We seem indifferent to the mass extinction we’re causing, yet we lose a part of ourselves when another animal dies out.

Simon Worrall

for National Geographic http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/08/140820-extinction-crows-penguins-dinosaurs-asteroid-sydney-booktalk/

Published August 20, 2014

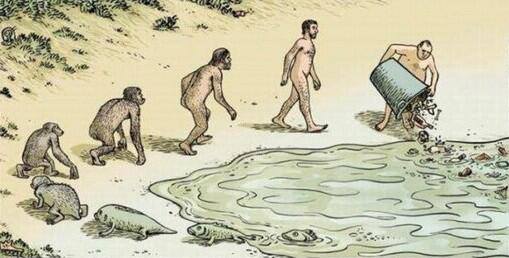

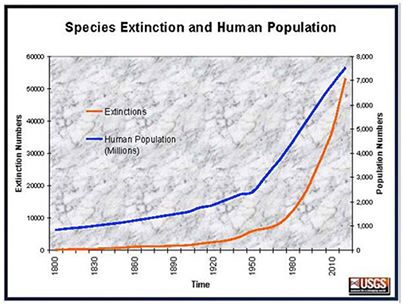

More species are becoming extinct today than at any time since dinosaurs were wiped off the face of the Earth by an asteroid 65 million years ago. Yet this bio-Armageddon, caused mainly by humans, is greeted by most of us with a yawn and a shrug. One fewer bat species? I’ve got my mortgage to pay! Another frog extinct? There are plenty more!

In his new book Australian anthropologist Thom Van Dooren tries to break through this wall of indifference by showing us how we’re connected to the living world, and how, when a species becomes extinct, we don’t just lose another number on a list. We lose part of ourselves.

Here he talks about grieving crows and urban penguins—and how vultures in India provide a free garbage-disposal service.

Your book is part of a new field of enquiry known as extinction studies. Can you give us a quick 101?

It’s an attempt to think about what role the humanities, and to some extent the social sciences, might play in engaging with the contemporary extinction crisis. In other words, how ethics, historical, and ethnographic perspectives can flesh out our notion of what extinction is and the way that different communities are differently bound up in extinction or potential solutions via conservation.

We live in a time of mass extinctions. How bad is it?

I think that it’s pretty widely accepted now that we’re living through the sixth massive extinction. The fifth one was 65 million years ago, when the dinosaurs vanished. Today we’re losing biodiversity at a similar rate. And this is, of course, an anthropogenic mass extinction. The primary cause is human communities.

But what we’re trying to do in extinction studies is to think about scale in different ways. How the loss of a species is not just the loss of some abstract collection of organisms that we can add to a list but contributes to an unraveling of cultural and social relationships that ripples out into the world in different ways.

You say that despite this, there is very little public outcry. Are people just too overwhelmed by the enormity of the crisis? Or what?

I think there are lots of answers to that question. For some people it probably is overwhelming. People have “mourning fatigue.” But I think for most people it’s just a genuine lack of awareness about the rates of biodiversity loss that we’re experiencing.

There’s an even more important answer to the question, though, which is that we haven’t found ways to really understand why it is that extinction matters. We can talk about numbers and the loss of a white rhino or a kakapo. But we haven’t developed the kind of story that we need to explain why it is that it matters—what is precious and unique about each of those species.

You have a wonderful phrase, “telling lively stories about extinction.” What does that mean?

I was trying to get at two things. One is to tell stories that make a committed stand for the living world. The other is to tell stories that are themselves lively, that will draw people in and arouse a sense of curiosity and accountability for disappearing ways of life, so they might contribute to making a difference. Stories are one way we make sense of the world and decide what it is that matters and what it is we will invest our time and energy in trying to hold on to and take care of.

Flight Ways differs from many other books in that it’s less interested in the phenomenon itself than in our moral and emotional responses to the crisis.

I have a background in philosophy and anthropology. So I’m more interested in how we understand and live with extinction. I started out wanting to write a book about extinction in general. But what I found doing fieldwork with scientists and communities bound up with the disappearing birds I describe is that each extinction event is totally different. There isn’t a single extinction tragedy. Each case is a unique kind of unraveling, a unique set of losses and consequences that need to be fleshed out and come to terms with.

Tell us about “urban penguins.”

