Sunday, Jun 09 2019All CitiesChoose Your City‘Lake Baikal is contains more water than the five US great lakes combined’Mike Carter, The Observer, 2009By The Siberian Times reporter07 June 2019Sensational find of head of the beast with its brain intact, preserved since prehistoric times in permafrost.

The Pleistocene wolf’s head is 40cm long, so half of the whole body length of a modern wolf which varies from 66 to 86cm. Picture: Albert Protopopov

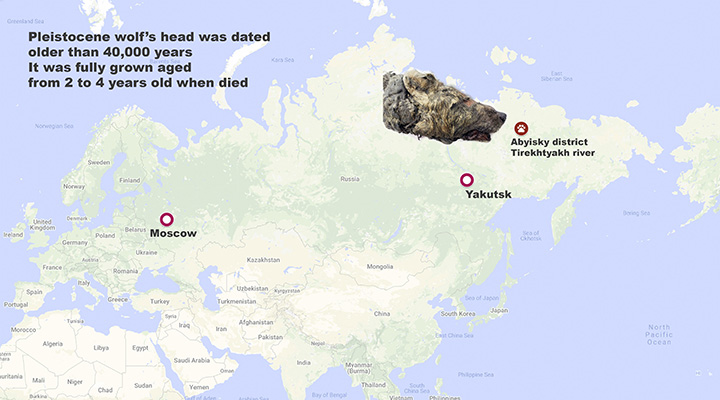

The severed head of the world’s first full-sized Pleistocene wolf was unearthed in the Abyisky district in the north of Yakutia.

Local man Pavel Efimov found it in summer 2018 on shore of the Tirekhtyakh River, tributary of Indigirka.

The wolf, whose rich mammoth-like fur and impressive fangs are still intact, was fully grown and aged from two to four years old when it died.

The wolf, whose rich mammoth-like fur and impressive fangs are still intact, was fully grown and aged from two to four years old when it died. Picture: Albert Protopopov

The head was dated older than 40,000 years by Japanese scientists.

Scientists at the Swedish Museum of Natural History will examine the Pleistocene predator’s DNA.

‘This is a unique discovery of the first ever remains of a fully grown Pleistocene wolf with its tissue preserved. We will be comparing it to modern-day wolves to understand how the species has evolved and to reconstruct its appearance,’ said an excited Albert Protopopov, from the Republic of Sakha Academy of Sciences.

Local man Pavel Efimov found it in summer 2018 on shore of the Tirekhtyakh River, tributary of Indigirka.

The Pleistocene wolf’s head is 40cm long, so half of the whole body length of a modern wolf which varies from 66 to 86cm.

The astonishing discovery was announced in Tokyo, Japan, during the opening of a grandiose Woolly Mammoth exhibition organised by Yakutian and Japanese scientists.

