https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20201208-climate-change-can-dairy-farming-become-sustainable

(Image credit: John Quintero/BBC)

By Emily Kasriel8th December 2020Amid polarised debate, Emily Kasriel asks how dairy farmers see the role of their industry in climate change – and finds a mixture of doubt, denial and commitment to change.

“Nothing beats the feeling when you see a cow take its first breath, after battling to get it to breathe. I milk each cow twice a day every single day of the year, so they know I want the best for them,” says Hannah Edwards, standing proudly in the midst of the herd of Holstein cows she’s tended for the last 11 years. They are grazing on her favourite hillside, high up on the farm with a commanding view of peaks and valleys. “I love coming up here. On a clear day, you can see for miles. That’s Wales, Lake Bala is over there, and there you can see Snowdonia.”

With a growing public awareness of the importance of consuming less dairy to meet tough climate change targets, I’ve come to meet Hannah to try and understand how family dairy farmers see climate change. After climbing into her tall green wellies, I drive with her and her Labrador, Marley, to the farm where she works, spread across the border between Wales and Shropshire in the west of England. I want to test whether a communication approach called deep listening could help understand better the attitudes of dairy farmers to the environment and climate change.

Media representations of the climate change narrative have become increasingly polarised, with each side of the discussion represented by partisan outlets as a caricature. But behind these stereotypes are the nuanced stories of how people’s life experiences contribute to their worldview. By having these conversations, perhaps there is common ground that will get us closer to sustainable change.

Where better to start than dairy: in 2015, the industry’s emissions equivalent to more than 1,700 million tonnes of CO2 made up 3.4% of the world’s total of almost 50,000 million tonnes that year. That makes dairy’s contribution close to that from aviation and shipping combined (which are 1.9% and 1.7% respectively).

Dairy farming is Hannah Edwards’ profession and vocation – and the welfare of the herd is always her primary concern (Credit: John Quintero/BBC)

Not long after I arrive at the farm, Hannah, armed with a thick super-sized blue apron and a razor-sharp focus, announces it is time to enter the parlour, where she milks the 140 cows, in a true state of flow. Wrapped in blue gloves, her hands dance in swift parallel moves as they reach diagonally up and then across as she wipes each teat with a disinfecting cloth before attaching it on to the milk sucking equipment. Amid the flurry of muscle action I can feel Hannah’s calm aura of awareness, watching the millilitres on the glass vials track the bubbly white liquid while she reads each cows’ emotional state to pick up on any illness or mood requiring more close attention. “They can’t talk to you, just have to look out for different emotions,” she says. “Their eyes become bulgy when they are scared. It’s really teamwork, cows and farmers working together to produce milk.”

Between 2005 and 2015, the dairy cattle industry’s greenhouse gas emissions increased by 18% as demand for milk grows

The following morning, Hannah and I sit in blistering sunshine on a picnic bench in her family garden alongside her mother Ruth and brother David. “The cows don’t like the heat,” Hannah says. “They won’t sit down as the ground is too hot. Their feet get tender; they get abscesses that cause them to go lame.”

Together, the family reflects on the changing weather and climate patterns they have witnessed. “I remember we used to get frost when we were kids, but we don’t get it anymore,” says David. “We don’t get those nice crisp mornings.” Ruth recalls that when she first came to the farm, the cherry blossom tree would bloom in May. “Now it’s April,” she says. “The climate does seem to be different over the years. We don’t seem to get proper seasons anymore.”

Hannah’s opinions about climate change prove complex over the course of our conversations. “Obviously climate change is happening,” she says. “Greenhouse gases are helped by humans, isn’t it. Part of it is a natural process, like when the Ice Age ended. But it is speeded up, there’s no doubt about that.” And what about the role of farmers? “Farmers have an extra responsibility to take care both of the environment and of emissions,” she says.

But at other moments, Hannah quickly moves the subject away from dairy farming’s contribution. “There are more people, so you need more animals to feed everyone. The bottom line is that we are overpopulated,” she says. “It’s not just this country – there are more people all over the world.”

Greenhouse gas emissions from the dairy industry are rising as demand for milk grows globally (Credit: John Quintero/BBC)

Overall, a quarter of global emissions come from food. The United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) calculated that between 2005 and 2015, the dairy cattle industry’s greenhouse gas emissions increased by 18% as demand for milk grows.

These gases – mainly methane, nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide – are produced at different stages of dairy farming. Methane, the most potent of these greenhouse gases, is first produced as the cow digests its food. Then, as the manure is managed on the farm, methane as well as nitrous oxides are also emitted.

These gases all contribute to global warming. “Carbon dioxide has relatively weak warming effects, but its effects are permanent, lasting hundreds of thousands of years,” says Tara Garnett, who researches greenhouse gas emissions from food at the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford. “A tonne of methane has a far stronger warming effect, but its effect disperses rapidly – in about a decade.”

