Before I was an animal rights activist, I was a budding human rights activist. While in law school, I helped victims of domestic violence obtain personal protection orders. I studied human rights and refugee law, participated in an asylum clinic, spent all my summer legal internships working with refugee organizations and focused primarily on helping women who were victims of gender-based persecution and violence such as honor crimes, forced genital mutilation, sex-trafficking, and rape.

My first client let me touch the shrapnel that was embedded under the skin in her knee after the Taliban had bombed her village in Afghanistan and killed most of her family. I also represented men when they were in need, like the gentle Congolese man who had been tortured, and had the marks on his body to prove it, because of dubious ties to the wrong political party.

Refugees and victims of gender based violence are an incredibly vulnerable and deserving group of humans. Many of them have no family, no country. Many live their lives in fear. Without the help of international aid groups and non-governmental organizations, they are at constant risk of exploitation, abuse, persecution, homelessness, and death. And yet, I have chosen to dedicate myself and my life to the animals.

I’m sure every animal activist has been challenged on this point: “How can you waste your time on animals when there are so many humans suffering?!” “Why don’t you start with the humans, and when all of our problems are fixed, then you can help animals?”

Of course this is the dominant mentality, based on a presumed superiority of humans, so much so that the slightest harm to a human is often seen to outweigh a tremendous harm to an animal. Given that the capacity to suffer is in no way limited to human beings, this bias in favor of humans is simple prejudice, favoring those we perceive as similar over those we perceive as different and therefore inferior, the hallmark of all discrimination and oppression.

For years I felt paralyzed as I looked out at the world with all of its suffering.

I desperately wanted to help but didn’t know how I could possibly choose between helping the people in third world countries living in extreme poverty, and the millions of children under the age of five dying every year from malnutrition, or the victims of ethnic and religious wars that so brutally claim the lives of innocents at any given time in modern history, genocides like that in Rwanda, Bosnia, Darfur, atrocities taking place right now in Libya, Syria and Yemen. Millions of people, mostly women and girls, are bought and sold into the world of sex trafficking every year to endure unspeakable crimes. And then there are the animals being used for painful and often cruel experimentation in laboratories, the fur-bearing animals like the playful foxes who are killed by anal electrocution so as not to damage their fur or the Chinese raccoon dogs who are routinely skinned alive in order to make knock off UGG boots or for the cheap fur trim on our winter coats. [1]

But the number of all of these animals combined is a drop in the bucket compared to the 55 billion farmed animals we kill every year for food. Fifty five billion animals. The entire global human population is about 7 billion, and we kill 55 billion animals every year for food. Each and every one of those fifty five billion was an individual with the capacity to have bonded with family and friends and to have led a joyful life like the rescued pigs seen in this video but who instead led a life of intense misery and often sadistic exploitation before enduring the terror and pain of slaughter.

All of these human and nonhuman beings suffer terribly. All of them are worthy of our compassion. I have always wanted to help them all. I still do. But the reason I choose to dedicate the majority of my time to advocating for nonhuman animals rather than all of those deserving humans is that we as a society all basically agree on human rights.

When I say we as a society, I do not mean the moral outliers of the international community like members of ISIS, or those in our own society like rapists or serial killers, but those who represent the dominant ethic in the world community, the law abiding members of our society and the international community. And according to that dominant ethic, it is wrong to abuse woman and children. It is wrong to murder innocent men. When we see humans who are starving or being exploited, raped, kidnapped, murdered or tortured, we believe it is wrong. Most governmental bodies around the world, non-government organizations (NGOs), and individuals agree that it is wrong to cause intense physical or emotional pain and suffering to human beings. We criminalize such harm, and we punish those who commit these crimes.

The same cannot be said of animals, especially not farmed animals, whose abuse is accepted by the same moral community that rejects the abuse of humans.

Even those of us who shower our dogs and cats with affection do so while sitting down to feast on a meal comprised of the body parts of equally sentient beings whose entire lives were spent in suffering. As a society, we still do not see what we’re doing to animals as wrong. While all animals in our society are still legally considered property, at least abusing dogs and cats is now a felony in all fifty states. However, what is felony cruelty if done to a dog or cat is perfectly legal if done to an animal we have designated as a food animal. [2]

