was waning, another was building in Asia, where the Japan Meteorological Agency said that 200 of its 927 stations topped the 35 degree Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit) on July 15. Since then, at least 80 people have died and thousands have gone to hospitals with heat-related ailments.

“There are irrefutable scientific evidences that climate change alters both the intensity and frequency of such extreme phenomena as heat waves, and ongoing efforts are dedicated to understand how big the impact of man-made climate change is,” said the WMO’s Boram Lee.

Across social media, climate scientists are responding with a collective “we warned about this,” posting links to 10 years’ worth of studies that have consistently been projecting increases in deadly heat waves. If anything, the warnings may have been understated.

“The rise in heat waves is stronger than many climate models project,” said World Weather Attribution’s Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, who measured a record high temperature outside his office in the Netherlands on July 26, then tweeted that global warming is making the heat there 20 times more likely than in 1900.

Wildfires Out of Control

Hot and dry weather also makes forests more flammable. In Greece, after a month of record and near-record heat, flames ran wild through the community of Mati on July 23, killing at least 80 people. On July 26, a blaze in Northern California jumped the Sacramento River and spawned fire tornadoes, forcing the evacuation of parts of Redding, a city of 92,000. And in Germany, residents of southern Berlin awoke Friday to the sight of smoke on the horizon, an event that will also become more common in that part of the world.

Although climate scientists are reluctant to link any one particular fire to climate change, there is plenty of scientific evidence showing how heat-trapping greenhouse gases contribute to increased fire danger.

“Weather is a product of the climate system. We are drastically altering that system, and all the weather we observe now is the product of that human-altered climate system. One result is an increase in the frequency, size and severity of large fire events,” University of California, Merced researcher Leroy Westerling wrote on Twitter.

University of Arizona climate researcher and geographer Kevin Anchukaitis publicized several wildfire studies from the last 10 years that all show how and why global warming is making fires bigger, more destructive and longer-lasting. “Is climate change the only factor influencing wildland fire? No, of course not—but climate change is influencing area burned and fuel aridity,” he wrote.

Tyndall Centre Director Le Quéré said she faulted some media for failing to connect global warming to the current global heat wave. “This signal is very clear,” she said, adding that some of the early stories about the deadly fire in Greece almost seemed to downplay a link to climate change.

On Friday, the WMO released a new statement highlighting the links between global warming and wildfires and reminding readers that “heat is drying out forests and making them more susceptible to burn.”

Extreme Rainfall and Flooding

There is also still reluctance to link individual extreme flood events with global warming, despite plenty of scientific evidence that today’s global atmosphere—1 degree Celsius warmer than 100 years ago—holds much more moisture that can be delivered by regional storm systems.

Those warnings were not enough to help the more than 200 people who died in Japan in late June amid a series of record-setting torrential rain storms. Regional weather patterns certainly played a role, but ocean currents and an atmosphere juiced up by global warming likely boosted moisture for the storm.

Two years ago, Alfred Wegener Institute climate researcher Hu Yang showed how climate change is strengthening ocean currents that carry moisture from the ocean toward Japan. The research showed the currents have been getting stronger and warmer in tandem with rising atmospheric CO2 levels. Eventually, that heat is released to the atmosphere during storms, as wind or rain or both.

Yang said his continuing research is finding similar evidence that a powerful current near Japan may be “a super hotspot under global warming.” As the current strengthens, it will release its energy as water vapor, fuel for storms that can cause extra heavy rains in Japan and other parts of Asia, he said.

In the U.S., June flooding in the Midwest fits a detected pattern of increasing extreme rainfalls in that region. And in late July, 10 million people in the East, from Pennsylvania to North Carolina, were under various types of flood warnings with soggy air sloshing from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean over the overheated Northeastern Atlantic toward the coast.

What Can We Do About It?

In some cases, the scientific warnings about global warming impacts have resonated. At least parts of Europe are better prepared for heat waves now than they were in 2003, when extreme heat killed up to 70,000 people, said Le Quéré.

More cities know what they need to do to protect vulnerable people in an extreme event, she said, but they lack the money to do things like building more cooling shelters, or cooling core urban areas with green spaces and ponds.

“Maybe this is an opportunity, in a grim way, to prepare for events that will be longer and hotter,” she said. “It’s not just a case of holding our breath for three weeks and saying ‘it’s soon winter.’ It’s a time to push and protect vulnerable people and infrastructure.”

To prepare for the new normal, people must act in the next five to 10 years, said environmental scientist Cara Augustenborg, chairperson of Friends of the Earth Europe.

“We have to consider how every new infrastructure, agricultural or development project from now on will be impacted by climate change. We need to look at planned retreat from coastlines and developing further inland, building infrastructure that is more resilient to the effects of climate change such as sea level rise and temperature extremes.

“We’ve had several years now where airport runways have melted on extremely hot days,” she continued. “That’s something we need to factor in to future construction as it’s a problem that won’t go away.”

Society also needs to think about food security, she said.

“That’s what I really lose sleep over,” she said. “Our available arable land is declining now as our global population is booming. It doesn’t take much in the way of extreme weather to have a major impact on food supplies.”

Listen to a conversation about the extreme heat and climate change with ICN Managing Editor John H. Cushman, Jr., at On Point.