One of the last colonies on mainland Australia, only about 60 or 65 breeding pairs, live in what is the biggest harbor in Australia, Sydney, my hometown. Some of them even nest under the ferry wharf, which many people don’t know as they catch the ferry in and out of the mainland. They’re beautiful little birds, about one foot [30 centimeters] tall, and they’ve been coming here as long as there have been historical records. Thanks to the dedication and work of conservationists and volunteer penguin wardens, who make sure the birds aren’t harassed at night or attacked by dogs and foxes, they’ve managed to hang on.

So that’s a hopeful story?

Yes, I think in many ways it is a hopeful story. For the most part we’ve been talking about extinctions that are caused by people. But in this case living in proximity with humans seems to be working.

One of your bugbears is what you call human exceptionalism. What is that?

This is a concept used by philosophers to describe an attitude where humans are set apart from the rest of the natural world. A little bit special, and so not like the other animal species.

The Lords of Creation?

Exactly. Rather than thinking of ourselves as an animal, we have a long history, in the West at least, of thinking of ourselves as either the sole bearers of an immortal soul or a creature that is set apart by its rationality and its ability to manipulate and control the world.

There are a whole lot of consequences that flow on from that kind of an orientation to the world. And some of them are very damaging for our species and for the wider environment. By diagnosing and analyzing human exceptionalism, we can try to fit humans back into the “community of life,” as the philosopher Val Plumwood called it.

Extinctions affect us in complex ways. Tell us about the Gyps vulture of India.

That’s a particularly interesting case, which drove home to me how extinction matters differently to different communities. The Parsi community in Mumbai have traditionally exposed their dead to vultures in “towers of silence,” as they’re called in English. Now the vultures are disappearing. Estimates suggest that 97 to 99 percent of the birds have gone in the last few decades. So the Parsi community is left in a very difficult position of trying to figure out how to appropriately and respectfully take care of their own dead in a world without vultures.

Vultures are great at garbage disposal, aren’t they?

[Laughs.] They certainly are! It’s estimated that they clean up five to ten million camel, cow, and buffalo carcasses a year in India. And that is obviously a free service. [Laughs.]

They’ve also played an important role in containing disease of various kinds and controlling the number of predators that feed on those carcasses and spread other diseases, like rats or dogs. The worry now is that the decline in vultures may lead to rises in the numbers of scavengers and in the incidence of diseases like rabies and anthrax in India.

You wrap the idea of the importance of mourning the loss of a species into a chapter about the Hawaiian crow. Do crows really grieve?

Yes, I think there’s very good evidence to suggest that crows and a number of other mammals grieve for their dead, and we don’t quite know how to make sense of that. In part this is bound up in those issues of human exceptionalism—the notion that grieving is something that only humans do. But it’s clear from observations of different species around the world that crows do mourn for other crows. They notice their deaths, and those deaths impact on them. So the chapter is a provocation to us to pay attention to all of the extinctions that are going on around us, to take up the challenge of learning from them in a way that, I hope, leads us to live differently in the world.

The Hawaiian crow is another good news story, isn’t it?

That’s right, thanks to really dedicated work by the Hawaiian state government, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the San Diego Zoo. They’ve been looking after these birds and breeding them in captivity for decades, and they now have over a hundred birds.

But what they need is somewhere for them to be released. They need good forest, and there’s not a lot of good forest left in Hawaii. Introduced species, like pigs and goats, have largely destroyed the understory of a lot of Hawaiian forest. There are plans to fence some of these areas and remove the ungulates, so that the forest might be restored. It’s a work in progress. But something a lot of people are dedicating a lot of time and energy towards achieving.

Your book is also a clarion call to action. You write, “We are called to account for nothing less than the entirety of life on the planet.” What can a regular Joe like me do?

That’s a tough question, which I struggle with all of the time. It’s one of the reasons that I write and tell stories. I love to do it. It’s also something that I find challenging, and I think might contribute in some way. So all that I can suggest to others is that they find ways of contributing, which they feel similarly passionate about and which might contribute, even in some small way. I don’t think change comes from singular, world-changing events. I think it’s built slowly, piece by piece, by people who are passionate about the world.

Read other interesting stories in National Geographic’s Book Talk series.

RELATED

—Species Extinction Happening 1,000 Times Faster Because of Humans?

—The Sixth Extinction: A Conversation with Elizabeth Kolbert

—Mass Extinctions: What Causes Animal Die-Offs?