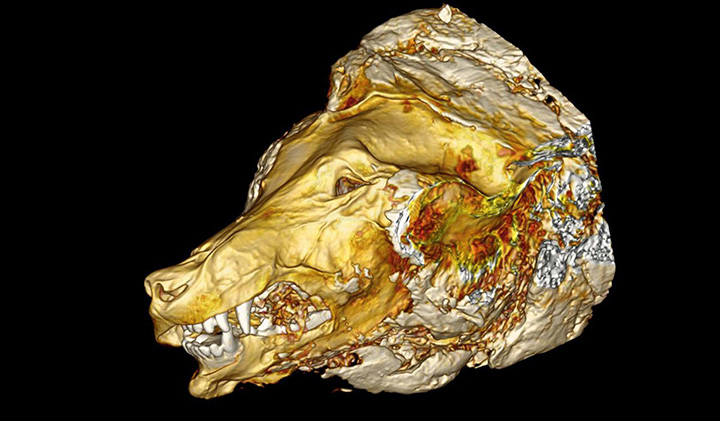

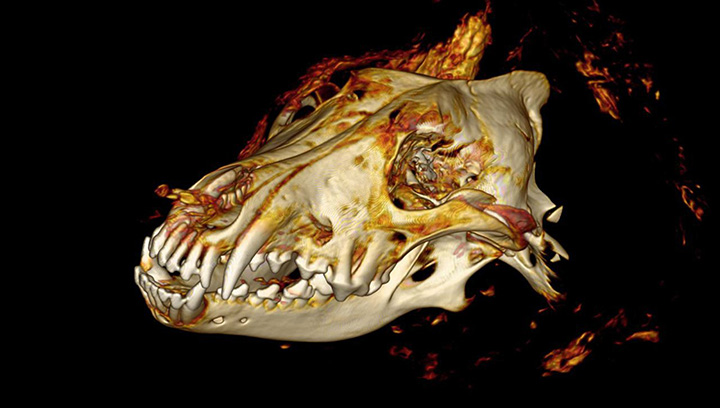

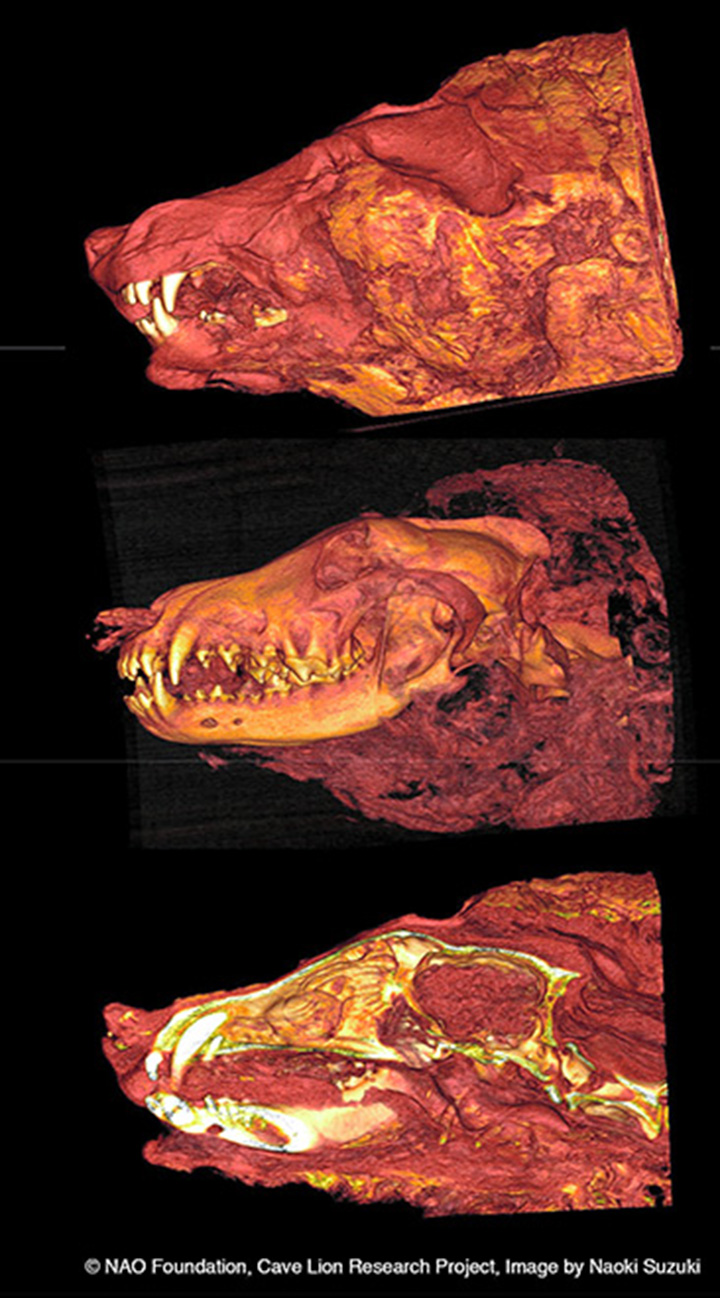

CT scan of the wolf’s head. Pictures: Albert Protopopov, Naoki Suzuki

Alongside the wolf the scientists presented an immaculately-well preserved cave lion cub.

