This issue is why I started my website: animalsinthewild.com

——————————————————–

The dark side of those wondrous wildlife photographs.By Ted WilliamsMarch-April 2010

Popular Stories

Reverse the Rollback of the MBTA

Speak out to reinstate critical bird protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.Take Action

Audubon has sent me to lots of wild places over the past 31 years, but I’d seen only one wolf and three cougars (a litter) until December 8, 2009. On that day, before noon in the Glacier National Park ecosystem of northwestern Montana, I encountered not just one wolf but two and not just one cougar but two! What were the chances of that?

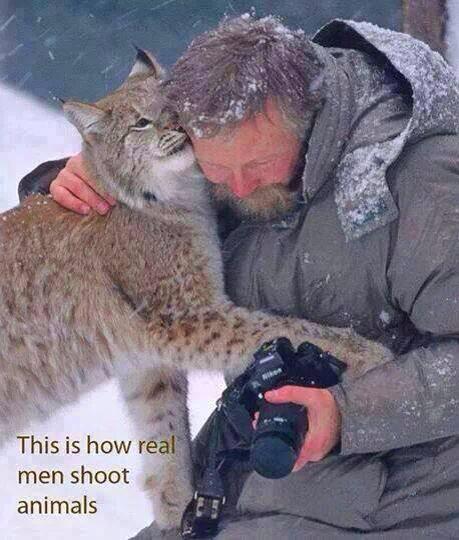

Well, they were 100 percent, because I’d rented the animals for a photo shoot. As a photographer I’ve done my best work with Kodak disposable cameras, so advertising photographer Andrew Geiger would do the shooting under my direction. By his own admission Geiger lacks the patience to be a wildlife photographer, but that was okay because our subjects weren’t wildlife. “Captive wildlife” is an oxymoron.

The “models,” as the industry calls them, were beautiful and healthy, though. At 8:30 a.m.—after a long sleep and a hot breakfast in the Triple D guest house equipped with kitchen, refrigerator, TV, living room, and gas-fueled fireplace—I was ready for my three hours in the field. Behind the Triple D office Geiger and I met our first model—Jewel, a little two-year-old cougar who paced and mewed behind the bars in the back of the truck. By the time trainer Logan Saich had driven us to the scenic set leased by Triple D, the day had warmed from minus 24 degrees Fahrenheit to minus 16.

Saich led Jewel to high ground, where she posed like Kate Moss against magnificent snow-clad peaks. Surprised by the snow and ice, she raised and shook each paw the way my cat Moop had done the time she stepped in turpentine. Jewel was coming into heat, so she chased her melon-sized plastic ball only halfheartedly and swatted none too ferociously at the deer-hair toy Saich dangled in front of her. Still, this was the high point in her dreary day. On our way down Saich had to carry her, and she grabbed the last fence post with both front paws. The strong bond between trainer and model was obvious. “Good girl, good girl,” Saich murmured when she let go. She purred when he scratched her behind the ears.

Back at the game farm, Attilli, the three-year-old cougar, performed better. He was obsessed with his ball, bounding over logs in pursuit and looking very fierce. Saich had difficulty prying it from his grasp. Once Saich rubbed leaves off Attilli’s nose to make him more photogenic. All too soon for Attilli he was back in his cage. Then came Big John, the black wolf, who saluted everything in sight because he was the alpha male. Behind us 17 other wolves started a baleful chorus. Big John placed his forepaws on a rock, as he’d been trained, and snapped up the beef-heart treat Saich threw to him. “Good boy!” exclaimed Saich, and Big John whirled around, put his paws back on the rock, and fielded another treat. Even more enthused with the romp and treats was Lakota, the cream-colored wolf. He dashed around the enclosure, looking wild and voracious, then rolled on his back for a belly rub.

“You couldn’t have gotten those shots in the wild,” Triple D co-owner Jay Deist told me, and he was right. In 1972 he, his brother, and his father opened Triple D, but not for photographers. They were “going to save the world” by capturing and breeding vanishing wildlife. It didn’t work out. But soon photographers began paying for sessions with the animals. Deist describes the early clientele as “very secretive, because they didn’t want anyone to know the source.” Concurrently, these amazing “wildlife photos” started showing up in magazines, calendars, and posters—close-up action shots with every whisker in perfect focus. Similar game farms sprang up around the country, though no one knows how many there are.

