They’re more alike than not in their violations of moral common sense.

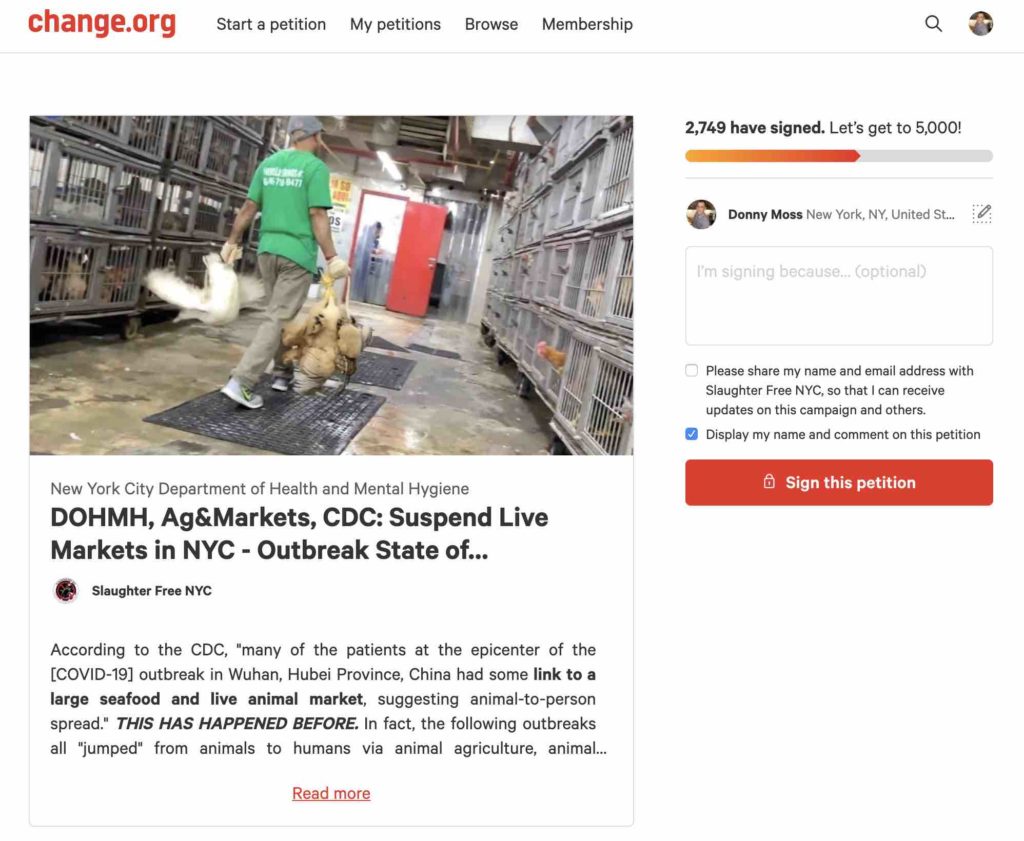

Although no government is better than China’s at making troublesome people disappear, a strange leniency has been accorded vendors at the country’s live-animal meat markets, who by most accounts gave us the pandemic and yet, reports the Daily Mail, have lately been allowed to set up shop again. China’s coronavirus lockdown is over, authorities have encouraged celebrations of “victory,” and citizens may once again go about their food shopping amid the cries and mayhem of animal slaughter. Ahh, back to normal life!In these parts, we’re told, you’re not really celebrating unless there’s bat, pangolin, cat, or dog meat on the table — the latter, notes the Daily Mail, “a traditional ‘warming’ winter dish.” Reporter George Knowles, writing late last month, provides one of the milder accounts of scenes that will quickly exhaust anyone’s supply of culturally sensitive euphemisms, describing one of the markets — also known as “wet markets,” where both live and dead animals are on offer — in China’s southwestern city of Guilin: “Terrified dogs and cats crammed into rusty cages. Bats and scorpions offered for sale as traditional medicine. Rabbits and ducks slaughtered and skinned side by side on a stone floor covered with blood, filth, and animal remains.”

If you’re up for a few further details, we have travel writer Paula Froelich, in a recent New York Post column, recalling how in the Asian live-animal markets she has visited the doomed creatures “stare back at you.” When their turn comes, she writes,

the animals that have not yet been dispatched by the butcher’s knife make desperate bids to escape by climbing on top of each other and flopping or jumping out of their containers (to no avail). At least in the wet areas [where marine creatures are sold], the animals don’t make a sound. The screams from mammals and fowl are unbearable and heartbreaking.

The People’s Republic has supposedly banned the exotic-meat trade, and one major city, Shenzhen, has proscribed dog and cat meat as well. In reality, observes a second Daily Mail correspondent, anonymously reporting from the city of Dongguan, “the markets have gone back to operating in exactly the same way as they did before coronavirus.” Nothing has changed, except in one feature: “The only difference is that security guards try to stop anyone taking pictures, which would never have happened before.”

