https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/07/meatpacking-plant-dodge-city/619011/

About beef, about myself, about AmericaBy Michael HoltzJULY/AUGUST 2021 ISSUESHARE

This article was published online on June 14, 2021.https://audm.herokuapp.com/player-embed/?pub=atlantic&articleID=pulling-count-holtz

On the morning of may 25, 2019, a food-safety inspector at a Cargill meatpacking plant in Dodge City, Kansas, came across a disturbing sight. In an area of the plant called the stack, a Hereford steer had, after being shot in the forehead with a bolt gun, regained consciousness. Or maybe he had never lost it. Either way, this wasn’t supposed to happen. The steer was hanging upside down by a steel chain shackled to one of his rear legs. He was showing what is known in the euphemistic language of the American beef industry as “signs of sensibility.” His breathing was “rhythmic.” His eyes were open and moving. And he was trying to right himself, which the animals commonly do by arching their back. The only sign he wasn’t exhibiting was “vocalization.”

MAKE YOUR INBOX MORE INTERESTING

Each weekday evening, get an overview of the day’s biggest news, along with fascinating ideas, images, and people.Email Address (required)Sign Up

THANKS FOR SIGNING UP!

The inspector, who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, told employees in the stack to stop the moving overhead chain to which the cattle were attached and “reknock” the steer. But when one of them pulled the trigger on a handheld bolt gun, it misfired. Someone brought over another gun to finish the job. “The animal was then stunned adequately,” the inspector wrote in a memorandum describing the incident, noting that “the timeframe from observing the apparent egregious action to the final euthanizing stun was approximately 2 to 3 minutes.”

Three days after the incident occurred, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, citing the plant’s history of compliance, put the plant on notice for its “failure to prevent inhumane handling and slaughter of livestock.” FSIS ordered the plant to create an action plan to ensure that such an incident didn’t happen again. On June 4, the agency approved a plan submitted by the plant’s manager and said in a letter to him that it would defer a decision about punishment. The chain could keep moving, and with it the slaughtering of up to 5,800 cows a day.

Eric Schlosser: America’s slaughterhouses aren’t just killing animals

The first time I stepped foot in the stack was late last October, after I had been working at the plant for more than four months. To find it, I arrived early one day and worked my way backwards down the chain. It was surreal to see the slaughter process in reverse, to witness step-by-step what it would take to reassemble a cow: shove its organs back into its body cavities; reattach its head to its neck; pull its hide back over its flesh; draw blood back into its veins.

During my visits to the kill floor, I saw a severed hoof lying inside a metal sink in the skinning room, and puddles of bright-red blood dotting the red-brick floor. One time, a woman in a yellow synthetic-rubber apron was trimming away flesh from skinless, decapitated heads. A USDA inspector working next to her was doing something similar. I asked him what he was cutting. “Lymph nodes,” he said. I found out later that he was performing a routine check for diseases and contamination.

On my last trip to the stack, I tried to be inconspicuous. I stood against the back wall and watched as two men standing on a raised platform cut vertical incisions down the throat of each passing cow. As far as I could tell, all of the animals were unconscious, though a few of them involuntarily kicked their legs. I watched until a supervisor came over and asked what I was doing. I told him I wanted to see what this part of the plant was like. “You need to leave,” he said. “You can’t be here without a face shield.” I apologized and told him that I would get going. I couldn’t have stayed for much longer anyway; my shift was about to start.

Getting a job at the Cargill plant was surprisingly easy. The online application for “general production” was six pages long. It took less than 15 minutes to fill out. At no point was I required to submit a résumé, let alone references. The most substantial part of the application was a 14-question form that asked things like:

“Do you have experience working with knives to cut meat (this does not include working in a grocery store or deli)?”

No.

“How many years have you worked in a beef production plant (example: slaughter or fabrication, not a grocery store or deli)?”

No experience.

“How many years have you worked in a production or plant environment (example: assembly line or manufacturing work)?”

Zero.

Four hours and 20 minutes after hitting “Submit,” I received an email confirmation for a phone interview the next day, May 19, 2020. The interview lasted three minutes. When the woman conducting it asked me for the name of my last employer, I told her that it was the First Church of Christ, Scientist, the publisher of The Christian Science Monitor. I had worked at the Monitor from 2014 to 2018. For the last two of those four years, I was its Beijing correspondent. I had quit to study Chinese and freelance.

“And what did you do there?” the woman asked about my time at the Church.

“Communications,” I said.

The woman asked a couple of follow-up questions about when I quit and why. During the interview, the only question that gave me pause was the final one.

“Do you have any issues or concerns working in our environment?” she asked.