Deist, a former law-enforcement officer for the U.S. Forest Service and the son of a Montana game warden, is generally regarded as the best game-farm operator in the nation. When it comes to animal care, honest business practices, and obeying state and federal regulations, he does everything right.

But are game farms right? “If you are interested in photographing a snow leopard in winter conditions, this is the time of year,” reads a Triple D ad distributed by the North American Nature Photography Association (NANPA) as an alleged service to its members. Images of Triple D’s snow leopards are proliferating like Internet pop-ups. In 2008 one even received first place in the “nature” category of National Geographic’s International Photography Contest. Animals like snow leopards are in desperate trouble, but why should people believe this when they see sleek, healthy snow leopards every time they walk into a bookstore or open a “wildlife” calendar. A major threat to eastern forest ecosystems is the irruption of white-tailed deer. But the public shouts down increased hunting of does—the only means of control—partly because it gets saturated with photos of game-farm deer on which there is never a tick, sore, clouded eye, or protruding rib. “I understand that people need to make a living, and it’s easier to rent an animal for an afternoon,” says National Geographic’s photo editor for natural history, Kathy Moran. “They claim these animals are ‘wildlife ambassadors.’ No. An injured animal used for education—that’s a wildlife ambassador. An animal kept solely for profit is an exploited animal. The wild isn’t pretty. I’d rather see it real than all gussied up. When I see a poster of a big, beautiful air-blown lion with a mane that looks better than my hair galloping toward me, I feel cheated.”

Of course, a photo of a tame animal isn’t a lie if it is clearly identified as captive. Deist advocates “full disclosure.” But what is full disclosure? The National Wildlife Federation’sRanger Rick magazine deserves much credit for being the first publication in the nation to label captive shots. But is the symbol for captive—a “P” with a circle around it—in Ranger Rick and the federation’s two other kids’ magazines, Your Big Backyard and Wild Animal Baby, “full disclosure”? Only for the child who notices it, then flips to the table of contents and consults the note. Is full disclosure a caption that says “controlled conditions”? What are controlled conditions? Is full disclosure a photo credit that says “captive”? In a few situations, where format precludes captions, maybe that’s as close as possible. But credits often go unread.

Even photos taken in the wild can lie if they’re “photoshopped.” In Audubon’s photo contest (“The Big Picture,” January-February 2010), the judges had to disqualify a shot in which vegetation had been digitally transplanted. Last November the National Wildlife Refuge Association disqualified a semifinalist from its photo contest for digitally staging an exeunt for undramatic bird extras, adding a moon, and opening the eye of an oystercatcher. “Ethically challenged,” is how Evan Hirsche, the association’s president, describes the photographer. But such deceptions are standard in the publishing industry.

Then there’s the humane issue. For many game-farm animals life is hard and brief. According to documents I obtained from Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Animals of Montana—a game farm near Bozeman at least as popular as Triple D—euthanized eight wolves in 2007 because they were “dangerous.” In other words, their behavior was too wolflike. The spring 2009 issue of Currents, NANPA’s newsletter, quotes a photographer who requested anonymity as saying this about her first and last visit to Animals of Montana: “The owner took out a mountain lion, but the lion didn’t want to come. There was kicking and dragging and yelling.”