Lest we hope too much for some post-pandemic stirring of conscience, consider the Chinese government’s idea of a palliative for those suffering from the coronavirus. As the crisis spread, apparently some fast-thinking experts in “traditional medicine” at China’s National Health Commission turned to an ancient remedy known as Tan Re Qing, adding it to their official list of recommended treatments. The potion consists chiefly of bile extracted from bears. The more fortunate of these bears are shot in the wild for use of their gallbladders. The others, across China and Southeast Asia, are captured and “farmed” by the thousands, in a process that involves their interminable, year-after-year confinement in fit-to-size cages, interrupted only by the agonies of having the bile drained. Do an image search on “bear bile farming” sometime when you’re ready to be reminded of what hellish animal torments only human stupidity, arrogance, and selfishness could devise.

If one abomination could yield an antidote for the consequences of another, Tan Re Qing would surely be just the thing to treat a virus loosed in the pathogenic filth and blood-spilling of Wuhan’s live market. There’s actually a synthetic alternative to the bile acids, but Tradition can be everything in these matters, and devotees insist that the substance must come from a bear, even as real medical science rates the whole concoction at somewhere between needless and worthless. President Xi Jinping has promoted such traditional medicines as a “treasure of Chinese civilization.” In this case, the keys to the treasure open small, squalid cages in dark rooms, where the suffering of innocent creatures goes completely disregarded. And perhaps right there, in the willfulness and hardness of heart of all such practices, is the source of the trouble that started in China.

Already, in the Western media, chronologies of the pandemic have taken to passing over details of the live-animal markets, which have caused viral outbreaks before and would all warrant proper judgment in any case. News coverage picks up the story with the Chinese government’s cover-up of early coronavirus cases and its silencing of the heroic Wuhan doctors and nurses who tried to warn us. To brush past the live markets in fear of seeming “xenophobic,” “racist,” or unduly judgmental of other people and other ways is, however, to lose sight of perhaps the most crucial fact of all. We don’t know the endpoint of this catastrophe, but we are pretty certain that its precise point of origin was what Dr. Anthony Fauci politely calls “that unusual human–animal interface” of the live markets, which he says should all be shut down immediately — presumably including the markets quietly tolerated in our own country. In other words, the plague began with savage cruelty to animals.

NOW WATCH: ‘Tesla Shuts Down California Factory’

Discussion of the live-animal markets is another of those points where moral common sense encounters the slavishly politically correct, though it’s not as if we’re dealing here with Asia’s most sensitive types anyway. No Western critic need worry about hurting the feelings or reputations of people who maximize the pain and stress of dogs in the belief that this freshens the flavor of the meat, and who then kill them at the market as the other dogs watch. Customers of such people aren’t likely to feel the sting of our disapproval either.

About the many customers and suppliers in Asia, and especially in China, of exotic fare, endless ancient remedies, and carvings and trinkets made of ivory, the best that can be said is that these men and women are no more representative of their nations than are the riffraff running the meat markets. Their demands and appetites have caused a merciless pillaging of wildlife across the earth — everything that moves a “living resource,” no creature rare or stealthy enough to escape their gluttony or vanity. Of late even donkeys, such peaceable and unoffending creatures, have been rounded up by the millions in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America for shipment and slaughter, all to satisfy demand for yet another of China’s traditional-medicine manias.

Easy to blame for all of this is the government of China. Authorities took forever, for example, to enforce prohibitions on ivory carving, despite an unquestioned competence in carrying out swift crackdowns. And in general, at every level, the government tends to tolerate a culture of cruelty, or else to actively promote it at the prodding of lucrative industries, both legal and illicit. But the problem runs deeper than that, even as many younger Chinese, to their enormous credit, have tried to organize against the ivory trade, the wet markets, and other depravities in their midst.

In the treatment of animals and in safeguarding human health, there are elementary standards to which all must answer. The challenge to clear thinking, as Melissa Chen writes in Spectator USA,

is to avoid falling into the trap of cultural relativism. It’s perfectly appropriate to criticize China’s rampant consumption of exotic animals, lack of hygiene standards and otherwise risky behavior that puts people at risk for zoonotic infections. Until these entrenched behaviors based on cultural or magical beliefs are divorced from Chinese culture, wet wildlife markets will linger as time-bombs ready to set off the next pandemic.

Acknowledging that Western societies have every moral reason to condemn the barbarism and recklessness of the live-animal markets only invites, however, a tougher question: Do we have the moral standing? And if any of us are guilty of blind cultural prejudice or of a smug sense of superiority toward Chinese practices, a moment’s serious thought will quickly set us straight.

