Looking at the news on the subject lately, it would seem that the Pacific Coast is climate change central. Starting with the sad excuse for a snowpack last winter and the near total lack of rains since then that’s led to the current and ongoing drought, which in turn is contributing to the catastrophic fires across the West, it’s looking like Nature has set her sights on our part of the planet.

But the fact is, global warming is a worldwide problem. July has joined a dozen or more previous months in getting overall “hottest on record” nods—like it or not.

If you’ve been following this blog recently, you might have had your fill of Okanogan Complex fire updates, or general articles with anecdotes about the other changes to predictable patterns the Earth is undergoing thanks to Anthropogenic Climate Disruption (or simply, too many humans creating too many tons of carbon). And if you’re any kind of self-respecting misanthrope like me, you may be wondering why it all matters. Certainly not so any future generations of humans can enjoy this wonderful place in the cosmos.

No, there’s much more than just us that’s worthy of our concern in this climate change catastrophe.

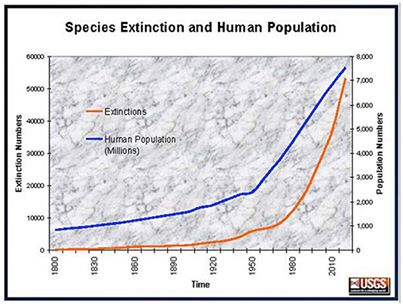

Global warming is about more than our comfort level or success. The harsh reality is that climate change is a major factor in the ongoing biodiversity emergency contributing to our current extinction spasm, namely The Sixth Great Mass Extinction–the one that we humans are causing and will more than likely be our undoing.

All of the West’s weather woes lead back to a blocking ridge of high pressure which is associated with the massive “blob” of warm water that’s been stuck for some time now off the West Coast and wreaking havoc with otherwise dependable patterns. A March 2008 interpretive handout from the USFWS, “Seabirds of the Pacific Northwest,” that I picked up at Haystack Rock, Cannon Beach, Oregon, actually does a surprisingly good job of spelling out the situation we’re in.

Changing Ocean Conditions

Weather is a major factor in sea bird success on the North Pacific coast. In productive breeding years, ocean winds cause an upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water which results in a plankton bloom. Plankton are the base of the food chain upon which larger fish and ultimately sea birds depend. In El Nino years the ocean warms which alters ocean currents and prevents upwelling. This results in a crash in prey populations causing large-scale breeding failure and adult mortality in sea birds.

Expected rises in ocean temperature due to global climate change may be similar in effect to El Nino events. However, unlike El Nino which is short-term natural phenomena that disrupts marine food webs periodically, global climate change represents a more pervasive and permanent change in the ecosystem, the consequences of which are unknown. In fact, climate change is often perceived to be a future threat, but the reality for our marine wildlife is that it is happening now and scientists are struggling to unravel the interrelationships within marine ecosystems to predict how those systems will respond.

I was going to title this post “Connecting the Dots on Climate Change,” but since this map only has one dot and it happens to be centered over “the blob” –climate change’s tie-in to everything that’s actively plaguing the West–I’ll let Canada’s The Weather Network explain it in excerpts from their article, “This weird ocean blob is linked to our worst weather. Here’s how”: Rodrigo Cokting Staff writer Wednesday, April 15, 2015

The devastating winter in Atlantic Canada, the drought in California and the lack of snow in many BC ski resorts all have one thing it common: The Blob, an unusually warm mass of water in the Pacific Ocean that stretches from Alaska to Mexico.

The Blob, past and present, plays a key role in extreme weather and disruptions to the natural world across North America during the past two years, and is likely to do so for another year at least.

Described first by University of Washington climate scientist Dr. Nicholas Bond, The Blob is a large body of water sitting off the west coast, stretching from the American state of Alaska all the way to Baja California, Mexico. This anomaly first appeared in the Pacific ocean during the winter of 2013 to 2014, about 800 kilometres off the coast and brought remarkably warm water to the region. Peak temperatures anomalies at one point were greater than 2.5C.

The Blob has since moved towards the coast and is connected to some of the biggest environment stories since the shift. Snow regularly appeared as rain on the west coast, leaving plenty of ski resorts wondering where all the snow went. Cities all across the Maritimes broke snowfall records in 2015 with places like Saint John, New Brunswick exceeding their previous record high by nearly 70 centimeters. California finds itself in the middle of the worst drought to affect the state in more than 100 years. Salmon are changing their natural pathways. Birds are showing up dead along both coasts. It’s at the point now where meteorologists consult its position and importance when compiling forecasts.

Scientists are taking a closer look at the extent that The Blob can affect the world. Meteorologists at The Weather Network have been factoring in the warm water since it first appeared in the Pacific.

“This phenomena was a very important consideration in developing our past several seasonal outlooks and it is a significant factor as we look at the upcoming summer,” The Weather Network’s Dr. Doug Gillham said. “[These new studies] identify a key variable that we used to make our predictions.”

But to understand the Blob, you need to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

“The actual wave pattern that causes the anomaly in the east originates in the equatorial pacific,” University of Washington’s Dennis Hartmann said. “It’s kind of like El Niño except in a different location. It’s characterized by a high pressure centre off the west coast of North America.”

Hartmann says that this pattern, often called pseudo-El Niño follows a large arc trajectory to affect North America, and has many consequences including the formation of the Blob.

The warmer water of The Blob, in turn, has a direct relationship with air temperatures and humidity levels over the nearby land, which contributed to the warm and dry winter that much of the West Coast saw the last couple of years.