‘Their muscles, organs and brains are in good condition,’ said Naoki Suzuki, a professor of palaeontology and medicine with the Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo, who studied the remains with a CT scanner.

‘We want to assess their physical capabilities and ecology by comparing them with the lions and wolves of today.’

‘This is a unique discovery of the first ever remains of a fully grown Pleistocene wolf with its tissue preserved.’ Pictures: Naoki Suzuki

Tag Archives: Pleistocene overkill

Fossilized footprints tell a story of how our ancestors hunted giant sloths

There’s plenty that archaeologists and paleontologists can learn from the bones and other artifacts left behind by ancient creatures and mankind’s own ancestors. Researchers can figure out what they looked like, where they lived, and who ate who, but painting a detailed picture of more advanced behavior is much more challenging. How ancient humans hunted, for example, is a huge topic of interest for many scientists, but evidence to support any theories is pretty rare.

A newly-discovered collection of fossilized footprints is giving researchers a rare glimpse into the past and helping them tell the story of how our ancestors once brought down a now-extinct creature that would have towered over them: the giant sloth.

The footprints, where were discovered at the White Sands National Monument, part of which is a US military testing ground. Today, the dry, barren location is a great place to test missiles without the risk of casualties, but 10,000 years ago it was the site of an epic battle between ancient humans and a massive ground sloth.

Giant sloths went extinct thousands of years ago, but at one time they were the target of human hunters. The reason for the species’ extinction is still debated, but some scientist blame overhunting as the cause. What these new footprints tell us for sure is that our ancestors seemed to have a pretty good idea of how to take them down, with circling footprints of multiple hunters surrounding one such sloth distracting it while others presumably attacked it with spears or other crude weapons.

“Geologically, the sloth and human trackways were made contemporaneously, and the sloth trackways show evidence of evasion and defensive behavior when associated with human tracks,” the researchers write in the study, published in Science Advances. “Behavioral inferences from these trackways indicate prey selection and suggest that humans were harassing, stalking, and/or hunting the now-extinct giant ground sloth in the terminal Pleistocene.”

Whether violent confrontations such as this were ultimately the cause of the giant sloth becoming extinct will likely never be conclusively proven, but the evidence that humans hunted these so-called “megafauna” on a large scale is mounting. Maybe that’s why modern animals are so darn small?

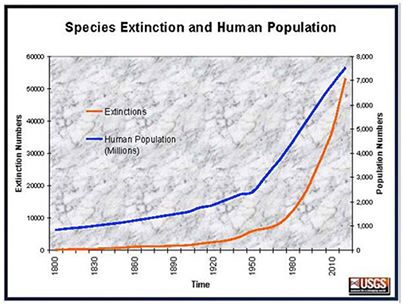

227,000 more people born every day!

Today’s my birthday. Big deal, huh? It may have seemed like a big deal for someone born in 1960, but nowadays, 227 HUNDRED THOUSAND people are born each and every day!

Here’s some light reading on overpopulation, for those who want to take a look at the bigger and bigger picture: http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/population_and_sustainability/

Human population growth and overconsumption are at the root of our most pressing environmental issues, including the species extinction crisis, habitat loss and climate change. To save wildlife and wild places, we use creative media and public outreach to raise awareness about runaway human population growth and unsustainable consumption — and their close link to the endangerment of other species.

There are more than 7 billion people on the planet, and we’re adding 227,000 more every day. The toll on wildlife is impossible to miss: Species are disappearing 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than the natural rate. It’s clear that these issues need to be addressed before it’s too late…

Humans have long history with causing extinctions

America’s Earliest Elmers Overhunted Elephants

Early Americans dined on four-tusked elephant relative, say scientists

Archaeologists have unearthed 13,400-year-old weapons crafted by the Clovis people mixed in with bones from an extinct elephant relative.

LiveScience Senior Writer July 15, 2014

-

A gomphothere jawbone as it was found in place, upside down, at the El Fin del Mundo site in Mexico. Vance Holliday/University of Arizona

A gomphothere jawbone as it was found in place, upside down, at the El Fin del Mundo site in Mexico. Vance Holliday/University of Arizona

There’s a new mega-mammal on the menu of America‘s first hunters.