After hesitating for a moment, I replied, “No, I don’t.”

With that, the woman said that I was “eligible for a verbal, conditional job offer.” She told me about the six positions for which the plant was hiring. All were for the second shift, which at the time was running from 3:45 in the afternoon to between 12:30 and 1 o’clock in the morning. Three of the jobs were in harvesting, the side of the plant more commonly known as the kill floor, and three were in fabrication, where the meat is prepared for distribution to stores and restaurants.

RECOMMENDED READING

- The Capitalist Way to Make Americans Stop Eating MeatDEREK THOMPSON

- Slaughterhouse RulesB. R. MYERS

- Amazon Has Transformed the Geography of Wealth and PowerVAUHINI VARA

I quickly decided that I wanted a job in fab. Temperatures on the kill floor can approach 100 degrees in the summer, and, as the woman on the phone explained, “the smell is stronger because of the humidity.” Then there were the jobs themselves, jobs like removing hides and “dropping tongues.” After you remove the tongue, the woman said, “you do have to hang it on a hook.” Her description of fab, on the other hand, made it sound less medieval and more like an industrial-scale butcher shop. A small army of assembly-line workers saw, cut, trim, and package all of the meat from the cows. The temperature on the fab floor ranges from 32 to 36 degrees. But, the woman told me, you work so hard that “you don’t feel the cold once you’re in there.”On the evening before I left for Dodge City, my mom and I went to my sister and brother-in-law’s house for a steak dinner. “It might be the last one you ever have,” my sister said.

We went over the job openings. Chuck cap puller was immediately out because it involved walking and cutting at the same time. The next to go was brisket bone for the simple reason that having to remove something called brisket fingers from in between joints sounded unappealing. That left chuck final trim. That job, as the woman described it, consisted entirely of trimming pieces of chuck “to whatever spec it is that they’re running.” How hard could that be? I thought to myself. I told the woman that I would take it. “Perfect,” she said, and went on to tell me my starting pay ($16.20 an hour) and the conditions of my job offer.

A couple of weeks later, after a background check, a drug screening, and a physical exam, I got a call about my start date: June 8, the following Monday. The drive to Dodge City from Topeka, where I had been living with my mom since mid-March because of the coronavirus pandemic, takes about four hours. I decided that I would leave on Sunday.

On the evening before I left, my mom and I went to my sister and brother-in-law’s house for a steak dinner. “It might be the last one you ever have,” my sister said when she called to invite us over. My brother-in-law grilled two 22-ounce rib eyes for him and me and a 24-ounce sirloin for my mom and sister to split. I helped my sister cook the side dishes: mashed potatoes and green beans sautéed in butter and bacon grease. The quintessential home-cooked meal for a middle-class family in Kansas.

The steak was as good as any I’ve had. It’s hard to describe it without sounding like an Applebee’s commercial: charred crust, juicy and tender meat. I tried to eat slowly so that I could savor every bite. But soon I was caught up in conversation, and I finished eating without thinking about it. In a state where cows outnumber people two to one, where more than 5 billion pounds of beef are produced annually, and where many families—including mine, when my three sisters and I were younger—fill their deep freezer once a year with a side of beef, it’s easy to take a steak dinner for granted.

The cargill plant is on the southeastern outskirts of Dodge City, just down the road from a slightly larger meatpacking plant owned by National Beef. The two facilities sit at opposite ends of what is surely the most noxious two-mile stretch of road in southwestern Kansas. Situated close by is a wastewater-treatment plant and a feedlot. On many days last summer, I found the stench of lactic acid, hydrogen sulfide, manure, and death to be nauseating. The oppressive heat only made it worse.

The High Plains of southwestern Kansas are home to four major meatpacking plants: the two in Dodge City, plus one in Liberal (National Beef) and another near Garden City (Tyson Foods). That Dodge City became home to two meatpacking plants is a fitting coda to the town’s early history. Founded in 1872 along the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, Dodge City was originally an outpost for buffalo hunters. After the herds that once roamed the Great Plains were decimated—to say nothing of what happened to the Native Americans who’d once lived there—the city turned to the cattle trade.

Practically overnight, Dodge City became, in the words of a prominent local businessman, “the greatest cattle market in the world.” This was the era of lawmen like Wyatt Earp and gunfighters like Doc Holliday, of gambling and shoot-outs and barroom brawls. To say that Dodge City is proud of its Wild West heritage would be an understatement, and nowhere is that heritage more celebrated—some might say mythologized—than at the Boot Hill Museum. Located at 500 West Wyatt Earp Boulevard, near Gunsmoke Street and the Gunfighters Wax Museum, the Boot Hill Museum is anchored by a full-scale replica of the once-famous Front Street. Visitors can enjoy a sarsaparilla at the Long Branch Saloon or shop for handmade soap and homemade fudge at the Rath & Co. General Store. Entry to the museum is free for Ford County residents, a deal that I took advantage of many times last summer after I moved into a one-bedroom apartment near the local VFW.