I sense a conflict between the family’s shared worldview – a deep love and connection with the environment – and to the possibility that dairy farming could be harming the planet

But for Hannah, there is a level of distrust in such facts. “With regard to scientific information, you hope that it’s true,” she says. “But there’s a little bit of me that is quite sceptical. Are they just scaremongering, and forcing us to do things that they want to do?”

As I listen to Hannah and her family, I try to be completely present, using deep listening. I focus on their words, but also try to sense the meaning behind them to better understand their world view. The theory behind deep listening, first explored by psychologist Carl Rogers in the 1950s, is that you convey the attitude that “I respect your thoughts, and even if I don’t agree with them I know that they are valid for you”. When a speaker feels they are being deeply heard they are more likely to convey a richer, more authentic narrative.

I sense a conflict between the family’s shared worldview – a deep love and connection with the environment and the animals they tend – and to the possibility that dairy farming could be harming the planet. “I think [climate change] is a lot to do with cars and aeroplanes,” says Hannah’s brother David. “I don’t think it’s anything to do with farming as we look after the wildlife and the environment… We are not out to damage things.” The experience and family history of being dairy farmers is critical to the family’s identity, so an idea that appears to threaten that heart-felt identity is hard to embrace.

Hannah’s love for the cows, and desire to do everything she can for animal welfare, is the prism through which she sees the world, including climate change

I come to understand that Hannah’s love for the cows, and desire to do everything she can for animal welfare, is the prism through which she sees the world, including climate change. Whenever we talk about a potential measure to reduce carbon footprint or methane emissions, her immediate thoughts are whether the cows will benefit.

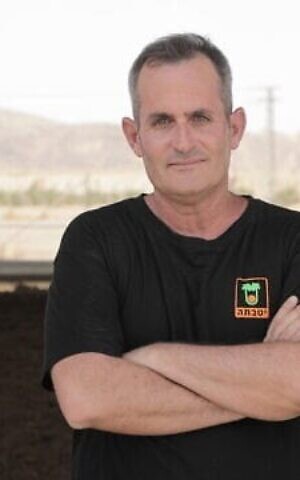

Philip Davies argues that farmers often feel “voiceless and weighted down” (Credit: John Quintero)

After we reach the main farmhouse, her Labrador Marley leads us to Hannah’s boss, Philip Davies, who denies that climate change is happening.

“Climate change is the biggest load of tosh. It’s lies beyond lies,” he says, leaning his arm on the corner of his concrete cowshed, scanning his pregnant cows lying down on the straw inside. “When I was at school not far from here, some of the boys ordered Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. When the books arrived, the headmaster, who used to deliver the post to us boys every morning, would throw them into your porridge. I feel the same about climate change.”

Philip is a tall man who stands erect with piercing blue eyes; he has been a dairy farmer for more than five decades. “I was born a dairy farmer milking a cow when I was six or seven. I remember that first cow, Sylvia, in that farm just down the road, and my father and grandfather before him,” he says. Each precious cow in his herd has a number, but also a name. Mabel, Beryl, Megan, Antoinette, Estelle: names that have echoed through the family herd since the 1950s. Last year, Philip and his three brothers invited 150 neighbours, friends and those they do business with to a marquee to share a meal of meat pies, and bread and butter pudding, listening to stories of their grandparents to celebrate the century their family has been milking cows.

As I hear more from Philip about his experience of farming, a pattern begins to emerge of periodic catastrophes that have shaped his history. “I remember foot-and-mouth disease in the late 1960s,” he recalls. “I was at school, it was the start of October, and I went to play sports. I could see fires all the way from Manchester with the cows burning.” Philip then tells me about the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) outbreak – better known as “mad cow disease” – when he lost 30 cows overall. He vividly remembers the day the vet condemned three of his cows in one day, putting them down in his yard. “It was a tragedy,” he says. After BSE, there has come a drive to reduce tuberculosis levels in cattle. “It changed from something we lived with to a massive issue,” he says, his voice filled with frustration and sadness.

Farmers are the most optimistic people I know, but scratch under the surface, we are carrying disappointment and anger – Philip Davies

Philip feels that cattle farmers have a raw deal. “It’s toughest on the youngsters like Hannah.” Philip is keenly aware of how hard Hannah works, not only with the cows but also in masterminding all the paperwork. He says he would love her to have a more secure future in dairy farming, in which the price of milk would reflect the extraordinary hours and hard toil she pours into the job.

The deep listening technique can be an insightful way to learn more about someone’s views, even if you disagree with them (Credit: John Quintero/BBC)

On the second day of my trip to the farm, I awake early to walk in the surrounding fields, to try and make sense of Philip’s outlook – one that rejects humanity’s huge contribution to the warming of the planet as well as the significant emissions caused by dairy farming. The dry yellow corn is thigh high, and the morning mist hangs heavy, prescient of another intensely hot day. The wide landscape gives me a sense of perspective, and an insight into Philip’s “deep story”. I sense the pride he feels about the intensity of his lifetime of labour alongside a disappointment about the lack of respect that such toil is given and a fear when he looks to the future.