On a ranch in northwestern Sonora, Mexico, archaeologists have discovered 13,400-year-old weapons mingled with bones from an extinct elephant relative called the gomphothere. The animal was smaller than mastodons and mammoths, but most had four sharp tusks for defense.

The new evidence puts the gomphothere in North America at the same time as a prehistoric group of paleo-Indians known as the Clovis culture, whose beautifully crafted projectile points helped bring down giant Ice Age mammals, including mammoths. This is the first time gomphothere fossils have been discovered with Clovis artifacts.

“The Clovis stereotypically went out and hunted mammoth, and now there’s another elephant on the menu,” said Vance Holliday, a co-author on the new study, published today (July 14) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Columbus Day: Humanists’ Holiday, Misanthropists’ Lament

No matter how you celebrate it, Columbus Day is a holiday for humanists. By “humanist,” I’m referring to “the concern with the needs, well-being, and interests of people.” Non-humans be damned, this holiday is a celebration of and for “people.”

Some who don’t like the moniker “Columbus Day,” (because of the implication that Columbus “discovered” the Americas and consequently set off the chain of events that led to the demise of the “native” Americans) want to see the name of the day changed to “Explorer’s Day,” or some such. The problem to us biocentrists is that any branching out and exploring of new territory by human beings, arguably the most destructive of all species ever unleashed on the planet, bar none—including the unwieldy dinosaurs—has resulted in the extinction or damn-near eradication of untold other incredible species.

Others want the name changed to “Native American Day,” conveniently ignoring the fact that the first Homo sapiens to make it over here (in their case, across the Bering Land Bridge), were big game hunters who followed their migratory prey species and laid waste to all the isolated, uncorrupted animals they could train a spear on. Animals like horses, camels, ground sloth and mastodon were victims of the “American Blitzkrieg,” the first stage of our ongoing anthropogenic mass extinction event.

No, to those of us who delight in the diversity of life on Earth and pine for the good old days, before the noxious spread of humanity, any day celebrating discovery for the species is a day of grief and sorrow, not festivity.

Homo sapiens is No Ordinary Species

When did big game hunters first start driving other species to extinction? If you go by the Young Earth Creationist’s calendar, even before the dawn of time. In this, the third installment of our series on detrimental denial, we’re going to look at how hunting by humans has been wiping out our fellow animal species since the earliest of times.

According to Richard Leaky and Roger Lewin, authors of The Sixth Extinction: Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind, “…In recent years it has become undeniable that the evolution of Homo sapiens was to imprint a ruinous signature on the rest of the world, perhaps from the beginning periods.”

In a chapter examining the sudden loss of North American mammals, such as elephants, mastodons, giant sloths, horses, camels and the American lions, paleoanthropologist Leaky and his co-author wrote: “Within a flicker of geological time, between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago, these animals were among some 57 similarly large mammal species to go extinct in North America while a much larger number did so in the southern continent.” In naming the culprit, Leaky went on to say that stone-aged peoples’ “…north to south population expansion left a trail of destruction, as hunters were easily able to kill large, lumbering prey unused to a new kind of predator. The animals probably had no innate fear of humans, as is often the case in regions of the world that have evolved in the absence of humans; they would therefore have been particularly vulnerable to efficient hunters.”

In the mid-1800s, Scottish geologist Sir Charles Lyle noted of the disappearance of so many North and South American megafauna, that human hunting “is the first idea presented to the mind of almost every naturalist.” But it wasn’t until 1911 that Alfred Russel Wallace, co-developer of the theory of evolution and natural selection, decided, “I’m convinced that the rapidity of…the extinction of so many large mammalia is actually due to man’s agency.”

Expounding on that concept, University of Arizona paleontologist Paul Martin in 1967 dubbed the over-kill hypothesis the “Pleistocene over-kill.” He noted that the megafaunal extinction phenomenon coincided exactly with the arrival of prolific human hunters armed with new technology: the Clovis spear-points, along with the spear thrower or Atlatl, which (like the “Chuck-it,” a popular kind of tennis ball thrower used in playing fetch with dogs inclined to retrieve) greatly increases throwing distance and accuracy.