Yet for all its dime-novel-worthy stories, Dodge City’s Wild West era was short-lived. In 1885, under growing pressure from local ranchers, the Kansas legislature banned Texas cattle from the state, bringing an abrupt end to the cattle drives that had fueled the town’s boom years. For the next seven decades, Dodge City remained a quiet farming community. Then, in 1961, a company called Hyplains Dressed Beef opened the first meatpacking plant in town (the same one now operated by National Beef). In 1980, a subsidiary of Cargill opened its plant down the road. The beef industry had returned to Dodge City.

With a combined workforce of more than 12,800 people, the four meatpacking plants are among the largest employers in southwestern Kansas, and all of them rely on immigrants to help staff their production lines. “The packers followed the maxim of ‘Build it and they will come,’ ” Donald Stull, an anthropologist who has studied the meatpacking industry for more than 30 years, told me. “And that’s basically what happened.”https://3246d20dbaf1d2e398ae640359a84593.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

According to Stull, the boom started in the early 1980s with the arrival of refugees from Vietnam and migrants from Mexico and Central America. In more recent years, refugees from Myanmar, Sudan, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have all come to work in the plants. Today, nearly one in three Dodge City residents is foreign-born, and three in five are Latino or Hispanic. When I arrived at the plant on my first day of work, I was greeted by four banners at the entrance, one each in English, Spanish, French, and Somali, warning employees to stay home if they were exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19.

I spent much of my first two days at the plant with six other new hires in a windowless classroom near the kill floor. The room had beige cinder-block walls and fluorescent overhead lighting. On the wall near the door hung two posters, one in English and the other in Somali, that read bringing beef to the people. The HR rep who was with us for most of those two days of orientation made sure we didn’t forget that mission. “Cargill is a worldwide organization,” she said before starting a lengthy PowerPoint presentation. “We pretty much feed the world. That’s why when the coronavirus started, we didn’t shut down. Because you guys want to eat, right?” Everyone nodded.

Read: How the meat industry thinks about non-meat-eaters

By that point, in early June, COVID-19 had forced at least 30 meatpacking plants across the United States to pause operations and, according to the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, had killed at least 74 workers. The Cargill plant reported its first case on April 13. Kansas public-health records reveal that over the course of 2020, more than 600 of the plant’s 2,530 employees contracted COVID-19. At least four died.

In March, the plant started to implement a series of social-distancing measures, including some that had been recommended by the CDC and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. It staggered breaks and installed plexiglass barriers on tables in the cafeteria and thick plastic curtains between workstations on the production line. During the third week of August, metal dividers suddenly appeared in the men’s bathrooms, providing workers with a bit of space (and privacy) at the stainless-steel urinal troughs.

The plant also hired a company called Examinetics to screen employees before each shift. In a white tent at the entrance to the plant, a team of medical personnel—all of whom wore N95 masks, white coveralls, and gloves—checked temperatures and handed out disposable face masks. Thermal cameras were set up inside the plant for additional temperature checks. Face coverings were mandatory. I always wore the disposable masks, but many other employees preferred to wear a blue neck gaiter with a United Food and Commercial Workers International Union logo or a black bandana with the Cargill logo and, for some reason, #extraordinary printed on it.

Catching the coronavirus wasn’t the only health risk at the plant. Meatpacking is notoriously dangerous. According to Human Rights Watch, government statistics show that from 2015 to 2018, a meat or poultry worker lost a body part or was sent to the hospital for in-patient treatment about every other day. On the first day of orientation, one of the other new hires, a Black man from Alabama, described a close call he’d had when he worked in packaging at National Beef’s plant up the road. He rolled up his right sleeve to reveal a four-inch scar on the outside of his elbow. “I almost turned into chocolate milk,” he said.

The HR rep told a similar story about a man whose sleeve got caught in a conveyor belt. “He lost his arm up to here,” she said, pointing halfway up her left biceps. She let this sink in for a few moments, before moving on to the next PowerPoint slide: “That’s a good transition into workplace violence.” She began explaining Cargill’s zero-tolerance policy on guns.

After a 15-minute break, we returned to the classroom for a presentation by a union rep.https://3246d20dbaf1d2e398ae640359a84593.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

“Why are we all here?” he asked.