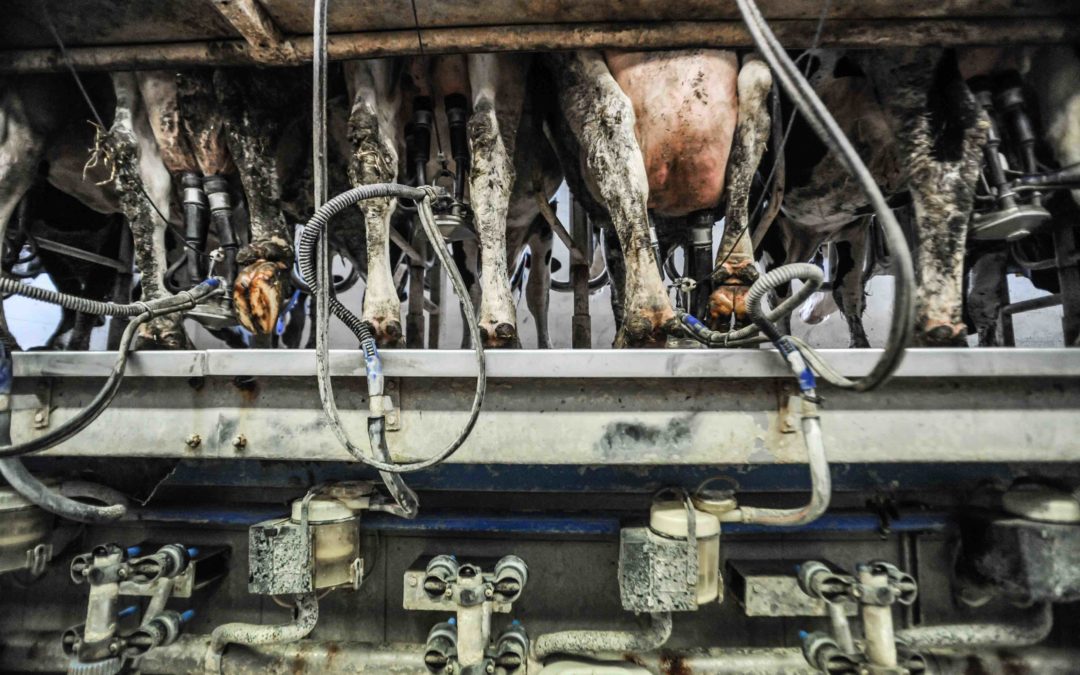

We not only kill 10 billion land animals in the US every year for food, (55 billion globally) it would not be an exaggeration to say that we torture them for the duration of their short lives before we kill them. We confine them in tiny cages that drive them literally insane. [3] We take babies away from their mothers and murder them by the millions (e.g., we kill 260 million baby chicks every year because they are a “by-product” of the egg industry). [4] Dairy cows are impregnated on what the industry calls a “rape rack” in order to ensure the cow will continue to lactate and provide milk that will be denied to her baby, who will be taken away at birth. If that baby is female, she will become a dairy cow and like her mother, she too will be forcibly impregnated, and then after giving birth to four or five babies and milked so much the odds are she will suffer from a painful udder infection called mastitis, she will be slaughtered at a fraction of her natural lifespan when her body becomes too depleted to continue producing milk at the volume modern agribusiness demands. If the baby the dairy cow births is a male, he will either be killed on the spot, or turned into veal (i.e. confined all alone in a dark pen and fed an iron deficient diet to make him anemic because consumers prefer the taste and color of meat that comes from anemic babies). [5]

Nonhuman animals are conscious, intelligent, emotional beings.

If we have ever lived with a dog or cat, we probably know this from experience. If we need proof, we can ask the scientific community. In 2012, a prominent international group of cognitive neuroscientists, neuropharmacologists, neurophysiologists, neuroanatomists and computational and neuroscientists gathered at The University of Cambridge and declared that nonhuman animals are conscious – meaning they can think, feel, perceive, and respond to the world in much the same way as humans. [6]

It is hard to measure pain. Usually with humans we just ask them how much pain they feel and they tell us. But when they can’t tell us, we look for external signs of pain such as trying to get away from the source of pain, vocalizing (yelling, crying), grimacing or shaking to name a few. Nonhuman animals demonstrate all of these same signs. If we can bear not to look away, it is plain to see that the egg laying hens crammed into battery cages, or the sows confined to gestation creates so small that can’t turn around, or the dairy cows being dragged to slaughter because they are too lame to walk all suffer tremendously.

Just a few hundred years ago, Rene Descartes, the father of western philosophy, strapped living dogs to tables and cut them open without anesthesia believing that their howls were like the sounds made by machines, no more indicative of pain than was the screech made by the machine’s metal parts. Hard to imagine, that. And yet today even on so called humane farms, we routinely subject cows, pigs, chickens, turkeys and other farmed animals to mutilation without anesthesia. [7] If we think what Descartes did was wrong, how can we possibly condone what we do to farmed animals every single day? There is no reason to believe that a dog feels more pain than a pig or for that matter that a human feels more pain that a dog. Some, like evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, think non humans may even feel pain more acutely than humans do. [8] In fact we are so certain that nonhuman animals do feel pain like humans do that we subject animals like mice to pain tests in labs in order to better understand human pain. [9]

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that at least a million chickens and turkeys are boiled alive every year because the production line is so fast that their throats haven’t been slit by the time they get to the tanks of scalding water into which they are dropped, only to be boiled alive. [10] More than 1 million pigs die in transport every year before they even get to the slaughterhouse. [11] They are packed in so tightly they cannot move, and can barely breathe. They die of suffocation, overheating, being trampled.