Philip is uncertain whether he can sell his cows and retire in the coming years without his farm being clean of tuberculosis. He feels powerless that he’s forced to send cows who test positive for tuberculosis to be slaughtered, when he has no faith in the validity of the test, though research shows that the rate of false positives for a skin test is around one in 5,000. While on the surface tuberculosis tests have nothing to do with the evidence for climate change, I sense a wider distrust of scientific authority connecting the two.

“We feel voiceless and weighted down,” Philip says. “Farmers are the most optimistic people I know, but scratch under the surface, we are carrying disappointment and anger. We’ve been silenced by everyone pointing the fingers at us. ‘You naughty people, you are ruining the planet.'”

Two days after this conversation, Philip calls me, wanting to tell me about the very first time he felt wrongly accused as a dairy farmer. He remembers sitting round the table with his family listening to the radio in the 1970s and hearing a story about how drinking milk was causing cancer, a story later dismissed as untrue. He conveys the depth of traumatic experiences he has endured and the multiple occasions on which he feels dairy farming, his own calling, had been unjustly targeted. In his eyes, climate change is yet another example of the “faceless men in dark corridors” looking for a scapegoat and seizing on the usual suspect – farmers.

Now that Philip has had time to reflect, I want to know how he found our conversation.”It was refreshingly honest,” he replies. “I just felt that you were actually listening. You hadn’t got an agenda and came with a clean piece of paper. That was very noticeable.”

Increasingly extreme weather has been noticeable in the Shropshire countryside and has been making the jobs of dairy farmers harder (John Quintero/BBC)

On the final evening of my visit, Philip, Hannah and I eat together in the garden of the local 17th-Century pub, a focus for the community. Philip has brought reams of the farm’s paperwork, proudly pointing to a figure of 7,520 litres, the average quantity of milk produced per cow over the year. It’s a high number but less than what cows on intensive farms are producing, according to the University of Oxford’s Garnett. “We don’t push the cows – forcing them to produce more milk,” says Hannah. “We don’t think it’s good for them.”

Hannah feels that the small-scale dairy herds in her family and among those closest to her aren’t really the big greenhouse gas contributors. “When people complain about dairy farmers, they are probably thinking about the way people farm in the US, much more intensively with little regard for the land.”

How does the science stack up on small scale versus intensive dairy farming when it comes to climate change? I turn to Taro Takahashi, a sustainable livestock systems researcher at the Cabot Institute for the Environment, University of Bristol.

“While less intensive farming is generally better for animal welfare and in many cases also beneficial to local ecosystems, its carbon footprint is almost always greater per litre of milk compared to more intensive farming,” says Takahashi. “This is because much of the methane and nitrous oxide emissions attributable to a cow would happen regardless of how much milk they produce. If the cow produces more milk, the emissions per litre declines.” At the same time, Taro points me to a recent study which suggests the intensive approach is only more beneficial if it is linked to more wilderness being spared the plough.

Despite Philip’s denying climate change, the dedication to the welfare of the cows that he shares with Hannah does in fact align with one evidence-based recommendation for lowering greenhouse gas emissions from the dairy industry. Improving animal health monitoring and preventing illness is one of the 15 top measures identified by the management consultancy McKinsey to reduce farming emissions. With fewer calves dying young and less sickness, less methane and other emissions are released per litre of milk.

Hannah, Philip and Ben may have differing views on climate change, but they have a sense of duty to the environment in common (Credit: John Quintero/BBC)

Lorraine Whitmarsh, director of the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations at the University of Bath, studies the challenges of communicating the reality of climate change. It gets tougher when climate change messages are threatening to our values, lifestyles or political ideology. She tells me we are motivated to agree only with the parts of the climate change narrative that align with our livelihoods or core beliefs, denying our responsibilities if the implications of accepting them would be challenging for us. This is a psychological behaviour termed “motivated reasoning”, and it keeps us on the lookout for facts or opinions that reinforce our values and beliefs. I recall Hannah, who is strongly rooted in her community, telling me proudly about the positive impact on the environment of buying more locally produced food.

And, working alongside motivated reasoning, there is another psychological behaviour that acts to help us ignore or dismiss information that threatens our values and beliefs: “confirmation bias”. So, for example, Philip ignores the evidence for significant global warming from human activity, but is finely tuned to stories revealing mistakes by climate scientists.