“To make money,” someone responded.

“To make money!” the union rep repeated.

For the next hour and 15 minutes, money—and how the union helped us make more of it—was our focus. The union rep told us that UFCW’s local chapter had recently negotiated a permanent $2 raise for all hourly employees. He explained that all hourly employees would also earn an additional $6 an hour in “purpose pay,” because of the pandemic, through the end of August. This brought the starting wage up to $24.20. The next day at lunch, the man from Alabama told me how eager he was to work overtime. “Right now I’m trying to work on my credit,” he said. “We’ll be working so much, we won’t even have time to spend all that money.”

On my third day of work at the Cargill plant, the number of coronavirus cases in the U.S. surpassed 2 million. But the plant was beginning to bounce back from the outbreak that it had experienced earlier in the spring. (In early May, the plant’s production output had fallen by about 50 percent, according to a text message sent by Cargill’s director of state-government affairs to Kansas’s secretary of agriculture, which I later obtained through a public-records request.) The superintendent in charge of second shift, a giant man with a bushy white beard and a missing right thumb, sounded pleased. “It’s balls to the wall,” I overheard him say to contractors fixing a broken air conditioner. “Last week we were hitting 4,000 a day. This week we’ll probably be around 4,500.”

From the November 2012 issue: Slaughterhouse rules

In fab, processing all of those cows takes place in a cavernous room filled with steel chains, hard-plastic conveyor belts, industrial-size vacuum sealers, and stacks of cardboard shipping boxes. But first is the cooler, where sides of beef are left to hang for an average of 36 hours after they leave the kill floor. When they are brought out for butchering, the sides are broken down into forequarters and hindquarters and then into smaller, marketable cuts of meat. These are what get vacuum-sealed and loaded into boxes for distribution. In non-pandemic times, an average of 40,000 boxes, each weighing between 10 and 90 pounds, are shipped out from the plant every day. McDonald’s and Taco Bell, Walmart and Kroger—they all buy beef from Cargill. The company has six beef-processing plants across the U.S.; the one in Dodge City is the largest.He showed me how to put on a chain-mail tunic that looked made for a knight, layers of gloves, and a white-cotton frock. He led me to a spot near the middle of a 60-foot-long conveyor belt.

