Film Review and commentary by Jim Robertson

Spoiler Alert:

If you haven’t seen the movie, Life of Pi, and you plan to, don’t read this post yet. In discussing what I feel is the story’s theme I will end up revealing some of its major plot points, and I don’t want to spoil the experience just to make a point about ethical veganism…

…

Still here? Ok, assuming you’ve seen the film (or read the book on which it’s based), you’ll recall that there are essentially three parts to the story, ending with what many critics felt was a disappointing and even unnecessary “alternate” account of events to explain how Pi survived such a long ordeal at sea. Personally, I didn’t find the ending a disappointment, perhaps because I may have been one of the few people who got the message the movie was trying to make. After reading dozens of reviews fawning over the special effects (the computer generated middle act was indeed amazing) and decrying the ending, I found only one review that saw it the way I did: the “alternate” story (told by Pi to a pair of Japanese Ministry of Transport officials) was really what happened.

Now, you might be thinking, why does it matter; why ruin a fun thing (especially when it looked so astounding through 3-D glasses, so I hear)? To answer that, I’m going to try to make a long story short and hit its key points (many of which were completely missed by most mainstream film critics, and movie-goers).

The film starts off with an introductory act in which we learn about the early life of the main character, Pi, through a series of flashbacks as told to a visiting writer who wants to write his biography. We are told that Pi spent his childhood trying many of the world’s religions on for size, hoping to get to know God (his atheist father tells him, “You only need to convert to three more religions, Pi, and you’ll spend your life on holiday.”) At one point he jokes that as a Catholic Hindu, “We get to feel guilty before hundreds of gods, instead of just one.”

Of note is the fact that Pi is an ethical vegetarian. He’s also fascinated by a tiger (named Richard Parker, after its captor) stuck in a zoo owned by his father. When Pi is caught trying to befriend the captive tiger, his father decides to teach him a lesson by making him watch Richard Parker kill a goat, thus instilling a morbid fear of tigers in the curious boy.

The movie’s second act begins after it’s revealed that the zoo must close and the father decides to move the animals, and his family, by ocean-going freighter across the Pacific from India to Canada. En-route, the ship is swallowed up in a massive typhoon and Pi—according to the version of the story he is telling the writer, as we witness it—is the only human to make it onto a life raft. Somehow some of the zoo animals must have escaped their pens in the ship’s hold, and he finds himself adrift with only an injured zebra, an orangutan, a hyena and Richard Parker—the 500 pound Bengal tiger—for company.

It’s during this portion of the movie that viewers are drawn in by its startling special effects; and it’s also when the main character learns that sometimes the world is no life of pie (my interpretation of the title, as a play on the expression “easy as Pie”).

Driven by hunger, the hyena soon feeds on the zebra and, as it turns on the orangutan, Richard Parker rushes out from under the lifeboat’s only cover (where he has stayed out of sight until now) and quickly dispatches the hyena. This chain of events is essential to the plot since, skipping ahead to the third act, it mirrors Pi’s “alternate” story: substitute the zebra for a deckhand, the orangutan for his mother, the hyena for the cook and Richard Parker for Pi’s alter-ego.

The symbolism here is that after witnessing the cook kill his mother, Pi summons his tiger-inner-self to kill the cook. And eat him. That’s right, to survive his 227 days at sea, Pi had to turn to cannibalism. Incredibly, though it’s critical to the story’s theme, nearly none of the film reviews I read even mentioned cannibalism, since most critics didn’t realize that the second “alternative” version of Pi’s plight was what must have actually happened. I thought it was pretty obvious when an adult Pi asked the writer, “So which story do you prefer?” to which the writer answered: “The one with the tiger. That’s the better story.”And so it goes with God” was Pi’s reply, meaning that, people believe what they want to believe. In order to cope with the sometimes harsh realities of life and death, in this case, resorting to cannibalism for sustenance—and still retain one’s sanity—people often cling to a fantasy world and make up stories which are easier to stomach.

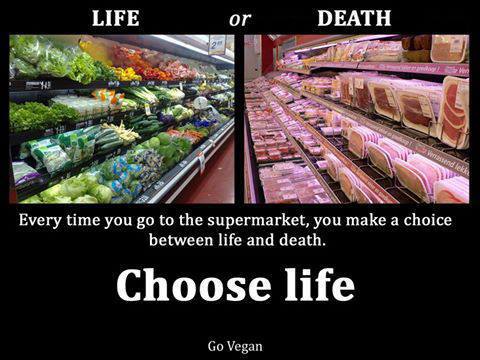

Life of Pi is more than just a happy little special-effects film about a vegetarian boy and a computer-generated, 3-D tiger surviving on computer-generated, 3-D tuna and flying fish. It’s about the kind of anguish any sane person would go through when forced to eat the flesh of another human being. Perhaps the reason I could more easily relate to the story’s deeper meaning (that so many carnivorous critics failed to see) is because, having eaten only plant-based food for the past decade and a half, I feel that same sick revulsion every time I pass the meat isle in the neighborhood grocery store and imagine people actually consuming the flesh so brazenly displayed there.