When the Daily Mail describes how Chinese guards at the live-animal market now “try to stop anyone from taking pictures,” who does that remind us of? How about our own livestock companies, whose entire mode of operation these days is systematic concealment by efforts to criminalize the taking of pictures in or around their factory farms and slaughterhouses? The foulest live-animal-market slayer in China, Vietnam, Laos, or elsewhere would be entitled to ask what our big corporations are afraid the public might see in photographic evidence, or what’s really the difference between his trade and theirs except walls, machinery, and public-relations departments.

If you watch online videos of the wet markets, likewise, it’s striking how the meat shoppers just go on browsing, haggling, chatting, and even laughing, some with their children along. Were it not for the horrors and whimpers in the background, the scene could be a pleasant morning at anyone’s local farmer’s market. As the camera follows them from counter to counter, you keep thinking What’s wrong with these people? — except that it’s not so easy, rationally, to find comparisons that work in our favor.

No, we in the Western world don’t get involved while grim-faced primitives execute and skin animals for meat. We have companies with people of similar temperament to handle everything for us. And there’s none of that “staring back” that the Post’s Paula Froelich describes, because, in general, we keep the sadness and desperation of those creatures as deeply suppressed from conscious thought as possible. An etiquette of denial pushes the subject away, leaving it all for others to bear. Addressing a shareholders’ meeting of Tyson Foods in 2006, one worker from a slaughterhouse in Sioux City, Iowa, unburdened himself: “The worst thing, worse than the physical danger, is the emotional toll. Pigs down on the kill floor have come up and nuzzled me like a puppy. Two minutes later I had to kill them — beat them to death with a pipe. I can’t care.”

Following the only consistent rule in both live-animal markets and industrial livestock agriculture — that the most basic animal needs are always to be subordinated to the most trivial human desires — this process yields the meats that people crave so much, old favorites like bacon, veal, steak, and lamb that customers must have, no matter how these are obtained. When the pleasures of food become an inordinate desire, forcing demands without need or limit and regardless of the moral consequences, there’s a word for that, and the fault is always easier to see in foreigners with more free-roaming tastes in flesh. But listen carefully to how these foods or other accustomed fare are spoken of in our culture, and the mindset of certain Asians — those ravenous, inflexible folks who will let nothing hinder their next serving of pangolin scales or winter dish of dog — no longer seems a world away.

We in the West don’t eat pangolins, turtles, civets, peacocks, monkeys, horses, foxes, and wolf cubs — that’s all a plus. But for the animals we do eat, we have sprawling, toxic, industrial “mass-confinement” farms that look like concentration camps. National “herds” and “flocks” that all would expire in their misery but for a massive use of antibiotics, among other techniques, to maintain their existence amid squalor and disease — an infectious “time bomb” closer to home as bacterial and viral pathogens gain in resistance. And a whole array of other standard practices like the “intensive confinement” of pigs, in gestation cages that look borrowed from Asia’s bear-bile farms; the bulldozing of lame “downer cows”; and “maceration” of unwanted chicks, billions routinely tossed into grinders. All of which leave us very badly compromised as any model in the decent treatment of animals.

Such influence as we have, in fact, is usually nothing to be proud of. It made for a perfect partnership when, for instance, one of the most disreputable of all our factory-farming companies, Smithfield Foods, was acquired in 2013 by a Chinese firm, in keeping with some state-run, five-year plan of the People’s Republic to refine agricultural techniques and drive up meat production. Now, thanks to American innovation, Smithfield-style, the Chinese can be just as rotten to farm animals as we are — and just as sickly from buying into the worst elements of the Western diet.

In China and Southeast Asia, they have still not received our divine revelation in the West that human beings shall not eat or inflict extreme abuse on dogs but that all atrocities to pigs are as nothing. They’re moving in our culinary direction, however, and more than half the world’s factory-farmed pigs are now in China and neighboring countries. In the swine-fever contagion spreading across that region right now — addressed as usual by mass cullings: gassing tens of millions of pigs or burying them alive — our industrial animal-agriculture system is leaving its mark, while providing yet further evidence that factory farms are all pandemic risks themselves.

How many diseases, cullings, burial pits, and bans on photographing these places even at their wretched best will we need before realizing that the entire system is profoundly in error, at times even wicked, and that nothing good can ever come of it? Perhaps the live-animal markets of China, with all the danger and ruin they have spread, will help us to see those awful scenes as what they are, just variants of unnatural, unnecessary, and unworthy practices that every society and culture would be better off without.

Plagues, as we’re all discovering, have a way of prompting us to take stock of our lives and to remember what really matters. If, while we’re at, we begin to feel in this time of confinement and fear a little more regard for the lives of animals, a little more compassion, that would be at least one good sign for a post-pandemic world.