Martin calculated that during their southward advance, human numbers could have grown to 600,000 within the 350 years it took them to reach the Gulf of Mexico and to many millions by the time they reached the southern tip of South America, within 1,000 years.

UCLA physiology professor and author, Jared Diamond, concurs with the Pleistocene overkill theory in his book, The Third Chimpanzee: the Evolution and Future of the Human Animal, “…the interpretation that seems most plausible to me, the outcome was a ‘blitzkrieg’ in which the beast were quickly exterminated—possible within a mere 10 years at any given site. If this view is correct, it would have been the most concentrated extinction of big animals since an asteroid collision knocked off the dinosaurs sixty-five million years ago. It would also have been the first of a series of blitzkriegs that marred our supposed Golden Age of environmental innocence and that have remained a human hallmark ever since.”

But the theory is not without its detractors, most notably those who blame climate change alone (the Earth was entering into a post-glacial period) as the driving force of that extinction event, and those who date the arrival of Paleo-Indians in the Americas much earlier.

Leaky addresses the latter with: “It is possible to imagine a series of migrations into North America when glaciation lowered sea levels sufficiently to expose the Bering land bridge that joins Alaska with Siberia. Pre-Clovis entry may have been sparse; in any case, the archaeological imprint implies that significant population growth did not result from them. Only with the coming of the Clovis people does the evidence suggest rapid population expansion, in numbers and in territory occupied. Whatever the date of the first entry, it does not detract from the overkill hypothesis linked to the end-Pleistocene expansion of the Clovis people.”

Clovis people.”

Meanwhile, Paul Martin addresses the climate issue with: “If ice age climate changes were important in determining the extinction of American large mammals, it is not obvious why earlier glaciations and interglacial warm-ups were unaccompanied by faunal losses.” But the case of the North American wooly mammoth may be the most damning of all to the climate-change-alone theory. An ice-age adapted species that disappeared from most of its range at the end of the Pleistocene epoch 10,000 years ago, isolated populations of the wooly mammoth were able to go on living on St. Paul Island, Alaska, up until just a few thousand years ago, roughly 3750 BC, and on Wrangel Island until 1650 BC—again, coinciding with the arrival of the first humans to those locations.

Contemporary researchers, such as John Guilday, suggest that the extinctions could be a result of a combination of the deadly impact of human hunting and a changing climate. As he put it, “In any event their combined effect was devastating, and the world is much the poorer.”

Like the global warming skeptic who isn’t comfortable placing blame on human activity for changing the Earth’s climate to the detriment all, the Pleistocene overkill denier has a hard time accepting that humans are responsible for diminishing biodiversity by hunting species to extinction. And some folks might wonder, ‘what’s the point of digging up the past, unearthing the dark side of primitive cultures that we’ve grown fond of thinking of as noble and beyond reproach?’ As Richard Leaky explains, “…human colonization of pristine lands is an extreme example of an invading species and the consequences of that invasion on existing [animal] communities. Mature, species-rich communities can often resist invasion attempts by most species. But Homo sapiens is no ordinary species, and its attempts at invasion are almost always successful and almost always devastating for the existing community. If we are to assess the impact that humans are having on the world today, we need a historical perspective.”

And Paul Martin adds, “The distinction between African and American Pleistocene extinctions is seen in the difference between gradually developing [humans] evolving for millions of years with large animals on one continent, compared with the onslaught of a highly advanced hunting society at the height of its power suddenly arriving on the other. Had America rather than the Old World been the center of human origins, the late Pleistocene record of extinction might well have been reversed.”

In other words, the overkill hypothesis is not meant to just pick on the Paleo-Indians, the Paleo-palefaces were cut of the same loin cloth. Unpopular as the subject may be, the only way to get to the root of the problem of human hunting is to cast off the Rousseauean fantasy that primitive hunting was somehow acceptable or harmonious. No other natural predator launched lethal projectiles from a distance or torched the landscape to drive entire herds of animals off cliffs.