I became an animal rights advocate not because I don’t care about humanity, but because so few people care about the nonhuman animals.

The suffering of animals we use for experimentation, for fur, for our food is shocking to the conscience. Watch one undercover slaughterhouse video and we might think the vile cruelty we see is an anomaly. Watch hundreds and hundreds of these videos and we begin to realize that the disdain with which the workers treat the animals, kicking chickens like footballs, [12] kicking and stomping turkeys destined for Thanksgiving dinner, [13] slamming piglets onto the concrete floor and leaving them to die, [14] is not anomalous but is the norm.

The degree and scale of the suffering involved in animal agriculture in particular is beyond anything humanity has ever endured.

Polish-born Jewish-American author Isaac Bashevis Singer famously said “In relation to [the animals], all people are Nazis; for the animals it is an eternal Treblinka.” This refers of course to the Nazi concentration camp where close to a million Jews were exterminated in gas chambers. The first time I ever heard the comparison made between factory farming and the Holocaust was by someone who lost most of his family in the Holocaust and who himself is a survivor of it. Alex Hershaft is an animal rights pioneer who has said that his experience in the Holocaust not only contributed to his becoming a vegan and an animal rights activist, it is the cause of it. During a recent trip to Israel, he had this to say in an interview:

“The Jewish Holocaust is a unique event in human history; and the best way to honor the Holocaust is to learn from it and to fight all forms of oppression. We may have been victorious in World War II, but the struggle against oppression and injustice is far from over. For me, the Holocaust isn’t a tool in the struggle, but an experience that shaped my personality and my values, made me who I am today, and drove me to fight all forms of oppression, including the oppression of the weakest creatures, the animals.” [15]

In his latest book, “The Most Good You Can Do,” one of the modern world’s pre-eminent philosophers of ethics, Peter Singer, argues that if we are interested in doing the most good we can do in the world, that is, in reducing the most suffering, there are three main areas that demand our attention. These are saving the environment, ending extreme poverty, and helping the nonhumans animals, especially farmed animals.

In addition to its importance for the nonhumans, vegan advocacy goes beyond helping nonhuman animals. Vegan advocacy seeks to raise consciousness and awareness about the ways in which we treat other beings. The animal rights movement does not just advocate for a select group of beings, it advocates for principles truly universal in their scope.

Animal rights advocates don’t just advocate for the rights of chimps or cows or fish. They advocate for a more compassionate world for all beings.

They bring awareness to structures of power that are oppressive and based on exploitation, that harm nonhuman animals, humans, and the environment. Veganism is rooted in the concept of ahimsa, a Sanskrit word meaning non-harm to all sentient beings as well as the living environment. It is a movement that above all values the reduction of suffering, and calls on us all to bring more awareness into the ways in which we relate with all beings, the nonhumans as well as humans. Fundamentally, vegans advocate for the values that all social justice movements uphold. They focus on the nonhumans, but what they are really advocating for is a society in which no sentient being is used as a means to another’s end. They are fighting for the elimination of all forms of prejudice and oppression. They work to build a world where no sentient being is discriminated against based on morally irrelevant qualities, where all beings are valued and respected, where none are enslaved or tortured, where all beings are allowed the freedom to thrive and pursue their own innate potential for happiness and joy. As long as our society is built on a foundation of brutality, oppression and exploitation of billions of sentient beings, how can we ever hope to have true justice or compassion within human society?

Being an animal rights activists is not about limiting our compassion to nonhumans, it’s about extending our circle of compassion to include all beings who can suffer.

In the world we live, there is no comparison to the enormity of the suffering endured by the nonhuman animals, especially those enslaved by the meat, dairy, and egg industries. I am an animal advocate because the screams of billions of animals remain unheard. I am an animal advocate because no being should suffer, and the suffering of nonhuman animals is so intense, so constant, so massive, and so widespread. I am an animal advocate because humanity is still in denial that it is our own daily choices that are responsible for the immense suffering of a truly unfathomable number of conscious, emotional, sentient beings. I am an animal advocate quite simply because it is the animals who need me the most.

[11] “Research Looks at Transport Losses,” Feedstuffs Apr. 17 2006.

Top photo: Pigs living out their lives at the wonderful Poplar Spring Animal Sanctuary in Poolsville, MD.