How can we encourage a more constructive discussion with people who either deny anthropogenic climate change or their own contributions to it? Whitmarsh points to the importance of understanding someone’s values and identity. Her research in the UK demonstrates the effectiveness of narratives emphasising saving energy and reducing waste to reach people less concerned and more sceptical about climate change. Meanwhile, research led by Carla Jeffries of the University of Queensland, Australia, suggests that framing climate change action as showing consideration for others, or improving economic or technological development, can have more impact with climate deniers than focusing on avoiding climate risk. Whitmarsh also tells me we are also more likely to trust climate change messaging if it comes from someone within our own community.

For Ben Davies, adapting the dairy industry to reduce its emissions is a top priority (Credit: John Quintero/BBC)

Back on the farm, Hannah receives a call from Philip, who wants to introduce me to his youngest brother, Peter, who owns 220 cows, the other half of the original family herd. Given that Philip is convinced the Earth is not heating up and he’s keen that I meet his brother, I anticipate that I’ll hear a similar perspective. But that’s not quite the case.

There’s a definite change in the climate – and it’s making our job a lot harder – Peter Davies

Hannah and I sit at a table in Peter’s lovingly tended garden at the edge of his fields, alongside his son Ben, 29, who works full-time with him on the farm.

“There’s a definite change in the climate – and it’s making our job a lot harder,” says Peter. His son Ben agrees that the weather is getting hotter and more extreme. “Being in the country, outdoors all day, you notice things more,” says Ben. “You see the change in weather patterns and with the rivers – you can see flooding and damage and what’s it doing.”

Father and son lead us round the back of the garden to the huge steel and concrete shed they have built to house the cows in separate cubicles, alongside a steel fibreglass tower that stores manure. The cows spend all winter in the shed on rubber mats, and the manure flows down with gravity into a channel. The manure then gets pumped into the tower, where it is ready to be injected into the soil as fertiliser in spring and late summer. Using this stored manure means there is less need for synthetic fertilisers, reducing costs as well as the carbon footprint of fertilising the fields. Injecting manure in this way also reduces emissions of ammonia, which can damage ecosystems and break down into nitrous oxides (a greenhouse gas).

Before moving to this system, the cows were kept on hay and mucked out every three weeks. “This new cubicle system, it’s a lot less work, with far less waste,” says Ben.

I think there is a strong need for more action, we are going too slowly – Ben Davies

I have a sense from Peter and Ben that rather than feeling like victims of the changing climate, their understanding of the bigger picture has given them a sense of agency, a desire to adapt and a willingness to take risks to do so. Peter, spurred on by Ben, has recently made these significant investments, amounting to some £400,000 ($530,000), to make their farm more efficient and reduce its climate and environmental impact. “Ben is the driving force,” Peter says. “It’s people between 25-35 years old, in their prime. You need to let them get on with it when they are at their most persuasive.”

I’m curious about how Ben came to have these insights into climate change and learn about the adaptations needed to reduce the farm’s methane and carbon footprint. “I learned on the internet. I’m self-taught, and then I taught it to others in the pub,” Ben replies.

More than just reducing his own footprint, Ben is in favour of larger policy changes, such as farms needing to meet environmental targets before they are allowed to expand. “I think there is a strong need for more action, we are going too slowly,” he says. Peter agrees: “We’ve got to change.”

Ben Davies and his father Peter have invested substantial sums in emissions-reducing technologies on their farm (Credit: John Quintero/BBC)

Among this small group of Shropshire farmers, the views on dairy and climate cover much of the spectrum of debate. So how do they make sense of each others’ differing views on climate?

“My uncle Philip is one of the old generation,” Ben says. “He will be retiring soon. I don’t think you can win over people. It’s more about our generation making an impact.”

Given his knowledge and commitment to reducing climate change, how does Ben respond to critics who argue that we may have to stop eating meat and dairy entirely to make a significant dent in emissions? He pauses. “I think it’s a small minority, who are trying to ruin our future and a business that our family has tried to develop over 100 years. Come to my farm and have a look,” he says. “I can show you what we are doing to reduce our emissions footprint, and all the infrastructure we are investing so heavily in.”

When it’s time to leave, I ask Hannah if hearing from Peter and Ben has changed her perspective. She harbours dreams of renting her own dairy farm with a small herd and setting up an ice cream business. If she is able to realise her ambitions, would she take steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

“I suppose you would have to see the figures, but if we could catch the rainwater to wash the milking parlours and got wind turbines and solar panels to supply electricity, it wouldn’t affect us farmers,” she says. “If there was a way to do our bit and our country did start making steps to improve our emissions, maybe other countries would follow.” But her doubts seem to catch up with her quickly. “But maybe Philip is right? We don’t know who is right and wrong – we don’t know the facts.”

Where Hannah remains unsure about dairy farming’s climate impact, there is another certainty that she will always come back to: her guiding principle.

“Cows are the most important thing. That’s the way I look at it. As long as the cows are happy, we are happy.”

—

This article is published in partnership with

This article is published in partnership with