I definitely needed to see Animals of Montana’s famous grizzlies, which “love to perform [and] will amaze you by running towards the camera, standing on command, snarling viciously or posing cute.” But when I tried to book a session, Tracy Krueger, companion and business partner of owner Troy Hyde, said she was “excited” to report that the operation was “switching hands.” This, I learned from court documents, was because Hyde had filed false information with the feds and had been convicted of illegal wildlife trafficking in violation of the Endangered Species Act and the Lacey Act. On April 27, 2008, shortly after the USDA moved to terminate Hyde’s exhibitor’s license, Krueger applied for a license. The USDA saw it as a ruse—i.e., “an attempt to circumvent the impending termination”—and rejected the application. On June 6, 2008, Hyde’s lawyer, Bret Hicken, applied for a license. The USDA saw that as another ruse, noting that to obtain a license any new operator would have to purchase animals and property. Apparently that has happened, because on November 9, 2009, Hicken signed a consent agreement with the agency to reopen the game farm as Animal Industries, but this wouldn’t happen in time for my article. According to the Associated Press, animals from Hyde’s game farm “have appeared in a number of films, including some by National Geographic, Turner Original Productions, and the BBC.”

While in Montana I tried to visit Wild Eyes Photo Adventures in Columbia Falls, which had illegally trafficked in wildlife in violation of the Lacey Act and “willfully” violated the Animal Welfare Act. I had reliable information that Wild Eyes kept river otters in small cages, but I was unable to confirm this because Wild Eyes is out of business. I couldn’t visit the DeYoung Family Zoo, a game farm in Wallace, Michigan, still in business despite its owner, Harold DeYoung, being busted for Lacey Act and Endangered Species Act violations. “What do they do with all these babies?” inquires genuine wildlife photographer Don Jones about the industry’s “new baby” promos, which appear like crabgrass every spring. No one knows, but in 2004 a game farm in Sandstone, Minnesota—still in business as Minnesota Wildlife Connection—sold its tame black bear Cubby for $4,650 to country music star Troy Gentry, who then illegally “hunted” and killed him in his pen with a bow and arrow.

‘‘Nature fakery has been going on in photography since the days of glass plates,” declares genuine wildlife photographer Les Line, Audubon’s editor from 1966 to 1991. “The earliest issues of Audubon [circa 1903] tried to pass off photos of stuffed birds as live ones. That’s minor compared to what’s been happening since.”

Especially impressive were the innovations of Disney in the 1950s and ’60s. In apologizing for the early films, which he helped produce, Roy Disney accurately noted that they promoted “awareness” of nature—at least nature the way he and his colleagues depicted it. Since then the Disney Company has progressed light years in quality and honesty with films like Earth (2009), but the early work provides important historical perspective and explains some of our society’s lingering misperceptions about nature. For example, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s 2008 documentary Cruel Camera takes a behind-the-scenes look at White Wilderness(1958), revealing that the polar bear cub bouncing spectacularly down a snowy, rock-studded mountain was thrown over the side. Lemmings don’t commit mass suicide any more than hummingbirds hitch rides on southbound geese. But Disney paid kids in Churchill, Manitoba, to catch lemmings, then transported them to non-habitat in Alberta where a turntable flung them off a cliff and into “the sea” by the dozens. White Wilderness, which won an Oscar, is still sold on DVD as a “true-life adventure.”

Inspired by Disney were Marlin Perkins, host of Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom (premiering in 1963), and Marty Stouffer, host of the Public Broadcasting Service’s Wild America (premiering in 1982). Like Disney they were pioneers working in a standards vacuum, but they set a new bar for nature fakery. Perkins was forever having his young assistants lasso and wrestle terrified tame animals to “rescue” them. “They were totally ruthless,” Wyoming cinematographer Wolfgang Bayer told the Denver Post. “They would throw a mountain lion into a river and film it going over a waterfall.”Wild Kingdom still airs on Animal Planet. Stouffer was no less brazen. In 1995—after he was fined $300,000 for cutting an illegal trail through the property of the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies to his illegal hunting camp on Forest Service land—his staffers began opening up to the press, reporting, for example, that he staged fatal confrontations between predators and prey. In his film Dangerous Encounters, a cougar is shown “attacking” a cross-country skier. It’s a playful pet roughhousing with its owner. Stouffer is still cashing in on Wild America episodes and Dangerous Encounters through Amazon.com and other outlets.