“I’m confident this effect is extending to British Columbia,” he said. “It doesn’t make much of a difference in circulation patterns like wind but it does seem to impact the temperature and moisture properties over the area.”

The lack of moisture could have affected the wildfire season that plagued the northwestern parts of North America.

“When there are warmer winters the landscape dries out that much faster and the fire season becomes longer,” Bond said, explaining how the Blob could have had a secondary impact on the West Coast. “Oceans also affected humidity so conceivably it could have an effect on likelihood of thunderstorms but right now that’s just pure speculation.”

While the West Coast has had winter with above average temperatures, the East Coast suffered from the opposite problem.

“The pattern set up a weather dipole along North America. Cold and snow in the east while keeping things dry in the west,” Hartmann said. “The combination of the ridge to the west and through in the east pulled the cold air into places like Chicago.”

And it’s not just Canada feeling the consequences of the pattern. California has been going through a rough time, struggling to find water. Hartmann believes that recently, the drought may have a link to all these weather problems.

“This pattern contributed to the drought in California,” Hartmann said. “They’ve been having it for four years but the pattern made it worse during the last two years.”

But it’s not just people feeling the effect of the Blob. The anomaly is having troubling consequences on the wildlife according to Dr. Ian Perry, a research scientists with Fisheries & Oceans Canada.

“October and November saw some the highest water temps we’ve ever seen in certain locations along the B.C. coast. The temperatures in that warm body of water are about 3.5 to 4 degrees above normal. It’s the kind of temperature excursion we might statistically expect once every 400 years,” Perry said. “Coastal temperatures in some locations have been recorded since the 1930s and we’ve never seen some of these numbers.”

These warm waters have led to interesting changes in the wildlife including a redistribution of some species.

“The warm water has brought a lot of animals that we might usually see further south into B.C. and into Alaska,” Perry said. “We’ve seen albacore tuna as far up as into Alaska. Normally they might go as far north as Washington.”

The Pacific salmon has an even more peculiar behavior change due to the Blob. The species usually returns to the Fraser river in B.C. via one of two routes. Most of them come in through the southern part of Vancouver Island, swimming through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the international boundary between Canada and the United states.

But due to the warm water, the salmon are taking the longer route home swimming around northern B.C. and back down. The warm water is acting like a big plug and forcing the fish to bypass their preferred way back home.

“This has implications because we have a treaty with the U.S., that allows them to fish Pacific salmon. They get a certain amount of the catch because the normal route goes through the Strait of Juan de Fuca which is accessible to both U.S. and Canadian fishermen,” Perry said. “This time it’s been mostly Canadian fishermen that had access to the fish.”

If the Blob continues it could affect more than just swimming patterns. Perry says it could also lead to decreased populations in the following years.

“The salmon coming back spent much of their winter route in the north Pacific. They might come back a little bit skinnier but we don’t really expect major impact in the numbers,” Perry said. “The real question will be the fish going out in 2015. If these warm conditions stay along the coast, the juvenile salmon going out may starve and not survive well. There could be fewer salmon coming back in 2015, then 2016, then 2017.”

Warm water spells trouble for young salmon due to the difference in the zooplankton it contains,much smaller and less nutritious than the type that inhabits cold water.

“It’s the difference between having a roast beef dinner every night versus eating a stalk of celery every night,” Perry explained.

While we’ll have to wait and see if the salmon will be affected by the Blob, a bird commonly seen in B.C. is already suffering the devastating effect of the less nutritious water.

Cassin’s auklet is a small, chunky seabird that commonly breeds off the northern tip of Vancouver Island. After a successful breeding period during the spring of 2014, the birds have washing up dead all across the shore between Washington and Oregon at rates as high as 100 times the normal amount.

“It’s a combination of two things: the good breeding that happened in spring and the warm water that came toward the coast. A lot of these young birds were not familiar enough with how to find food in a different environment,” Perry said. “A lot of the birds that wash up ashore appear to be starving.”

It’s becoming clearer with every passing day that The Blob is going to have serious ramifications for as long as it stays in the ocean, and at least for now it seems to be comfortably parked off the west coast.

“It’s still there now and still pretty anomalous so the coastal weather and coastal biology will continue to be affected by that,” Hartmann said before adding that other conditions could mitigate the effect.

____________________

A pair of August 25, 2015 articles in the Daily Astorian hint to the dire straits we’re all in today:

Last fall, tens of thousands of the Cassin’s auklet, a small seabird, died. Parish said there was a correlation between warmer waters and a change in the distribution of food.

“We’re kind of hoping we don’t have another repeat season,” she said. “The North Pacific is pretty darn warm and has been for some time,” Parish said.

But there is usually upwelling, making it cooler along the coast and providing the common murre “a fair amount of food.”

Josh Saranpaa, assistant director of the Wildlife Center of the North Coast in Astoria, said the center has received about 12 birds a day over the past month, many from Cannon Beach. The majority, about 90 percent, are common murres.

“Every bird we’re seeing is starving to death,” he said. “It’s pretty bad.”

With warming ocean temperatures, fish are diving deeper than the birds can handle in some areas, he added.

The high number of starving adults along the North Coast, even experienced scavenger birds, indicates a “serious sign of a stressed ecosystem,” Parish said.

Saranpaa said seabirds are biological indicators, a way to check an environment’s health…

Richard Leakey, in his book, the Sixth Extinction: Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind, points out that, “marine regression” is associated with nearly all the previous mass extinctions. With warming, ocean acidification, jellyfish and toxic algae replacing plankton blooms throughout the areas, it’s starting to look like marine regression is happening here. Perhaps I should have titled this post, Mass Extinction: The future is now.

Stay tuned for Part 2