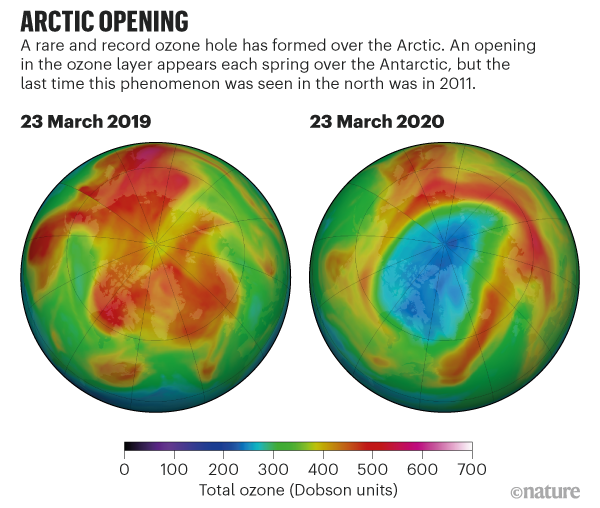

A vast ozone hole — likely the biggest on record in the north — has opened in the skies above the Arctic. It rivals the better-known Antarctic ozone hole that forms in the southern hemisphere each year.

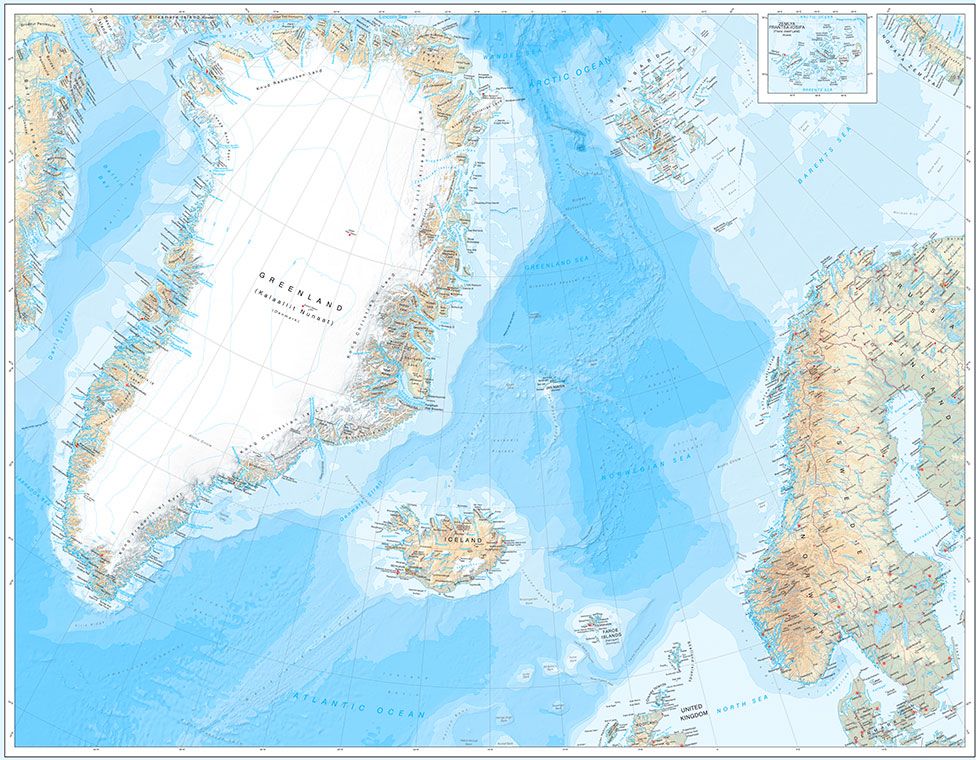

Record-low ozone levels currently stretch across much of the central Arctic, covering an area about three times the size of Greenland (see ‘Arctic opening’). The hole doesn’t threaten people’s health, and will probably break apart in the coming weeks. But it is an extraordinary atmospheric phenomenon that will go down in the record books.

“From my point of view, this is the first time you can speak about a real ozone hole in the Arctic,” says Martin Dameris, an atmospheric scientist at the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen.

Source: NASA Ozone Watch

The hole’s formation

Ozone normally forms a protective blanket in the stratosphere, about 10 to 50 kilometres above the ground, where it shields life from solar ultraviolet radiation. But each year in the Antarctic winter, frigid temperatures allow high-altitude clouds to coalesce above the South Pole. Chemicals, including chlorine and bromine, which come from refrigerants and other industrial sources, trigger reactions on the surfaces of those clouds that chew away at the ozone layer.

The Antarctic ozone hole forms every year because winter temperatures in the area routinely plummet, allowing the high-altitude clouds to form. These conditions are much rarer in the Arctic, which has more variable temperatures and isn’t usually primed for ozone depletion, says Jens-Uwe Grooß, an atmospheric scientist at the Juelich Research Centre in Germany.

But this year, powerful westerly winds flowed around the North Pole and trapped cold air within a ‘polar vortex’. There was more cold air above the Arctic than in any winter recorded since 1979, says Markus Rex, an atmospheric scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Potsdam, Germany. In the chilly temperatures, the high-altitude clouds formed, and the ozone-destroying reactions began.

Researchers measure ozone levels by releasing weather balloons from observing stations around the Arctic (including the Polarstern icebreaker, which is frozen in sea ice for a year-long expedition). By late March, these balloons measured a 90% drop in ozone at an altitude of 18 kilometres, which is right in the heart of the ozone layer. Where the balloons would normally measure around 3.5 parts per million of ozone, they recorded only around 0.3 parts per million, says Rex. “That beats any ozone loss we have seen in the past,” he notes.

The Arctic experienced ozone depletion in 1997 and in 20111, but this year’s loss looks on track to surpass those. “We have at least as much loss as in 2011, and there are some indications that it might be more than 2011,” says Gloria Manney, an atmospheric scientist at NorthWest Research Associates in Socorro, New Mexico. She works with a NASA satellite instrument that measures chlorine in the atmosphere, and says there is still quite a bit of chlorine available to deplete ozone in the coming days.

Is it dangerous?

Things would have been much worse this year if nations had not come together in 1987 to pass the Montreal Protocol, the international treaty that phases out the use of ozone-depleting chemicals, says Paul Newman, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The Antarctic ozone hole is now on its way to recovery — last year’s hole was the smallest on record — but it will take decades for the chemicals to completely disappear from the atmosphere.

The Arctic ozone hole isn’t a health threat because the Sun is just starting to rise above the horizon in high latitudes, says Rex. In the coming weeks, there is a small chance the hole might drift to lower latitudes over more populated areas — in which case people might need to apply sunscreen to avoid sunburn. “It wouldn’t be difficult to deal with,” Rex says.

The next few weeks are crucial. With the Sun slowly getting higher, atmospheric temperatures in the region of the ozone hole have already started to increase, says Antje Inness, an atmospheric scientist with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in Reading, UK. Ozone could soon start to recover as the polar vortex breaks apart in the coming weeks.

“Right now, we’re just eagerly watching what happens,” says Ross Salawitch, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Maryland in College Park. “The game is not totally over.”