“With photos you can include notes, but it’s hard to interrupt a movie,” observes respected wildlife-film maker Chris Palmer. For the National Wildlife Federation’s 1997 IMAX film Wolves,he rented models from Animals of Montana. “Sections of this film were made possible by employing captive wolves,” reads one of the credit lines. That was more than most filmmakers were doing 13 years ago, but like photo credits, movie credits often go unread. Palmer now uses that “mistake” as a teachable moment in his lectures and in his book Shooting in the Wild, to be published in May by Sierra Club Books. “Since then I’ve learned about game farms,” he told me. “Animals are kept in small cages and lead miserable lives. And they’re placed in even smaller cages and taken on the road for days to some wild place.”

Audubon’s design director, Kevin Fisher, has “no doubt we’ve unknowingly run game-farm photos in the past.” The staff knows of at least one mistake—an Animals of Montana cougar in the November-December 2009 issue. They figured it out at the last minute but didn’t have time to replace it. “We are definitely more vigilant now,” says photo editor Kim Hubbard.

Such errors are even easier to make when one deals with photo stock agencies. I saw an image of a game-farm cougar on the National Geographic site and asked if it was wild. They didn’t “have that information.” Animals Animals/Earth Scenes, Getty Images, and Corbis Images—all teeming with game-farm animals—said they had no way of telling if they were captive or wild. NHPA wildlife and nature stock photography labels some but not all captive shots. The only agency I could find that seemed conscientious was Minden Pictures. I clicked on an image of a cougar, and 17 “key words” came up, one of which was “captive.” But no information was offered for another cougar. With Minden’s help I later discovered it had been shot at Wild Bunch Ranch game farm in Idaho.

There is, however, some gray in the debate about captive-wildlife images. This from genuine wildlife photographer Joel Sartore: “People aren’t getting off their couches and seeing wildlife in the flesh anymore. So game farms can provide an appreciation of how majestic these animals are.” And game-farm advocates have a good point when they argue that too many photographers in the wild can stress wildlife and habituate it to humans. Still, I can’t think that if facilities like Triple D and its posh guest house were to vanish, their clientele would rush into the wild to squat for months in snow, sleet, and rain.

Where there’s no gray is in the need for honesty. In this regard there’s been dramatic progress in wildlife documentaries such as the BBC’s Planet Earth series, the new Disney films, material on the Discovery Channel, and PBS’sNature. These days there is little that I (or anyone) can positively identify as nature fakery or animal abuse.

All the big magazines devoted in whole or part to wildlife are now wrestling with how best to do the right thing. Audubon will not knowingly publish game-farm shots, and will clearly indicate in captions when animals are photographed in captivity (or in credits in rare situations where captions aren’t possible). Sierra tries to avoid captive shots, but when it does run them it labels them in the credits. Natural History uses few captive photos and includes the information in the story or captions. Smithsonian runs few and labels them in the gutter credit line. It won’t publish game-farm shots. Two years ago, after taking heavy flak for nature fakery, Defenders of Wildlifedecided to severely limit the number of captive images it runs in its magazine and calendars. “It struck me how hypocritical it was for an organization like Defenders to support operations that breed animals only so photographers can make pictures,” says photo editor Charles Kogod. National Geographic won’t knowingly publish game-farm photos, and when it runs a captive shot it’s identified as such and is almost always an animal used for article-related research.

National Wildlife, a booming market for game-farm photos until about 10 years ago, now uses none, though it does publish the odd shot of a zoo or rehab animal, reporting origin in the caption or credit. Genuine wildlife photographer and ardent game-farm critic Tom Mangelsen used to tease National Wildlife photo director John Nuhn by telling him he should change the name of his magazine to National Game Farm.Nuhn got the message and not just from Mangelsen. “I was getting tigers running along beaches in Santa Barbara, mountain lions in perfect positions on red rocks in Utah,” he says. “I figured these are more than just captives; these guys are being trucked.”

But nature magazines are dwarfed by other markets, few of which know or care about the source of animal photos. Most magazines and virtually all publishers of posters and calendars, even those commissioned by environmental organizations, have no standard for honesty in wildlife photography. The vast hook-and-bullet press is shameless. Battery acid is splashed on captive fish to make them leap frantically. I talked to one genuine wildlife photographer who has quit submitting deer photos to hook-and-bullet publications because he can’t compete with all the photographers who rent or own penned deer bred for freakishly large antlers. One such mutation, appearing on the covers of countless hunting rags, had four owners, the last of which bought him for $150,000. For years the ancient beast was kept on life support with medications and surgeries.