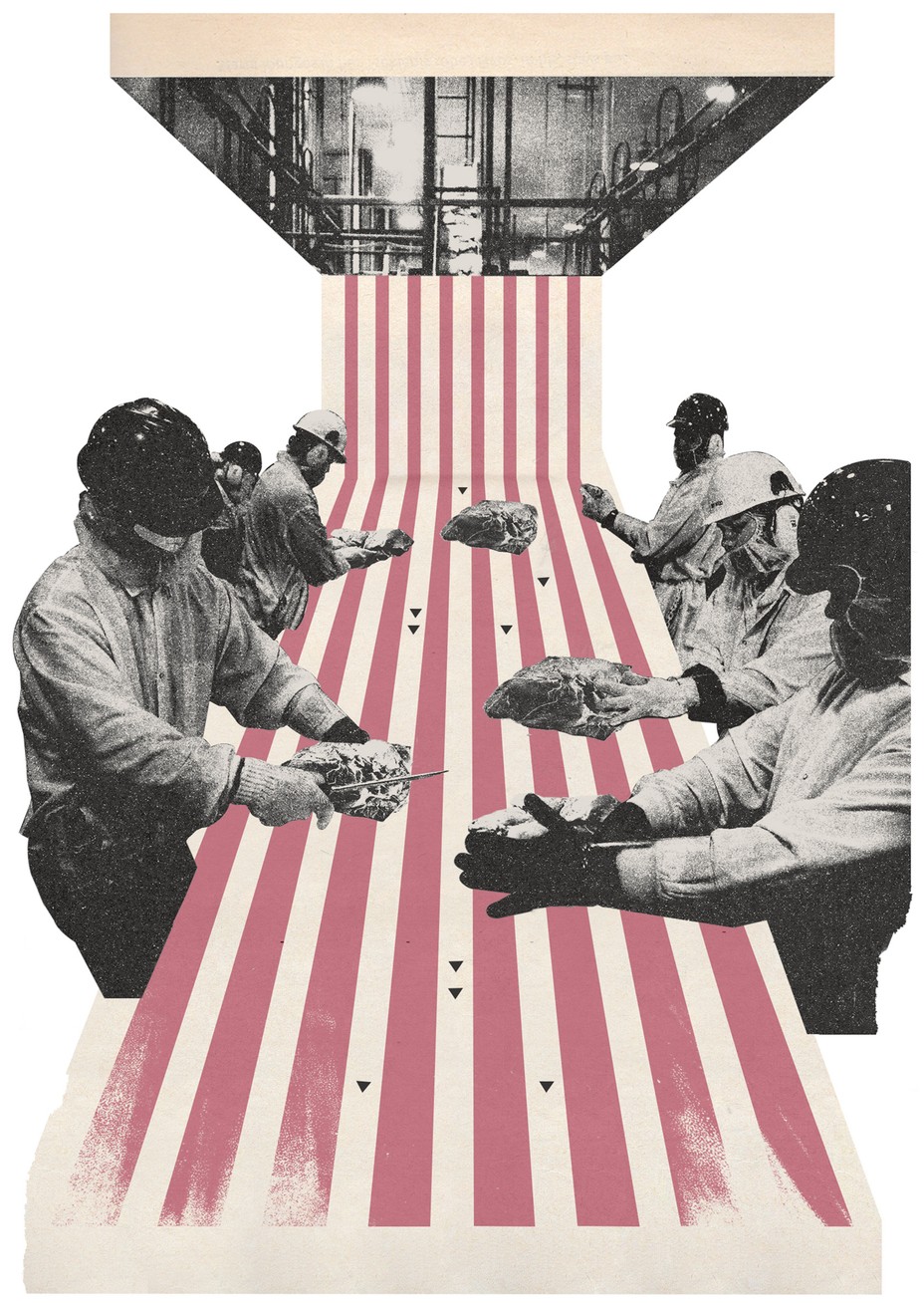

The most important tenet of the meatpacking industry is “The chain never stops.” Companies do everything they can to ensure that their production lines keep moving as fast as possible. Yet delays do occur. Mechanical problems are the most common reason; less common are shutdowns initiated by USDA inspectors because of suspected contamination or “inhumane handling” incidents like the one that occurred two years ago at the Cargill plant. Individual workers help keep the line moving by “pulling count”—industry parlance for doing your share of the work. The surest way to lose the respect of your co-workers is to continually fall behind on count, because doing so invariably means more work for them. The most heated confrontations I witnessed on the line happened when someone was perceived to be slacking off. These fights never escalated into anything more than yelling or the occasional elbow jab. If things got out of hand, a foreman would be called over to mediate.

New hires have a probation period of 45 days in which to prove that they can pull count—to “qualify,” as it’s known at the Cargill plant. Each one is supervised by a trainer for the duration of that time. My trainer was 30, just a few months younger than me, and had smiling eyes and broad shoulders. He was a member of a persecuted ethnic minority from Myanmar, the Karen. His Karen name was Par Taw, but after becoming an American citizen in 2019, he changed his name to Billion. “Maybe I’ll be a billionaire one day,” he told me when I asked him how he had chosen his new name. He laughed, as if embarrassed by sharing this part of his American dream.

Billion was born in 1990 in a small village in eastern Myanmar. Karen rebels were in the middle of a long insurgency against the country’s central government. The conflict raged on into the new millennium—it is one of the longest-running civil wars in the world—and forced tens of thousands of Karen to flee over the border into Thailand. Billion was one of them. When he was 12 years old, he began living in a refugee camp there. He moved to the U.S. when he was 18 years old, first to Houston and then to Garden City, where he went to work at the nearby Tyson plant. In 2011, he landed a job at Cargill, where he has worked ever since. Like many Karen people who arrived before him in Garden City, Billion attends Grace Bible Church. It was there that he met Toe Kwee, whose English name is Dahlia. The two started dating in 2009. In 2016, they had their first son, Shine. They bought a house and got married two years later.

Billion was a patient teacher. He showed me how to put on a chain-mail tunic that looked made for a knight, layers of gloves, and a white-cotton frock. Later, he gave me an orange-handled steel hook and a plastic scabbard filled with three identical knives, each with a black handle and a slightly curved six-inch blade, and led me to an empty spot near the middle of a 60-foot-long conveyor belt. Billion slid a knife from the scabbard and demonstrated how to sharpen it using a counterweight sharpener. Then he got to work, trimming away cartilage and bone fragments and ripping off long, thin ligaments from boulder-size pieces of chuck moving past us on the belt.

Billion worked methodically as I stood behind him and watched. He told me that the key was to cut off as little meat as possible. (As a supervisor succinctly put it: “More meat, more money.”) Billion made the job look effortless. In one swift motion, he flipped over 30-pound slabs of chuck with the flick of his hook and pulled out ligaments from folds in the meat. “Take it slow,” he told me after we switched spots.

More: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/07/meatpacking-plant-dodge-city/619011/