One might suppose that Outdoor Photographer magazine would have strict standards. But no, it advertises game farms and instructional safaris to the scenic destinations to which game-farm animals are trucked. In November 2009 it ran a half-page photo of a timber wolf in “rural Montana” that “suddenly strayed from the pack” to sniff the camera and tripod of a photographer. This was an untruth; rural Montana wolves don’t behave this way, and there was no pack. I emailed the photographer and asked him at what game farm he’d taken the shot. “Animals of Montana,” he proudly replied. One might also suppose that NANPA would have strict standards. But no. It advertises game farms, distributes game-farm promos to members, even sells its membership list to game farms.

There is, however, a rapidly growing countermovement called the International League of Conservation Photographers. ILCP director Cristina Mittermeier offers this: “There are no standards for the care of game-farm animals. They’re rented out for profit. I find that sickening. We don’t even know how many game farms there are. They give nothing back to habitat conservation.” The ILCP is working with the American Standards Association and a standards expert from the EPA to bring decency to game-farm photography by setting up an advisory group to establish guidelines. Advisers will include representatives from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the photographic community, and the game farms themselves.

If there was ever a need for game farms, it has diminished, especially with the advent of autofocus lenses and super-fast pixel imaging. From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, Sharon Cohen-Powers, now president of NANPA, ran a photo stock house called The Wildlife Collection. “Back then getting a sharp image of a bird in flight was a miracle,” she says. “And there were the baby shots—if you didn’t have them, you didn’t make the sale. It was like, ‘Please go out and shoot at game farms.’ And it wasn’t long until you started saying, ‘Stop shooting at game farms. I don’t want these shots anymore—they’re all the same.’ ”

The intrusion on and habituation of wildlife that game farms are said to prevent has been reduced by remote, motion-sensing camera traps. Even 15 years ago Joel Sartore was using this technology to photograph Florida panthers—among the rarest of cats. Steve Winter braved temperatures of 30 below zero in northern India to get the camera-trap shots of wild snow leopards that appeared in the June 2008 National Geographic. And for his stunning coffee-table book Great Plains (University of Chicago Press), Michael Forsberg invested close to four years and many 1,200-mile commutes to get camera-trap photos of wild cougars in South Dakota’s Black Hills. They’re nearly as sharp as the fakes Geiger and I procured in two hours.

When game-farm advocates claim it’s “impossible” to photograph subjects like wild Florida panthers, cougars, and snow leopards, what they really mean is that they don’t care to suffer the necessary discomfort and spend the necessary time, effort, and money. Even without competition from game-farm patrons, genuine wildlife photographers struggle to make a living; with that competition some have to find new work. That’s unfair.

But my biggest gripe with captive-wildlife photography is its dishonesty. The spectacular Winged Migration, released in 2001 by Sony Picture Classics, turned on the nation to the beauty of and threats to the avian world. But the film didn’t get around to informing viewers that some birds were tame, raised from eggs, and imprinted to their handlers. Did the end justify the means? I’d argue no.

Condemning untruthfulness in all media, Sir David Attenborough, standard-bearer for ethics in wildlife filmmaking, declared: “You can lie in print; you can lie on film; you can lie on radio.” But when the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Cruel Camera confronted him about a scene supposedly shot under snow in the Arctic in which a polar bear gives birth, he admitted that it was shot in a zoo.

Why are lies anathema in all journalism save photo journalism? If a picture is worth a thousand words, is not a film, book, magazine, calendar, or poster containing photographic lies as objectionable as, say, a “news story” inThe New York Times by Jayson Blair. Blair, you may recall, was the fiction writer who masqueraded as a reporter. When the Times learned he’d concocted scenes, sources, and quotes, it fired him along with the paper’s unwitting executive editor, Howell Raines. Even “full disclosure” couldn’t get that kind of reporting sold or read much beyond supermarket checkout counters.